Admirers of Giorgio Magnanensi—composer, conductor, teacher, and the artistic director of Vancouver New Music Society—tend to be lavish in their praise of him. “Giorgio is singularly the best conductor of modern music, period,” says composer and Capilano University jazz instructor Bradshaw Pack. Vancouver music critic Alex Varty calls him “one of the most outgoing, provocative, and multifaceted musicians on the local scene.” And music scholar David Gordon Duke writes that he has “an exhaustive knowledge of the international scene, yet his strong identification with—and enthusiasm for—more North American ideas, gives him the broadest of perspectives.”

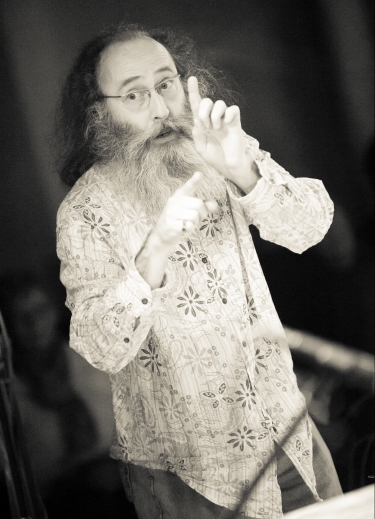

But if you had been among the dozen or so audience members at Magnanensi’s performance at the Roberts Creek Arts Festival this past spring, you may have imagined that you were hearing the lacerating cacophony of an angry, rock-wielding child attacking a blackboard, amplified into bucking feedback. Hunched in the back corner of the home studio where the show occurred, a mad-scientist-like figure complemented this savagery with some alarming behaviour aimed at his laptop, including waving a flaming lighter at it. A halo of Einstein-like grey hair and an unruly beard shrouded furrows of concentration and, occasionally when the screen went blank, bewilderment. Granted, the performance wasn’t so much about the music as it was about watching sound: the focus was not Magnanensi but rather the large screen at the front of the room projecting an array of geometric and psychedelic images created by the sound. Or was the imagery creating the sound? In any case, our eyeballs were listening.

Part of an annual alternative-arts festival set in the artsy, ferry-commute town of Roberts Creek, B.C., where Magnanensi lives with his artist wife and two sons, the strange spectacle was part of the musician’s continuing exploration of what happens when you try to translate sound into light. The project allows him to manipulate the abstract patterns generated by sounds, through the layering of effects such as delay and phase-shifting, to produce moving art that’s sonically synesthetic. Magnanensi calls this work “theatre for the ears.”

Picturing sound is just one of the offbeat, investigative concerns of the fifty-three-year-old musician. As part of a trenchant vision to foster new ways of thinking about sound, new ways of listening, and especially to engage the community in creative activity, Magnanensi has initiated scores of workshops, performances, and public projects, none of which result in the kind of music most of us are attuned to. With Vancouver New Music, for example, he launched the free, ongoing series Soundwalks, which invites participants to open their ears to the acoustics of the natural environment. He produced a four-day Circuit Bending Cabaret (2012) for which participants young and old rewired various sound-producing children’s toys for a toy-symphony performance (“a delightful, thought-provoking, and very weird experience,” confirmed one blogger). The Complaints Choir, founded in 2008, invites all to kvetch in unison. Among the dozens and dozens of international performers he’s invited to perform in Vancouver, one of the more memorable was young Japanese musician Atsuhiro Ito, who plays a sound and coloured light-producing neon light bulb with virtuosic skill.

But for all this unfettered pioneering on the sonic fringe, Magnanensi’s early career was steeped in tradition. He was subject to a highly formal conservatory education that led to an esteemed early career conducting opera and classical music ensembles throughout Europe. Born and raised in Italy, he studied composition and conducting, mostly in Rome, as well as in Paris and Salzburg. He taught counterpoint and harmony at conservatories in Italy, and lectured for two years at the Tokyo College of Music. He was principal conductor of a number of Italian chamber orchestras and ensembles, and served as guest conductor in Ireland, France, Japan, and Syria. His own compositions, which now number more than 100, have been performed throughout Europe, as well as in Canada, Japan, and the U.S. Along the way he has earned numerous awards, including first prize in the music competitions of the 1987 Zagreb Biennale and the 1988 European Biennale in Italy; in 1997 he received the Government of Canada Award.

“He’s a bit of a rare gem,” says his friend and collaborator Kedrick James, a spoken-word artist and University of British Columbia professor. “He stands out for me as a guy who has an incredible background understanding. He’s this odd blend of a really educated and experienced fellow, who has a totally revolutionary and distinct style. He’s incredibly open to the input that the newest amateur might bring—because it’s all meaningful and significant to him—and yet he is so well informed and deeply understanding of trends and historical practices in music.”

After nearly two decades pursuing a professional career in music from his base in Italy, Magnanensi found himself becoming less inspired with conducting and its “very hierarchical” dynamic between performers and conductor. “I am not a dictator. I don’t like to tell people what to do. It’s not a way of being together,” he says during a lengthy interview shortly after we met in Roberts Creek. Magnanensi is an affable gentleman. He speaks swiftly, intelligently, and broadly, constantly counterchecking his opinions and smoothly digressing into philosophical discourse: at one point, while discussing the concept of aesthetic judgment, he slips into an aside about whether what we see is reality or merely that which our retina transmits to neurons. Describing him in an email to me, his frequent musical collaborator Veda Hille writes that her Italian friend “is a ridiculously impassioned person. His enthusiasm and creativity appear to be boundless.”

In 1997, at the age of thirty-seven, following a brief visit to Vancouver two years earlier, Magnanensi won a Government of Canada fellowship for postdoctoral research in electronic music at Simon Fraser University. It was a brave move that entailed leaving his post at the prestigious State Conservatory of Music “Arrigo Boito” in Parma, Italy. But he was quick to make his way in Canada, gaining the esteem not just of Vancouver musicians but of musicians from coast to coast.

“I saw Canada as a very experimental place, as opposed to Italy, which was kind of dying in its own procrastination for any kind of change,” says Magnanensi.

Soon after his arrival, he was invited by the artist-run centre Western Front to participate in an improvisational music festival that encouraged all manner of unlikely mashups. The Italian conductor and classically trained pianist, now wielding an electronics kit, was paired with Huang Bich, a Vancouver-based virtuoso on the Vietnamese one-string dan bau.

At first, the two musicians found it challenging to meld their musical visions; at the time, both were still learning English. But soon enough, Magnanensi became inspired by the ancient instrument’s sound, abandoned his preconceived ideas and manipulated the music in subtle but novel ways. The performance was an unequivocal success for Magnanensi, confirming that his new country would open him to musical discoveries. “I kind of dived into a space where I embraced our difference,” says the artist, whose Italian accent still lingers. “It made me think I can play with everyone if I don’t get too stuck with my own ideas. It was really refreshing for me, and that value of difference has resonated with me for many years. The values I treasure most are sharing and the ability to understand difference, not as an obstacle but as something to embrace, as a path towards a deeper encounter. If we can explore that more and more, we can find ways of being together that are much more fulfilling for our own life, our own joy.”

Magnanensi started composing music, often with electroacoustic elements, for Canadian ensembles such as Standing Wave, Arraymusic, Aventa, Hard Rubber Orchestra, NOW Orchestra and, eventually, both large and small ensembles at Vancouver New Music. He also found himself conducting these works, as well as other composers’ music again. But his approach to new-music scores differs significantly from his classical-repertoire conducting style. Modern-music scores often offer alternative ways to read, relying on the interpretive creativity of the players—qualities that suit Magnanensi’s interest in a more democratic collaboration between composer, conductor, and musicians.

“Giorgio gets us really tuned to each other and then, in a sense, the score becomes secondary to the moment and to bringing out the creative potential of a group of individuals,” says James, who performed in one of Magnanensi’s most ambitious projects, Marginalia: Re-visioning Roy Kiyooka, a tribute to the late Canadian painter, poet, and multimedia artist, which received the $60,000 Alcan Performing Arts Award in 2007. “Working with Giorgio, you wind up thinking, Okay, I don’t actually need to be nervous about this particular thing. I need to learn to trust myself and my ability to communicate, and that’s how I’m going to really excel.”

I caught Magnanensi in action during the first rehearsal of his new composition Le feu et l’artifice, which Hard Rubber Orchestra performed for a standing-room-only audience at the Vancouver International Jazz Festival in late June. With passages of structured improvisation, dynamic swells, and furious rhythm, the piece is like a Jackson Pollock painting in big-band form. At times, it recalls some of Magnanensi’s favourite composers—Canadian Howard Bashaw, Italians Franco Donatoni, Luciano Berio and Giacinto Scelsi, and Greek new-music giant Iannis Xenakis.

After a round of friendly hugs and handshakes with the eighteen-member ensemble (four trumpets, four trombones, four saxophones, drums, Latin percussion, piano, electric violin, electric guitar and bass), conductor Magnanensi took the podium, thanked everyone, and said simply, “Let’s have some fun.”

One of the more physically expressive conductors, Magnanensi does not use a baton, so both hands can therefore circle, slice, jiggle, and otherwise sculpt the music into shape. Often his entire upper body surges and flutters in exquisite harmony with the sound. The British conductor Harry Bicket once compared conducting music to “trying to talk to somebody . . . without the use of language.” Magnanensi expands even this dialogue—as though simply conveying that the music is not enough: one must actually become the music. And in his soulful, intense body motion he nearly succeeds.

For the Hard Rubber Orchestra, bandleader John Korsrud told me, the composer had created a piece (Le feu et l’artifice) that enhances the best qualities of all the members. “He knows us well. He knows what he wants, and is very easy to follow. Everyone likes him. He’s one of the boys.”

The invitation to witness Magnanensi hone his work with the band was one of many open and generous gestures offered during our time together. He sent me numerous files brimming with sound clips of some of his twenty-three recorded or published works (for BMG, Earsay, and others) and nearly 120 compositions: a short, beautiful video of his latest experiments with visualizing music; a brief text by Milan Kundera on Xenakis, after I mentioned that I was a fan; and much more. And his Web site, a model of comprehensive documentation, offers hours—days even—of reading, viewing, and listening adventure.

“He’s kind of an eccentric maestro,” says James, marvelling at his friend’s highly organized approach to being a renegade. “He opens you up to the acoustic world that you didn’t hear before. I think all of his students would probably say the same thing: that they don’t hear the same way after they’ve spent time with him.”

At Vancouver Community College, where Magnanensi teaches improvisation, students encounter a friendly wizard of a professor, with a hippie vibe, who regards music as “a vehicle to share energy, to be in touch with people,” and its study an exploration of oneself. Technique? Not an impractical asset, but certainly not key to delivering powerful music . . . or energy, depending on how you look at it.

But let’s make one thing clear: “You can’t teach improvisation,” says the improvisation instructor. It’s a matter of playing with the students, and leading by conduction, the guiding technique that focuses on what’s happening in the moment between musicians. “It’s like being a spotlight to make players aware of other things running around, to which they can respond or not, because when you’re playing, you’re really concentrating on your own thing,” says Magnanensi. His students also read through scores that include improvised sections, and listen to recordings of improv ensembles. “You get them involved in thinking what it means to play without a score, to pay attention to how the material is forming in the present time, and to create musical forms to share in a large ensemble.” He says his role isn’t to teach how to play on a technical level—that’s the duty of the saxophone or guitar teacher. Rather, he strives to instigate exercises that reach beyond or even away from mechanical mastery and traditional interpretation—“everything that they can explore with their own imagination to extend the palette of their sound, enrich their voice as much as possible.”

“Beauty isn’t the parameters of the music, but the activity itself; the behaviour becomes beauty,” he tells his students.

“Why can’t we be aware of the possibility for sound to powerfully deliver energy that's not dictated by the knowledge of what it’s supposed to be?” he continues. “I think we should put aesthetic discourse aside —“Oh, this is beautiful; this is not beautiful”; then we are much more open and available to discover new things. I’m not against technique; the more you know, the more you can find in your own fingers or instrument, or your art. But there’s no specific thing that is needed. Everyone is different. The best musicians you can think of developed their own special technique: Charlie Parker, Frank Zappa, Pat Metheny.”

As our conversation about teaching music progresses, the thoughtful instructor touched on everything from the Cagean notion that everything is music to his own ardent belief that capitalism and creativity don’t jibe. Finally, I asked what he most hopes students will gain from his course. His answer speaks not just to his teaching philosophy but to his ideology in general. He hopes his students “learn about themselves, so that they can share that musically. Music,” he says, “can act as the agent for things that they value, because in music you kind of recreate a microcosm that represents the way you see the world.”

Audio: ... per essere fresco (2004). Composed by Giorgio Magnanensi. Performed by Silvia Mandolini, violin, and Brigitte Poulin, piano. Image: Giorgio Magnanensi. Image by: Aaron Sivertson <www.sightlinesphoto.ca>.