“we have no power or wifi/internet”

“we still have power but no water”

“still no power also, using the car as a heater and to charge my phone”

“no power but doing okay”

“keep an eye out for a boil water notice”

“are there any gas stations in Brownsville without a 2 mile line?”

Text messages from my coworkers were flying around on a group thread. A polar vortex had just rocked the state of Texas, plunging it into one of its longest and coldest deep freezes, unlike anything most Texans had ever encountered. I grew up in the Canadian province of Prince Edward Island, where we considered Toronto to be balmy in comparison to the icy winds and high snowdrifts that inclement weather inflicted on us. I was used to hunkering down, bundling up. I knew what to do if and when the power went out. Down in Rio Grande Valley in Texas, where I have been living since last year, residents are always prepared for hurricane season, but they were not prepared for the havoc the freezing temperatures wreaked in mid February 2021. Even more devastating, the state’s electrical grid overloaded because of increased demand, leading to massive outages. Freezing homes, burst pipes, and widespread anxiety settled in as people rushed to fill their gas tanks, warm up in their cars, and stock up on essential items.

I learned that on South Padre Island, a barrier island along the Texas Gulf Coast about an hour-and-a-half drive from my home in McAllen, around five thousand green turtles—among the largest of sea turtles—had been rescued from the frigid water. These endangered reptiles are at risk of being cold-stunned in temperatures below fifty degrees Fahrenheit, rendering them paralyzed but conscious. Local volunteers, many of whom had no power or water in their homes at the time, showed up to load up as many turtles as they could in their cars to transport them to a nearby convention centre to warm up for several days.

The polar vortex historically has circulated around Earth’s poles, occasionally sending its frigid air south. Human-caused climate change is accelerating this phenomenon at an alarming rate, and meteorologists predict that it may soon become an annual event. Until now, Texans haven’t needed to be prepared for a cold snap of that magnitude. As more and more people around the world experience on a regular basis the severe and often devastating effects of climate change, how do we find our place in the climate-change conversation? How do we cope with an emergency slowly unfolding all around us?

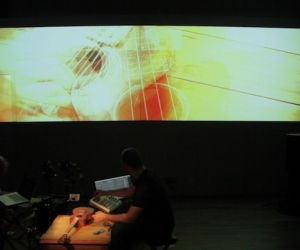

This issue introduces readers to artists who are bringing their unique perspectives to understanding ecological loss and exploring the environmental and emotional impact in their creative work. I am struck by how a concept that still feels tremendously abstract to many of us can be made both tangible and personal. Readers will discover this in Tanya Kalmanovitch’s polyphonic exploration of her hometown Fort McMurray (Tar Sands Songbook), Matthew Burtner’s compositions incorporating recordings of melting Alaskan glaciers, and Lou Sheppard’s exploration of the ghosts of rivers, to mention just three of such artists in this section.