To many listeners, Ian William Craig’s debut LP, A Turn of Breath (Recital, 2014), seemed to materialize out of thin air—and not just because it was his first commercial release: one can hear almost spectral voices attempting to penetrate layers of electromagnetic detritus, like choral music trickling in from the spirit world. One can definitely hear the two main elements found in much of Craig’s recent work—his voice, which sits squarely in the countertenor register and demonstrates not only the resilience of training but also the vulnerability and character of individual exploration; and a battery of modified reel-to-reel tape machines, serving to both undermine and underline the humanity of his singing through their volatile processing.

Craig’s outward personality diverges radically from his music—similarly to many musicians, Morton Feldman most notoriously, because of his personal coarseness. But with Craig, it’s because his work is shadowy and elusive, whereas he himself is bright, animated, and downright funny. As he shows me around Vancouver’s Commercial Drive neighbourhood, he makes self-effacing wisecracks while greeting people he knows, and often erupts into thick gales of laughter. We find a spot at a local brewpub in an adjacent industrial area; barely two sips in and he’s off, full tilt. “My taste in music peaked when I was about two or three,” he claims. “My two favourite records were [Perrey and Kingsley’s] The In Sound From Way Out and [Mort Garson’s] Electronic Hair Pieces,” citing two of the Switched-On fad’s oddest documents. “It quickly spiralled into Aerosmith and Def Leppard. I had really bad taste in music all the way up until high school. I hear Steven Tyler, and I still get chills from what he can do vocally. I just love that cheesy, balls-out sentiment. It’s sort of like the Wagner of our times—distilled down into this one particular emotional intent, and they just keep on hitting it and hitting it.”

Cradle for the Wanting, Craig’s second album on Recital, may not approach Wagnerian grandeur or the cheese of his youth, but it does make great use of this deliberate belabouring of rarefied emotion. On his first album, tape loops were employed transparently to stack his vocals and shudders of noise, but here they often have a churning, iterative quality that is designed to bore through the music’s surface. Rather than opening outward, the music coils inwards.

Given Craig’s penchant for layering vocal tracks, it’s not surprising that one of his early catalysts was choral singing, which he began at age sixteen, parallel to his training in opera. “I took it to a particular point where I learned how to project and how to make it do enough of what I wanted to do. Once you start going down that path, your voice coalesces around a particular way of doing something. It’s definitely a way of being.” His love of popular music also deepened and broadened throughout his teen years, and he started writing his own songs. Even then, though, he preferred “vocal voyeurism” (as he calls it) over aesthetic monogamy. Indeed, beneath his trademark smears of noise you can hear him peering into various musical worlds—classical, popular, and others.

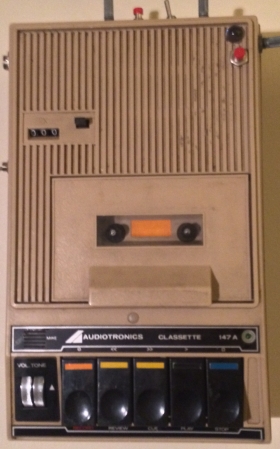

“[Music] is actually very printmakerly,” notes Craig, who is also a visual artist specializing in printmaking, who received his MFA from the University of Alberta. “It’s about working with these anachronistic machines and being very tactile with them and having a bodily communion with them. Randomness factors very heavily into it, which is a big part of printmaking.” John Cage’s work comes up as a crucial influence, helping Craig to surrender to this aleatory element and to think of sound composition differently. After graduating, Craig moved to Vancouver and, following a transitional period of experimentation, arrived at a set of bespoke tape-recorder-based processing systems. For the most part, the modifications he makes are reasonably simple: adding knobs that regulate the amount of electricity allotted to specific parts of the apparatus. Thus, the efficacy of these components becomes a parameter that he can reach out to and tweak. While the conventional wisdom of the digital era dictates that such modifications would be uniform between different makes and models of tape recorder, the results are alchemical and wildly unpredictable.

Any given tape machine has three heads: erase, record, and playback. The first two are the main targets of Craig’s circuit bending. Craig typically feeds the machines a tape loop, rather than using them for linear recording. Under such circumstances, if the erase head is switched off, prior signals are never erased from the tape, and new, incoming audio gets printed on top, over and over. At first, the sound is similar to digital looping, but as the tape reaches its saturation point, it stops responding the way it has. Recordings begin to cancel each other out, leaving strange residue behind, mysterious phantom resonances emerging from the séance of circuitry.

When Craig limits the amount of electricity the head receives (rather than cutting off its supply altogether), erasure perforates the sound more sporadically, leaving remnant trails. Fiddling with the record head, however, yields different results, because the electricity affects the magnetic accuracy of the recorded signal. Sonically, a less-than-accurate recording often means pinched-sounding timbre, but it’s never a totally sure bet.

Craig also discovered, by accident, a new, creative use for tape bias, which is effectively an inaudible sound, above the range of human hearing, that is recorded onto the tape as a sort of sonic primer. In some tape machines, the bias is linked to the circuitry around the tape-machine heads. On one occasion, after performing his usual surgery, Craig realized that something was amiss, even given the wide array of results his experiments had yielded so far: in addition to a pronounced muffled quality, the edges of each sound event seemed to crumble away. When the bias frequency is raised, lowered, or altogether eliminated, the tape only represents particular parts of the incoming signal’s frequency makeup. Additionally, it only responds to sounds of a certain amplitude. Evidence of his serendipitous discovery can be heard on the opening cut of A Turn of Breath, where the initial sonic image reveals itself pointillistically, dot by dot. Craig loops a length of tape over and over in order to make its iron-oxide coating flake off, leaving blotches of vacant audio. Sometimes he hastens this wear by sanding the surface himself. He’s also taken to more arbitrary circuit bending, yielding surprise echo circuits or even ad hoc tone generators.

For many listeners, the dirt-caked beauty of Ian William Craig’s most recent music is what makes it both compelling and instantly recognizable. But it becomes clear during our conversation that Craig’s healthy restlessness will likely lead him in new directions. He is currently finishing an ambitious double album of material that spans four years, and which, he says, serves as a sort of thesis statement. He is even reworking some of his more folk-informed songs. And Matthew Sage’s Patient Sounds label is issuing a cassette release—“The most punk thing I’ve done to date,” Craig says, reflecting on its esoteric analog-only recording method. While he usually mediates his creative process with recording software, the music for this project was recorded directly to four-track cassette.

“I tend to orbit things without ever really landing,” he remarks.

Craig’s work sounds nothing short of grounded and cohesive in its current state, but it will certainly be exciting to see him fulfill the promises of this latent threat.

Top photo by Caton Diab; other photo courtesy of Ian William Craig.

Audio: "Jouska." Composed and performed by Ian William Craig. Unreleased track from Cradle for the Wanting (Recital, 2015).