The Original New Timbral Orchestra, known simply as TONTO, has been called “a synthesizer the size of Nebraska.” The appearance of this electronic monolith makes an immediate impression. Housed in a twenty-foot semicircle of six-foot-tall wooden cabinets with knobs, keyboards, blinking lights, and colourful wires sprouting from every inch of its curves, this legendary instrument could be mistaken for the deck of a space ship.

From its humble beginnings in 1968 as a Moog Series III modular synthesizer, TONTO has evolved into a musical arsenal, assembled through the addition of components from many of the world’s top electronic brands. Years be fore synth luminaries Tangerine Dream, Vangelis, and Jean-Michel Jarre found fame with their futuristic soundtracks, TONTO cocreators Malcolm Cecil and Robert Margouleff made eerily melodic sci-fi scores for the movies of their minds.

Now, after four decades in the possession of its “tone ranger” Cecil, TONTO rides on in Calgary’s Studio Bell, home of the National Music Centre’s world-class instrument and music-artifact collections and conservation and exhibition spaces. Studio Bell also features a performance hall, education centres, recording and broadcast studios, and venues.

The storied synth has now embarked on its second life, and will be available for recordings and performances created through the NMC’s artist-in-residence program. “At the NMC, TONTO will be a working exhibit instead of just [being stored in] mothballs,” says Cecil, who tells me he turned down offers from the Smithsonian, Yale, Cornell, and Bard. “I built it as an experimental instrument that would be able to do all sorts of things that people hadn’t thought of, and to create something totally new. Not just new sounds or new rhythms, but entirely original music. I think it’s a very important artifact, but it hasn’t even started to show what it can do.”

The National Music Centre is also beginning a new chapter of its story, and aims to become a hub for innovation in Calgary’s ever-evolving artistic community.

Open to the public since July 1, 2016, the $191-million Studio Bell stands in stark contrast to the history of its surroundings. In Calgary’s Avenue Magazine, writer Todd Andre described the neighbourhood prior to its gentrification: “Long stigmatized by Calgarians as declining and dangerous, the East Village was abandoned to the care of patrons in local run-down bars. Left to die by the city, the village was embraced by the down and out.” Set to a backdrop of live blues music, the King Edward Hotel was the most infamous of these run-down bars on the East Village’s Ninth Avenue, known as Whisky Row. It was also one of the first establishments in town to serve alcohol to both black and white patrons, and was busted several times by local law authorities during Calgary’s brief prohibition in the 1920s. The King Eddy has been painstakingly rebuilt as a music venue inside the Studio Bell facility, with the Rolling Stones’ Mobile Studio truck parked alongside, allowing for Eddy performances to be recorded live off the floor. It’s one of several consoles elaborately wired together with two-way Skype-style video monitors replacing the control-room glass. Within the spiralling contours of Studio Bell, any studio board can record any instrument.

Despite the dazzling modern architecture of the building, its exhibition-displays lean heavily on CanCon nostalgia. One of the first pieces a visitor sees is a hilariously hyperbolic handwritten note by Tom Cochrane on the writing of his hit song “Life Is A Highway”: “I woke up crazy early around 4:30 a.m. as I always did when life and the muse were playing chaos with my soul. ” Visitors move past smiling photos of Canadian celebrities, such as Drake and k.d. lang, and can enter an entire room dedicated to Sarah McLachlan’s Canadian Music Hall of Fame induction. Big-ticket items in the rotating collection include Neil Peart’s Hockey Night In Canada drum kit, Avril Lavigne’s “Sk8er Boi” sneakers, and Corey Hart’s sunglasses (presumably worn at night).

The true treasures, however, can be glimpsed through the glass of Studio Bell’s repair room, where electronics technician John Leimseider—a former keyboard player for Iron Butterfly—has been tooling away on TONTO since it arrived at the NMC in 2013. Just a few feet away from TONTO sits the Electronic Sackbut, the world’s first voltage-controlled synthesizer, which was built by Canadian scientist and composer Hugh Le Caine between 1945 and 1948. To the unknowing eye, this ramshackle contraption made from orange crates and two-by-fours—with a hand-scribbled note to leave a screwdriver for repairs—could be easily mistaken for a pile of garbage. This priceless artifact is on loan from Ottawa’s Science and Technology Museum, so the NMC can create a functional clone.

“Hugh Le Caine felt that putting any effort into the cosmetic appearance of his instruments was a waste of time because it wouldn’t change how they played or sounded,” says Jason Tawkin, the NMC’s manager of collections access. “When he demonstrated the Sackbut he often covered it with a sheet. People would say ‘Wow, that’s amazing’ and when he unveiled it they’d be so disappointed. It’s one of those things we never thought we would see—let alone have it here.”

Tawkin is an obsessively dedicated gearhead. After working at campus radio station CJSW, he found his dream job as the technical liaison of Studio Bell’s West Block. This wing of recording studios and instrument rooms is only made available to artists in residence. From sixteenth-century harpsichords to a synth collection that would make Giorgio Moroder’s jaw drop, it is overwhelming to say the least. Tawkin’s raison d'être is to make musicians’ ten-day stays at the NMC as productive as humanly possible. “One of the things I hate about the world we live in is that all of these high-end guitars or vintage synthesizers end up in the hands of doctors and lawyers,” he says. “Those guys put them in their house as showpieces and turn them on twice a year. They rarely make any music with them, which is really depressing. Emerging artists and other people without that kind of cash flow have far more interesting ideas. With access to new equipment and rare objects, they can do amazing things that broaden the musical landscape.

“Every residency is way too short. Ten days is nothing. But three out of the four [artists I’ve worked with] so far, made a record [here]. If you’re organized and you know what you want to accomplish, you can do a lot. The flipside of that coin is you can literally spend ten days auditioning sounds. You’ll have a great time, but you’ll walk away with zero things on your hard drive. That’s not what this is about. It’s about capturing ideas as they happen.”

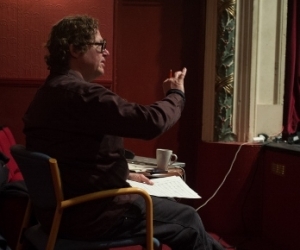

The roster to date of NMC artists in residence includes some recognizable names: Luke Doucet, Great Big Sea’s Sean McCann, and The New Pornographers’ Kathryn Calder, who teamed with Mark Hamilton of Calgary’s Woodpigeon. In addition to a “master in residence” visit from techno pioneer Richie Hawtin, the NMC recently invited experimental electronic artist Evangelos Lambrinoudis II [see photo below], who produces pummelling techno as Corinthian, hosts Natural Selection (Calgary’s longest-running hip-hop DJ night), and surveys underground sounds with his label Deep Sea Mining Syndicate. For his April 2017 residency, Lambrinoudis assembled techno producers Eric Fraser and Wax Romeo with avant-garde pianist Mark Limacher. In this genre-bending collaboration, pulsating beats ramp up the tension as fractured melodies filter out like a rave in a haunted ballroom.

“The album we recorded explores themes of disappearance,” says Lambrinoudis. “It depicts people who go missing and those who are intentionally gone. That includes my own desire to disappear from the zeitgeist of social media where we’re being surveyed. What you’ll notice compared to my previous releases is that even though it’s hard techno, it releases into tender and vulnerable moments of insecurity.”

Since Studio Bell opened to the public in 2016, access to the collection and its accompanying resources has been extremely limited. Tawkin says innovative ideas benefitting both the artist and the residency program’s reputation are the most important criteria for applications. Inviting to the program an active figure in Calgary’s forward-thinking music communities, such as Lambrinoudis, is a step in the right direction.

“Who you are helps a little bit,” Tawkin says, “but that’s not as important as applications [that say] ‘I need an EMS Synthi 100 for this project.’ You’re not going to be able to [find] that anywhere else, so it moves you up in the ranks. We want a symbiotic relationship, in which the residency is just as good for [the artist’s] career as it is for our organization.

“By increasing our music scene’s profile, [we’ll motivate] artists from all over the world [to] visit. People are also scouting local talent for their residencies. If they need a cello player or horn player, we’re getting session work for Calgary musicians. New connections are being made.”

“The NMC is building slowly and I understand why they’re taking that approach,” Lambrinoudis says. “I think the purpose for their gatekeeping at this point is to make sure the program is fully realized. When they allow people into the studios there’s a tax on the collection. They don’t want to create a huge buzz, open the floodgates, and then have it blow out. Whether or not they allow more local musicians in remains to be seen.”

Sarah Davachi has worked in various roles at the NMC since 2007. While employed as developer of collections content, she became a celebrated electroacoustic composer and performer. Many of Davachi’s drone-based works combine vintage synthesizers with acoustic instruments and manipulated sounds. While working as a tour guide at the museum’s former location, the Customs House building, her down time became a creative springboard. “When nobody came on tours, I would sit around practising and trying out new instruments,” says Davachi. “That definitely had a big influence on how I made music. Not the will to do it, necessarily, but the ability to take the next step. I had to be there for four or five hours anyway, and the instruments were all laid out in one big space. You could walk across the room and play something totally different. I was overwhelmed by the possibilities.”

Davachi also notes that Studio Bell is taking a cautious approach to building its profile, as it works out the kinks in its residency programs. She remains optimistic about the future of the facility and hopes that its instrument collection can become more widely accessible. “The mandate for the residencies is to represent as many different things happening in music from across the country,” says Davachi. “That’s not necessarily in line with who could be using it effectively. Right now they’re trying to gage how different types of musicians interact with it all. It’s almost like a guinea-pig program to see what works well and what they can tweak. There’s a lot of potential.

“One way [Studio Bell] can fill a void in Calgary’s music scene is by hosting more special events. There aren’t many places where early music, electronic music, and improvised music can be performed in the same location. It’s not just offering a space for those kinds of events, but also connecting them to the collection. There are so many fascinating instruments that could be pulled out of studio spaces where people normally don’t have access [to them], allowing them to be played and heard.”

Malcolm Cecil would agree with that sentiment. After seven years of searching for TONTO’s final resting place, he settled on the NMC, where, he believes, it will captivate both visiting artists and the general public. “Of course, when it goes on display, somebody has to be watching,” he says, with a wink. “You don’t want kids sticking chewing gum on it.” If and when the historic instrument is returned to working condition, Cecil hopes TONTO will be used for recordings and in live performances. He looks forward to visiting it, and is proud to have it live in Canada, a country “like other areas of the Commonwealth, where art and preservation of the past are important.”

Cecil firmly believes that the object of his musical legacy has yet to reveal its full capabilities. “I would have liked to see another zero on the end of what I [sold] it for, but I haven’t had one sleepless night,” he says. “I’m eighty, so I couldn’t keep it up. I wasn’t earning enough money to continue the development. What would have happened if I passed away and TONTO was still here in my house?

“[After] Adolphe Sax invented the saxophone, it took Charlie Parker over 100 years to show people how to play it,” Cecil finishes with a laugh. “I’ll be pushing up daisies for decades before someone figures out how to really use TONTO.

Top photo by: Don Kennedy, courtesy of Studio Bell. Photo of Corinthian during his residency at the National Music Centre by: Baden Roth.