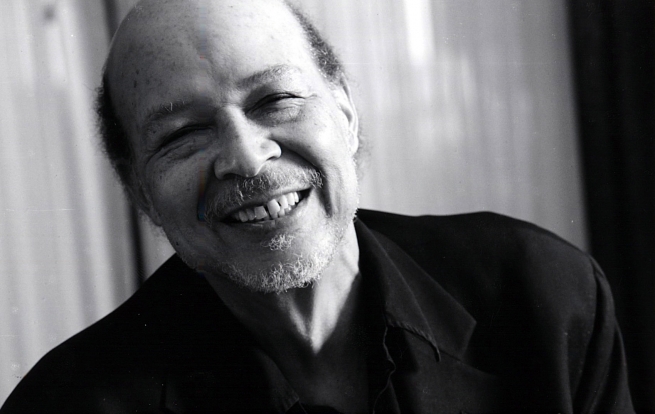

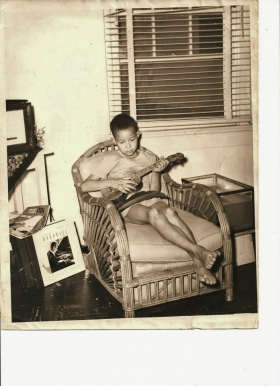

Born in Harlem and raised in Hawaii to a father from Louisiana and an opera-singer mother from Ohio, Burrell was exposed to a rich and unusual mix of music in his formative years. As a teenager in Hawaii he led an r’n’b band, but there was something else in the Pacific air that would come forth in one of his greatest but least known—or least understood—achievements. Having arranged Puccini and Leonard Bernstein’s West Side Story for small jazz combos, Burrell in 1978 began work on his own jazz opera, Windward Passages, largely based on his own time in Hawaii. The opera barely saw production but the forty-one songs it comprised would become staples of his recording and performing career.

For the last five years, Burrell has been working on what should be seen as his second major work. Through an open-ended residency with the Rosenbach Museum and Library in Philadelphia, the city he has long called home, Burrell and his wife and librettist Monika Larsson have been researching the years of the American Civil War, and have composed five hours of lyric and instrumental music about the five years that nearly tore the states apart. Research for American Civil War: 1861–1865 has taken Burrell and Larsson deep into the lives of nineteenth-century servicemen and civilians, and deep into the art of storytelling as well. With access to the Rosenbach Library’s vast collection of historical letters and documents, the couple had to consider what stories they wanted to tell and what sympathies they wanted to give voice to.

“What side of the story are we going to write about?” By way of explanation, Burrell says, “Up until the time the Emancipation Proclamation was passed, it seemed this country was embarrassing its allies by not letting go of slavery. Mexico had done it, the U.K. had done it.”

The stories and songs have often ended up being about the costs of war, about a young man heading off to enlist and disappearing, or about a boy forgoing dinner so his younger sister can eat. They are, in short, songs more of sadness than anger. The works have been presented in annual concerts at the Rosenbach in Philadelphia’s historic Rittenhouse Square, in a small room that seats about thirty. The final chapter, “Homage to the Martyr,” was presented in April 2015. Burrell and Larsson now face the task of deciding what to do with it.

So far, the works have all been presented either as solos or duets, featuring Burrell at the piano with either trombone, violin, or voice. The trombone duo—Turning Point, focusing on 1863 (the Emancipation Proclamation, the Battle of Vicksburg, and the Battle of Gettysburg)—is the only one to have been heard by many people outside the Rosenbach’s walls. Recorded with trombonist Steve Swell, that chapter, which is yet to have words set to it, made for an extraordinary release on the Lithuanian jazz label NoBusiness in 2014.

Burrell and Larsson are now grappling with how to move forward: whether to record the rest and how else to get the work to a larger public. “If we work on it for two more years, and we are ready to present it in other venues, and we have a small ensemble, I would consider it a finished work of two or three hours,” said Burrell, who is given to lengthy explanations, in an interview at the Rosenbach the afternoon of the presentation of the final part of the cycle in April 2015.

“Now we’re getting sophisticated,” Larsson added. “We don’t want it to go the way of Windward Passages.”

IF THE TITLE WINDWARD PASSAGES IS FAMILIAR AT ALL,

it’s most likely from the 1980 HatHut release that bears the name. That beautiful solo recital features eleven of the opera’s forty-one songs, displaying Burrell’s neo-ragtime attack: his fantastic reach, his remarkable assuredness, and his impressively strict time. But as with most of the available recordings from the songbook, there’s no singer involved, despite the work having originally been written for eight voices. More than a dozen commercial releases have included songs from the opera, not the least of which is the fantastic spate of records Burrell made as a member of David Murray’s quartet for the Japanese label DIW.

Burrell met the Swedish-born Larsson in 1978. She was living in Hawaii at the time, but he had already moved back to New York. “I was not at all in the same realm as Dave,” Larsson said, looking back. “I lived in Honolulu, I was married to a scientist, and I was writing poetry.” But Larsson soon moved to New York with Dave to work on an opera, as well as a relationship. Like the Civil War project, Windward Passages dealt with social issues, such as racism on the islands and resistance to statehood.

“We wrote this full-length opera, and Dave scored it for a twenty-two-person orchestra,” Larsson said. “We got funding, but the big money—we never went for it. Now we are looking into going back to it because of its sociopolitical importance.”

“Neither of us knew whether I could do it,” Burrell added, laughing.

An octet version with a single singer—and including trumpeter Marcus Belgrave, drummer Roy Brooks, and trombonist Curtis Fuller—was presented at the Rome Opera House in Italy. It was presented again, this time with the Black Actors Guild in Oakland, California in 1982.

And then, nothing.

“It dissipated (the opportunities) and we knew this would be good fodder for recordings instead,” Larsson said.

The fantastic recording sessions Murray’s quartet with Burrell, Fred Hopkins, and Ralph Peterson, Jr., made in 1988 resulted in a string of releases as strong as anything in either Burrell’s or Murray’s discography. Lovers, Deep River, Ballads, Spirituals, and Tenors were all released that year, featuring a half dozen different Windward Passages selections across them. The following year saw a new Murray quartet release Lucky Four, with three Windward Passages tunes, as well as Daybreak, an exceptional duo record by the pianist and the saxophonist. The two would continue to work together for several more years, and in 1993 released a record, also called Windward Passages, with Larsson reading her words on one track.

But to hear the Windward Passages songs with Larsson’s words, one must track down a copy of the 2010 Rai Trade release Dave Burrell Plays His Songs—Featuring Leena Conquest. While it’s still not the octet or the big band arrangements, and it’s far from the complete book, it’s the closest thing yet to a release of the work. Conquest—whose powerful singing might best be known from her work with William Parker (especially the wonderful 2002 release Raining on the Moon)—gives a present and articulate voice to Larsson’s verse.

Burrell and Larsson had neither the experience nor the resources to keep the Windward Passages project alive thirty years ago. They’re savvier now, however, and Burrell’s reputation has grown over the years, as has their collaboration. “It didn’t compare to what we’re doing now,” Burrell said. “My voicings . . . I didn’t want to be out of step with what was trending. I knew that I liked Ellington, Strayhorn, and Monk—in particular, on the piano. To swing and still have some grit and minor clashes was a whole different ballgame. It was a struggle to get to be heard and have recordings that were clearly defined.”

BURRELL MIGHT STILL BE BEST KNOWN AS A FREE player, but his songwriting and interest in ragtime has been gaining notice. In 2006, Burrell and writer and jazz scholar John Szwed appeared at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., in an onstage recreation of the 1938 Library of Congress recordings and interviews with Jelly Roll Morton. Since that time, he has been playing free improvisation and stride-influenced formality alongside one another.

“More recently they have been accepted in the same concert—the ragtime, and ease into free bop, and slowly easing into high energy and no tonality,” he said. “This idea came to me as a kid, that I don’t want to just play one way. I get bored.” All of which—the rag and stride, the contemporary dissonance and open improvisation, and perhaps most of all, a genuine love for historical research—have come together under the Civil War banner.

“Just playing jazz all over the world for decades has made it a lot easier to get this kind of fluidity that I didn’t have in David Murray’s octet,” Burrell added. “I wouldn’t say I’ve mastered the piano but I’ve come a long way towards the mastery I was seeking.”