Last year, pianist Cheryl Duvall and violinist Ilana Waniuk joined the circus. This did not involve playing instruments while hanging from a trapeze, but like many big-top acts, it did require a certain amount of risk.

Duvall and Waniuk are the artistic directors of Thin Edge New Music Collective, a Toronto chamber ensemble that has commissioned dozens of composers, most of them born after 1980. Through its adventurous and smartly programmed concert seasons (six so far) and its penchant for popping up at nonclassical events, Thin Edge (as it’s familiarly known) has become a welcoming exploratory-music hub for local artists and audiences. Residencies at the Banff Centre and in Italy and Switzerland, tours in Canada, and a performance visit to Argentina have allowed Duvall and Waniuk to share that vibe with musicians and composers outside their hometown.

A Thin Edge concert often feels like a happening. You hear turntable sounds in the mix. You suddenly feel like you are in the middle of a flash mob. Maybe you see slow-dancing fire and large swinging rocks. All these things were part of Balancing On The Edge, which united contemporary classical music and circus arts in a provocative, thrilling, and thought-provoking exploration of the concept of balance as it applies to modern humanity. The forty-person production, which premiered at the Habourfront Centre’s NextStep series in Toronto in November 2016, was conceived and developed by Thin Edge’s Duvall and Waniuk and aerialist and choreographer Rebecca Leonard, who runs A Girl In The Sky Productions. “Magma,” the show opener, featured Nicole Lizée’s “Phonographenlieder” (2014) for string quartet, piano, percussion, mezzo soprano and turntablist. Circus artists Diana Lopez and Rebecca Carney [SEE PHOTO BELOW] used flame torches and rocks suspended from ropes in their choreography. Three numbers were propelled by the music of renowned twentieth-century composers John Cale, Iannis Xenakis, and David Lang, the other three by recent works from Lizée, Scott Rubin, and Nick Storring. Both evening shows were sold out.

“It was the hardest thing we’ve ever done,” Waniuk says of Balancing on The Edge.

“It was,” Duvall agrees. “And the biggest, the most personal, and most complicated in terms of technical things.”

We are sitting with empty coffee cups in the noisy café of Artscape Youngplace, a bustling arts and culture building in Toronto’s west end, on a bright December morning. Our interview has hit hour three. We’re on a roll. I am now used to Waniuk and Duvall finishing each other’s sentences, and the frequent fact-checking of performance info as they scroll down the Thin Edge Web site on their smartphones. They are good company.

In October, I’d seen workshop versions of two Balancing numbers during Toronto’s Nuit Blanche festival. I saw the full show with my nine-year-old daughter at a student matinee held the day of the world premiere. We loved it. But that afternoon, I learned weeks later, the directors still did not know if the appeal they had launched with the local arts council, which had rejected their last grant application, would be successful. They’d received music grants, but their many applications for theatre and interarts grants had all been rejected, despite positive feedback. They were seriously on the edge.

“Circus is going through a redefinition of its identity,” Leonard later tells me in a phone interview. (After 146 years, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus is closing its big top forever in May 2017.) “Circus is moving away from the spectacle entertainment form. Everybody knows of Cirque du Soleil. Reinvented the art form. Harbourfront has always supported boundary-pushing production, but there is not a large presenting network for circus arts in Canada. It’s just starting to be recognized.

“Now we’re seeing circus arts as a discipline for expressing ideas, and for social commentary. It’s becoming an arts practice like contemporary dance or music.”

TWO GIRLS ON AN ANCHOR

The plates started spinning, so to speak, a few years ago when Cheryl Duvall attended the Contemporary Circus Arts Festival of Toronto, which Rebecca Leonard coproduces with aerial choreographer and Anandam Dancetheatre artistic director Brandy Leary. “The circus I had seen in the past was like Ringling Bros., whereas what I witnessed at that event was very fringy and emotional,” Duvall recalls. “There were six different acts and each one was different and incredible. I could tell they were exploring deep things. I remember there were two girls on an anchor. There were lights and beautiful music. I thought, Why isn’t this more popular around the city?

“The steps Thin Edge was taking then were moving away from traditional—we were taking risks. So I thought, Oh my god, we have to do something together.”

Leonard, who had recently attended a Thin Edge fundraiser, felt that the ensemble’s ethos was in line with her creative work. “We were all pushing the envelope, and on the fringes of what the general public knows about our art forms,” she says.

The scope and the shape of Balancing On The Edge started to gel when they were working on grant applications. Meetings, sometimes over a bottle of wine, involved lots of talking and listening to music. Duvall and Waniuk would play for Leonard music that was unlike anything she’d heard before, and talk about its meaning; she would share her own impressions of the music, and talk about about circus disciplines and apparatus. Early on, they knew that creators from their two arts should be brought actively together. “I invited artists I thought would be stimulated by certain works of music,” Leonard says. “Some were asked to work in specific disciplines, some were paired together. It was important to give them artistic ownership, because these pieces were personal—we were asking them to draw on stories from their own experiences of balancing on the edge.”

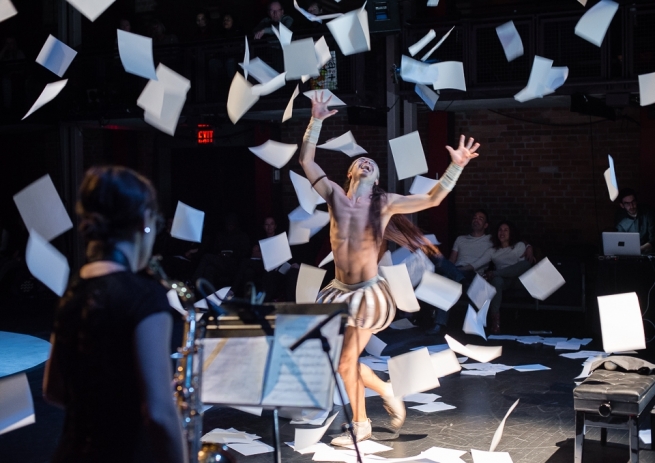

They wanted the show to feature pieces that were built from scratch, Waniuk says: “Something created by the composer and choreographer (most often also the performer). So it would be a joint process, the music not just in the background.” Two of the six compositions used in Balancing were commissions. Nick Storring’s “Amanhã” (for piano, percussion, saxophone, cello, two violins) was created for Brandy Leary’s solo piece Excavating Meaning, and Scott Rubin’s “Naked To The Sky” (piano, percussion, saxophone, violin, motion-sensitive live electronics) for choreographer Emmanual Cyr’s piece of the same title, which was performed by Louis Barbier [SEE PHOTO BELOW] at Harbourfront. Both compositions were developed through an ongoing “conversation” between the creators of the music and the movement.

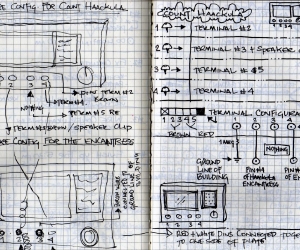

The main focus of the wider practice of composer and improvising violist Rubin is an exploration of the relationship between sound and movement. Currently a Ph.D. student at the University of California at Berkeley and researcher at its Center for New Music and Audio Technologies, Rubin received his masters from McGill, where he also worked as a composer for music-cognition experiments. While in Montreal, he founded a week-long workshop that focuses on the creation of new music through collaboration between performers and composers. “What I struggled with most was the basic notion of merging contemporary circus and contemporary music,” Rubin writes in a short Q&A published on Thin Edge’s Facebook page. “I wanted to create responsive environments where the musicians play off Louis (the circus artist) and vice versa. I wanted the sphere of influence of the performers to be ambiguous, for them to be on the edge of their performative roles, not to simply put fixed choreography on top of fixed music.” In the twelve-minute piece, all the performers become a “single interdirected multidimensional force,” by way of digital and analog connections and cues. Notation was a big challenge: “When composers write music on paper, they must account for the (in)flexibility of their notation and for what constitutes something as ‘correct.’”

Paper was used to great effect in Cyr’s choreography, and undoubtedly had symbolic significance, even to those unaware of Rubin’s struggles. A third of the way through the Habourfront performance, the musicians shifted from a tentative mood—evoked by sustained notes, pauses, short flourishes—to frenetic playing that conveyed a more chaotic vibe. At the same time, Barbier—in mad-king getup, consisting of a paper crown, skeletal renaissance-style pumpkin breeches, white shoes, and strips of thin white cloth wrapped around his wrists—grabbed pages from the music stands of Waniuk and saxophonist Chelsea Shanoff and tossed them high into the air. Sheets of paper were “released” from the top balcony, followed by a light sprinkling of scrunched paper balls. This surprising, darkly humourous, and dramatic section of the piece suggested—to me, at least—the emotional state of a leader or creator character being overwhelmed by ideas, work, people, responsibilities, etc. Barbier then used the paper in a sequence involving contact juggling, his more exploratory and focused mode reflected in the musicians’ playing.

On Rubin’s Web site there’s a video of a Balancing On The Edge performance, as well as a December 2016 one by Eco Ensemble and dance artist SanSan Kwan in Berkeley, California. Watching the videos, one after the other, you see how the piece can work in both a theatre and traditional concert hall. Duvall and Waniuk want Thin Edge commissions to have lives after their first performances, and are always game to get down to the nitty-gritty to make sure that happens. In July 2016, they spent a week working with Shanoff, Thin Edge percussionist Nathan Petitpas, and Rubin at the Avaloch Farm New Music Institute in New Hampshire, exploring improvisation, playing techniques, and notation methods. “The residency was amazing and also really necessary,” says Waniuk. “Scott tweaked and changed things. He would say, ‘I want to make this sound or that sound,’ and we would figure how to achieve it. He spent a lot of time with Cheryl inside the piano, and creating funny sounds for the drums.”

“After he gave us our initial score, we each had meetings with him privately,” Duvall chimes in. “And we would say things like, ‘You wrote it in that way, but this might be a clearer and more concise way to do it.’ So we informed his notation a little bit, had some say in how he was going to communicate the score to other musicians in the future.”

GETTING PERSONAL

Duvall and Waniuk’s passion for working closely with composers is rooted in the early days of their friendship. They met as undergraduates in Wilfred Laurier University’s faculty of music, where they were frequently paired for duo pieces. “Laurier has a very rich composition program, with people like Linda Catlin Smith and Peter Hatch,” Duvall says. “Around my third year, Ilana’s fourth, every other Wednesday there would be a composer show, and we played almost every one for a couple of years.”

The Penderecki String Quartet, in residence at Laurier since 1991, made a strong impression on Waniuk: “Every chamber class, they devoted the same attention to new music as they would to Haydn. I’ve been other places where that kind of attention or care was not taken. It was great having that instilled from the beginning. Of course, there is a canon—when you study a traditional instrument that’s hard to escape—but it is evolving constantly, and what is happening now is equally valid.”

Duvall received valuable insights when she was trying to learn new pieces that were, essentially, not playable. “I used to be this hyper-perfectionist, and would try to play every single note perfectly, no matter what,” she laughs. “And so I had to learn how to talk to composers, and say, ‘Look I can’t do it,” and not feel ashamed about it.

“To do that was great, because the reaction would often be, ‘Oh, I just went to my mini keyboard and went like this (she slaps her hands rapidly on the café table several times) and notated it.’ So we’d talk it through, and I’d say, ‘Why don’t you draw a block instead of writing every single note and accidental?’ Or someone would say, ‘Oh I wrote it on the guitar, I didn’t try it on the piano,’ or conceive things inside the piano that were actually impossible to do.

“Those are the kinds of discussions I would have—and through those, you get little glimpses into the concepts or the emotions the composers want in the music, too.”

Another influential experience for both musicians was intersecting with Laurier’s vibrant improvisation scene. “Kyle Brenders was there, and Brandon Valdivia, and there was an improvisation concert ensemble, which still exists,” Waniuk recalls. “It was an introduction to open scores and graphic notation, and that way of thinking about things—I found that inspiring.”

[ABOVE Members of Thin Edge New Music Collective performing at Balancing On The Edge, 2017]

DECK THE HALLS

Around Christmas 2010, Waniuk and Duvall started talking about how they both wanted to play twentieth-century music and “really, really new music.” Soon they were looking around for other musicians who shared their passion for not only playing the music, but also presenting it in unusual venues and thematic contexts that would allow it “to comment and reflect on modern society,” as declared on the Thin Edge Web site.

“We were very ambitious right from the beginning,” Waniuk says of Thin Edge’s first season (2011–12), which saw the pair work with oboist Elizabeth Eccleston and percussionist Olaf Szeste in the core ensemble, and also guest musicians. Their second concert, An Evening of Firsts, was presented in Toronto, Waterloo, and Ottawa and featured new works (most commissions) by Canadians Margaret Ashburner, Aura Giles, Tova Kardonne, August Murphy-King, and Nick Storring.

“We knew about commissioning but not presenting grants (yet). We said to the composers, well you can write for whatever percussion you want, we don’t want to hinder your creativity,” Waniuk says, smiling and rolling her eyes.

“We did say that?” Duvall laughs.

“Yup. So we ended up paying out of our pockets for everything.”

“Oh my god. We thought we could rent a venue and the tickets sales would pay for the venue and pay everybody a fee!”

“Even things like rehearsal space—you come directly from school, where you have access to things like a percussion studio, and suddenly you realize you don’t have that anymore.”

“We jumped into the deep end and learned to tread water!”

Toronto composer, improvisor, and violist Kardonne, one of thirty female composers Thin Edge has commissioned, helped secure Duvall and Waniuk’s first workshop experience at the Banff Centre in early 2012. “It was the first time we got to work on a piece from the beginning,” Waniuk says. “She would bring us sketches, and we would work on them together. By the end of our ten days, we’d put together part of the piece (‘Some Pubescent Notions of Group Dynamics’).” At Banff, Kardonne suggested Thin Edge, as in “thin edge of the wedge,” as a name for Duvall and Waniuk’s new ensemble. To the two friends, the two words suggested something small that would grow into something much bigger. That process began before they even left Banff. They befriended German accordionist Olivia Steimel and Montreal flautist and composer Solomiya Moroz, and a year later collaborated with them on a major tour, Keys, Wind and Strings (KWS), a program featuring commissioned works for the quartet by Anna Pidgorna and Moroz.

The final concert of Thin Edge’s ambitious third season was its annual Premieres showcase. Among the six works were Monica Pearce’s “cognitive dissonance” for violin, piano and Oxblood (“a very cool electroacoustic instrument of amplified springs invented by Anthony T. Marasco,” says Waniuk), new pieces by Hiroki Tsurumoto, Christopher Reiche, and Adam Scime (that season the ensemble played in the workshop presentation of Scime’s electroacoustic opera l’homme et le ciel, written with librettist Ian Koiter), and British composer Sophie Pope’s “O-boe-Ya,” the first piece commissioned through the Thin Edge Commissioning Fund, a community engagement initiative.

“In the beginning, often we could only pay honourariums to composers—if we were unable to get a grant,” says Waniuk. “There are so many composers we want to work with, but it’s hard to find funds, as we’re a small organization. It’s a way for people in the new-music community to feel more involved.”

STRENGTH IN NUMBERS

Over its six seasons, Thin Edge has grown from a core group of four (violin, piano, oboe, and percussion) to a flexible ensemble of around a dozen core and affiliate members, presenting from three to five programs of new music each season, often featuring guest artists and ensembles or collaborating with them. “We have an amazing crew of performers who are willing to do a lot,” Waniuk says.

“They go on the rides of our crazy ideas,” Duvall adds. “They’re all risk-takers, which is awesome.”

In early 2017, Thin Edge completed its second Canadian tour as one half of Raging Against The Machine, a double-sextet project with Montreal’s Ensemble Paramirabo. “The concept comes from when we were a young ensemble and finding it hard to break in to get funding, and when we would get funding it would be peanuts, and we were stretching every dollar,” Duvall says. Paramirabo artistic director and flautist Jeffrey Stonehouse had attended a couple of Thin Edge concerts, and the Montreal ensemble played the Music Gallery in Toronto. The two groups soon wanted to be more than friends. “The concept is to play music together, and showcase each ensemble,” Duvall says. “An important aspect of that collaboration is sharing knowledge and our stages in each other’s cities.” Raging Against The Machine’s recently released, self-titled debut on Vancouver’s Redshift Records captures its 2015 performance program, which includes works written for the respective ensembles by Anna Höstman (Toronto) and Patrick Giguère (Montreal), and Toronto composer Brian Harman’s piece for the double sextet. The 2017 program included new pieces by Colin Labadie and Anna Pidgorna. Raging has also commissioned Nicole Lizée. “Her piece pits the groups against each other and she’s coding a video game that is somehow interactive,” Duvall reveals. The tentative title is “Chamber Kill.”

Ask someone if they know a circus tune and they’ll likely start whoot-doot-dooting “Thunder and Blazes,” the title given to Canadian composer Louise-Philippe Laurendeau’s iconic 1901 band arrangement of Czech composer Julius Fučík’s 1897 military march “Entrance of the Gladiators.” The boisterous piece will outlast the traditional circus, which has been retreating to the history books for some time now.

With Balancing On The Edge, their brand new joint production company, Duvall, Waniuk, and Leonard [SEE RIGHT PHOTO] are committing to the future of circus. And they have reason to feel good about it. Fifteen minutes before the opening performance at Harbourfront, they found out that they had not only won their appeal, but would also receive triple the amount they’d requested from the arts council.

“It was such a powerful experience for me and you—going through all that,” Duvall says, turning to Waniuk. “When we all met the other day to open our first bank account, we got into a flurry of discussion about the exciting ideas we have for the future of it. It’s such an undertaking: there’s so much responsibility.”

“People really liked the pieces in the show that were built from the ground up,” Waniuk says. “They build strong relationships from the beginning, and you feed off that creative energy the whole time.”

“You know how hard it is to work with people in general. For something like this, you need to have a good feeling about it.”

“You need a certain amount of gut instinct.”

FYI, MAY 2017: Thin Edge New Music Collective’s Keys, Winds, and Strings is a two-concert festival at with special guests German accordionist Olivia Steimel and flautist and composer Solomiya Moroz. May 24: Works by Allison Cameron, Gregory Lee Newsome, Uroš Rojko, Paul Clift, Solomiya Moroz and Marielle Groven. May 25: world premieres of works by Jason Doell, Germaine Liu, Fjóla Evans , Kasia Czarski-Jachimovicz, and Tobias Eduard Schick. Both concerts 8 p.m., Array Space, Toronto.

AUDIO: Linen (2014) by Anna Höstman, performed by Thin Edge New Music Collective. Recorded in concert at Gallery 345, Toronto, in February 2014.

PHOTOS: Home page slide, top portrait, and photography from Balancing On The Edge (November 2016 at Harboufront, Toronto) by Kevin Jones.