“You must not carry false rumours.” These words from the Book of Exodus are the first to be heard in Dániel Péter Biró’s large-scale cycle of works, Mishpatim (Laws), composed between 2003 and 2016 and released on two CDs on the German new-music label NEOS. Of course, rumours means noise and might thereby be understood as the composer’s credo: to make true sounds—in this case, true to the Word of revelation. Biró is a U.S.-born composer of Hungarian–Jewish background, whose works often explore aspects of Jewish liturgy, scripture, and philosophy, notably circulate in the new-music networks of Europe and North America, and are frequently performed by the Montreal saxophone quartet Quasar. Currently an associate professor at the Grieg Academy in Bergen, Norway, he was a faculty member at the School of Music at the University of Victoria (where, full disclosure, we were colleagues) for fourteen years.

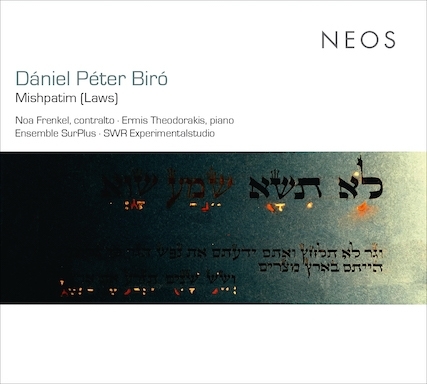

Encompassing six works and lasting nearly two and a half hours, for combinations of voices, instruments, and electronics, Mishpatim is performed here by the Freiburg-based Ensemble SurPlus with electronics by the SWR Experimentalstudio—whose collaborations with Luigi Nono struck an analogously transcendent note. Biró’s is a singular soundworld full of whispered words, piano harmonics, and “ghost instruments”—one of his signature techniques, in which acoustic instruments get “played” by electronics. The work is vocally anchored by dazzling Israeli contralto Noa Frenkel, who at times channels her inner chazanit (cantor), as in the opening of HaDavar (The Word), the first piece of Part IV. Indeed, the voice dominates throughout, which befits a work infused with chant, replete with microtonally inflected and spatially mobile chant tones. But though this music is inspired by Jewish ritual, it’s not what you expect. There are no cloying cello-sighs à la Bruch’s Kol Nidrei. And yet, affinities with Judaic liturgy permeate. The cover displays Hebrew scriptural calligraphy, with diacritical marks highlighted in colour. Biró uses this neume-like trope, the traditional notation of Torah cantillation, as a symbolic musical grammar. Moreover, the complex metrical language (those nested tuplets of New Complexity vintage) is generated via gematria, Jewish numerology that pairs words with numbers.

This is hard-edged and splendidly unfamiliar sounding yet predominately soft music: the inner fold features a typical score excerpt calling for instruments to crescendo up to a mere pianissimo. Mishpatim is inspired not only by Torah cantillation but also by various traditions of Koran recitation, and sets texts from the eponymous parsha, or section, of the Old Testament book of Exodus (and not, incidentally, from the Book of Numbers, despite the fact that counting—in four languages, Hebrew, German, English and Hungarian—is omnipresent). In addition, the fourth part, Ko amar—Thus Said, sets verses from the Book of Jeremiah (like another chant-inspired work, Stravinsky’s Threni), pairing the Pentateuch text with a passage from the Prophets, known in the Sabbath prayer service as haftorah. Certain themes emerge from the selected texts, including minority rights in Part I (“You shall not oppress a stranger”),ecological stewardship in Part II (“Six years you shall sow your land . . . but in the seventh you shall let it rest”), the legacy of a vengeful God in Part III, and the nature of sacrifice in Part V.

Don’t expect flashy electronics—the kind that sound dated in five years. In the last minutes of Part III, resonant electronic washes recall the final wistful iterations of Alvin Lucier’s I am Sitting in a Room more than they do, say, the extroverted preens of Bernard Parmegiani’s De natura sonorum. This is second-generation mixed music whose electronics never function as phantasmagoria. The CD is preferable to the streaming product (available in the Naxos Music Library), not least thanks to illuminating notes by U.S. musicologist Tamar Barzel.