CERTAIN LABELS are very much the product of a particular vision and exude cohesion of an almost iconic order—one that even seems to magically weather shifts in taste and approach. ECM’s elegant black and white photography, sans serif typeset, and crisp, reverberant sonic profile is a universe unto itself, carefully sculpted by its founder Manfred Eicher, who produces most of the label’s output. Daniel Kernohan and Vern Weber’s label Spool, after emerging in the late 1990s, certainly carved out its own place. Though neither party could be framed as the label’s curatorial protagonist, there’s no questioning its catalogue’s clear visual sensibility, or the pair’s acuity, but at its core Spool was and is, above all else, an organic expression of several intersecting communities.

In 1985 Kernohan established Marginal Distribution. Having worked as a buyer for radical Toronto bookstore SCM Book Room, on the ground floor of what was once Rochdale College, he had acquired a firm grounding in North America’s vital DIY publishing industry. At the same time, he was an active member of the tape-trading community, where weird homespun recordings would brush up against the likes of Al Margolis’ cassette label Sound of Pig and Harvestworks’ Tellus series. His literary and musical worlds converged in Marginal Distribution’s wondrous catalogue of books and records.

At some point Kernohan ran the operation out of a humble lower-level, low-traffic storefront in Peterborough, Ontario. Weber was at that time acquainting himself with the town, having recently moved from Victoria to pursue graduate work at Trent University, and he saw some of his favourite recordings in an inconspicuous window display. It was, he says, “a one-stop shopping mecca for all your small-press, small-label print and music artifacts of various radical orientations.” He and Kernohan struck up a friendship. Weber began working in the store on Saturdays, and the two started a radio show, Broken Radio, on the university station.

The early ’90s recession hit Marginal Distribution hard and Kernohan eventually sold its literary branch. The musical side of things was another story. After a short break, it was rechristened Verge Music Distribution and again began offering up left-field material. Weber had moved back out West but was invited aboard Verge as a sales representative, and the two men would meet up in Ontario for an annual road trip out to the Festival international de musique actuelle de Victoriaville. It was during one of these car rides, in 1996, that Spool really started to hatch. Their first demo tape arrived before they even had a label on which to issue it. Percussionist and educator Dylan van der Schyff, a staple of Vancouver’s creative music community, being aware of Verge’s formidable network of labels, was eager to probe Kernohan for advice about where to submit two prospective releases. The material van der Schyff sent wound up providing Spool with its first two releases: van der Schyff and Chris Tarry’s Sponge, a transmission “from a nether corner of the ambient world” according to Spool’s Web site, and These Are Our Shoes, a series of eighteen duets from van der Schyff and cellist Peggy Lee.

Spool’s first ten years yielded some forty-odd sprawlingly diverse releases tucked into a handful of geometrically themed subseries. The improv series Line is the largest, containing thirty discs. The five releases in the Field series document different sound-art practices, whereas Point (its composition series) and Arc (its “rock art” series) contain three releases apiece. In spite of this orderly outward appearance, which definitely enhances the label’s air of aloof mystique, each of these categories is delightfully chaotic, their wildly varied contents freely spilling over into one another.

There’s a strong emphasis on Canadian artists, but many releases feature well-known international players, often performing within unique combinations. Port Huron Picnic is an agitated and angular trio consisting of Torontonians Kurt Newman and Mike Gennaro with Swedish saxophonist Mats Gustafsson. Fred Frith, John Butcher, Gino Robair, and Joëlle Léandre all appear in different and equally inspired combinations throughout Spool’s discography, while other releases include Wilbert de Joode, Michael Moore, Dewey Redman, and Ken Vandermark. On the label’s final release before a seven-year hiatus, Anthony Braxton leads the hulking AIMToronto Orchestra through his preposterous and beautiful compositions.

“It happened,” says Kernohan of their A&R strategy (or rather, lack thereof), “not with a kind of deliberate production ideal or aesthetic, per se. It was more to do with connections and things that are offered. Sometimes it was something that we knew and sometimes it wasn’t.” Weber recalls one of the few exchanges around the reigning aesthetics: “Dan and I had to have a discussion about whether the first Peggy Lee Band recording fit the label’s profile. We didn’t know what that profile was, really, and had not been trying to cultivate a profile, but Peggy’s CD was so beautiful in ways that nothing we had previously released had been. We were wondering if it was too beautiful for us. Hilarious!”

In 2009, with physical music becoming an increasingly awkward proposition, Verge closed its doors. Although Spool stopped releasing new recordings in 2008, it never officially ceased—in fact, its entire back catalogue remains widely available through all of the major online outlets. Then, earlier this year, Kernohan, who some years ago had moved to Uxbridge, resurfaced with Spool’s newly minted Spurn series. Congruent with Spurn’s designated bailiwick of “Irreverence,” it features some of the label’s most personal and least-classifiable output thus far. In one way, it marks a return to his roots in the nascent cassette scene—each release thus far is very limited, carrying the spirit of private-press experimentalism.

Car Dew Treat Us (Spurn 2), as one might anticipate, draws directly from Cornelius Cardew’s

Treatise, with performers selecting pages from the work at random

. Kernohan (billed cryptically as DK) leads a group named The Perfectly Ordinary (Allison Cameron, Rod Dubey, and Lawrence Joseph). There’s a different guest artist for each of the ten tracks (all of which clock in at a cheeky four minutes and thirty-three seconds). The all-star cast includes Al Margolis, Paul Dutton, Caroline Künzle, and Gino Robair. Text fragments—drawn from Beckett, Confucius, and Cardew—appear intermittently. One might expect these to provide something more tangible for listeners, but instead they serve to enhance the CD’s disorienting quality.

Shed Metal (Spurn 1) by Equivalent Insecurity, another Spurn offering, also features Kernohan, this time alongside longtime associate Dan Lander (Marginal helped distribute an early Lander cassette). With its viscous electronics, cryptic pulsations, and grey, lo-fi varnish, it comes off like some distant and feral cousin to Brian Eno’s more fragmentary efforts, albeit laced with a strange sort of muted anxiety. It’s got all the psychedelic makings of some long-lost obscure gem, begging to be reissued—which is exactly what it is: these vignettes hearken back to 1987–89, when Kernohan still lived in Toronto, which accounts for their eccentric, hermetic demeanour, at once unbridled and tentative, unkempt and neat.

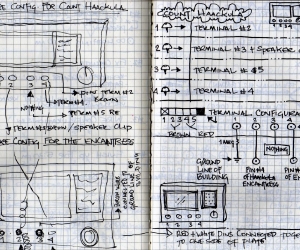

The third Spurn title, not released at press time, is even more archival in nature. Electronic-music composer Terry Rusling (1931–74) was the uncle of a close high-school friend of Kernohan’s, and upon learning of Daniel and his friends’ burgeoning interest in visual art, gave Daniel multiple avant-garde LP sets, one of which included Cardew’s Great Learning. “I see that as a turning point,” states Kernohan. “[Rusling] is probably one of the key people who made me who I am.”

Unbeknownst to the teenaged Kernohan, Rusling had worked on staff as an engineer at the CBC and subsequently joined the graduate seminar of Dr. Myron Schaeffer at the University of Toronto, thus being able to use their electronic-music facilities during their heyday—when Hugh Le Caine’s inventions were on site and the likes of Pauline Oliveros and John Mills-Cockell were beavering away behind the knobs and reels of tape. Further, Rusling had been mentored abroad by Stockhausen. According to Kernohan, the forthcoming career-spanning disc will constitute Rusling’s only formal release thus far. Material for this homage to the little-known composer is still being selected.

Beyond that, the future of Spool remains as uncertain as ever, but given Kernohan’s ongoing investment in and curiosity about creative music of all stripes, going back several decades, one can rest assured that there’s something else on the horizon. In an age where small labels rapidly come and go, Spool’s uncharacteristic endurance and adaptability is cause for celebration. There’s no clear “Spool sound” or set M.O., but perhaps this enigmatic surface is the key to their longevity.