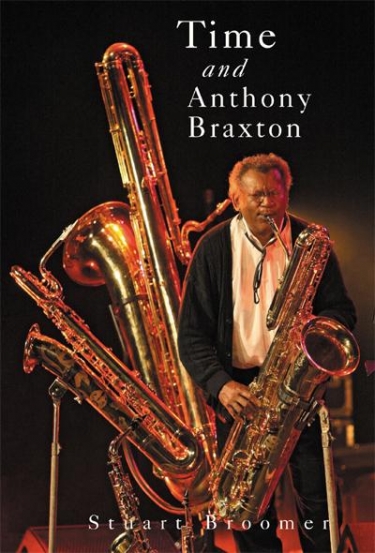

Stuart Broomer knows Anthony Braxton. He has listened to the American composer and multi-instrumentalist’s music from the beginning, attended concerts by him since the early 1970s, written about the musician many times, and over the years interviewed Braxton on many occasions.

Because of this familiarity, Broomer sets himself a more difficult-than-usual task here. Unlike historic biographies, journalistic chronicles, or transcription-heavy texts designed to demystify a musician’s style, the book focuses on how Braxton alters and dislocates time through his compositions and improvisations.

Time and Anthony Braxton offers many insights, but the sheer breadth of Braxton’s considerations and achievements may be too much even for Broomer. As he admits towards the end: “The Braxton world . . . represent[s] something akin to the solar system with planets revolving around a sun and moons revolving around planets. Hard to observe, the totality of his musical universe expands while its parts become closer together.”

Succinct and thought-provoking, Broomer’s book is studded with aphorisms like those that will no doubt enter the language of informed musical criticism. However, with Braxton able to create and record, at an astonishing pace, new variants of his music, Broomer appears to be playing catch-up. By the book’s end, some statements seem more akin to a record reviewer’s first draft of history than cerebral considerations. Itemizing Braxton’s ever-more-recent output, Broomer appears to be valiantly attempting to shoehorn everything into his thesis.

One of the most valuable parts of this volume is the author’s explanation on the origins of Braxton’s mature style. The sax player’s style derived not only from the modern-jazz tradition that extended the virtuoso speed of Hard Bop and John Coltrane’s temporal and rhythmic dislocation, but also includes the more languid influences of cool jazz, as well as the harmonic freedom of so-called serious music, from its nineteenth-century codification on to serialism and Stockhausen. “A ‘classical’ composer as well as a ‘jazz’ musician, Braxton would seek his own route,” Broomer writes, adding, “Braxton was an artist who could find new paths where others saw only dead ends.”

Additional insights include, among others, an analysis of Braxton’s compositional methodology in an orchestral work: rather than using twelve-tone rows to create equality among pitches “Braxton was concerned with the kind of porous auditory space in which musicians and listeners could move freely within a work . . . it’s a profound listening to inner and outer possibilities, so that his methodologies are dictated by the music itself.”

Time and Anthony Braxton is a necessary volume for Braxtonophiles and anyone wanting a handle on contemporary serious music. At its best, it’s a Baedeker to the frequently written-about, but rarely properly explored, sonic continent that is Braxton’s music.