On Xuan Ye’s website, layers of text, symbols, and images float across the home page like something halfway between poetry and code. The site is an ever-changing digital archeology of her artistic works across a wide range of sonic and visual media. All of it defies categorization. In concert programs, the first sentence of her bio has often read: “Xuan Ye is the prototype of many objects.”

A Web developer, an installation artist, a multi-instrumentalist, and an improviser, Ye is an artist whose practice is plural in scope. At its most characteristic, her work is a synthesis of forms, incorporating language, the body, sound, and code. And though it often pulls apart at the sinews of new technologies, it isn’t so much a critique of digital culture as it is a disruption of it: artworks that seem to give to computational structures physical, malleable forms, and an improvising practice in which acoustic and electronic sounds overlap to generate textures that feel visceral and real.

She has performed her music in China, where she was born, in Canada, where she is now based, and elsewhere, employing varying combinations of voice, keyboards, guitar, objects, and electronics. “You know, now, looking back,” she says during an Internet call in January 2020, her voice grainy and flattened in the computer speakers, “it’s almost as if music changed my life.”

Xuan Ye was born in a small town in the Chinese province of Hunan and grew up in Xiaocuo (Fujian province), where she started studying the piano at age five. At eleven, she left home to attend a boarding school for music in Gulangyu—a Chinese island with a colonial history that gave it a strong classical-music presence, earning it the moniker Piano Island. Leaving her hometown to study music was a liberation that became an oppression; soon after arriving at music school, she started to hate it. “I was so young and far from my parents, and the training was very intense,” Ye says. “By the time I graduated, my parents and I felt exhausted just by going in this direction. So, after middle school I completely stopped playing the piano.” Her musical interest persisted, though, and when she moved to Shanghai to study e-commerce and financial engineering at university, Ye absorbed everything. She joined bands, and developed a following as a pop singer-songwriter on the social network Douban. After graduating, she worked as a bar singer at night while working nine-to-five as a data analyst. She later quit the day job and worked full-time at a bar in the Yunnan-province city of Lijiang, singing standards for up to eight hours a day.

“I tried so many different kinds of things,” Ye says. “I was doing R&B singing, I was a pop singer, I had a punk band, and I played guitar. I had access to a lot of new things, and at the time I was so into it—all of these different underground movements in the West, all of those musics.”

Much of Ye’s work is concerned with breaking codes—both digital and cultural—and with unlearning certain ways of being. At the beginning of her experimental-music practice, she was drawn to sounds like screaming, electronics, and noise, as a means of disentangling herself from the pop and classical training of her upbringing. “It took me so long to clear my body of that,” she says. In 2011, Ye moved to New York City and majored in sound studies at NYU, focusing on the philosophical dimensions of sound, sound art, and pop-music culture. She then moved to Toronto, where she works as a Web developer, and in 2018 she received her Master of Fine Arts degree in visual arts from York University.

Ye admits that it has been challenging to coalesce the various streams of her life into a unified artistic practice. “To me, there’s a fundamental difference between them, because when you perform music … your body is demanded to be present,” she says. “When you conceptualize an installation—even though it involves intuition—eventually it’s a rational process. I guess because I haven’t practised visual art that long compared to performance, I still can’t find the agency of my body in the making process.”

Because she holds space within herself for so many disparate practices simultaneously, Ye feels as though life requires her to be organized. Performance, with its fluidity and ephemerality, provided a space where she could be freer, and less database-like in her thinking. “People whose medium is painting, they probably find that same kind of feeling in painting,” she adds. “But music is that medium for me.”

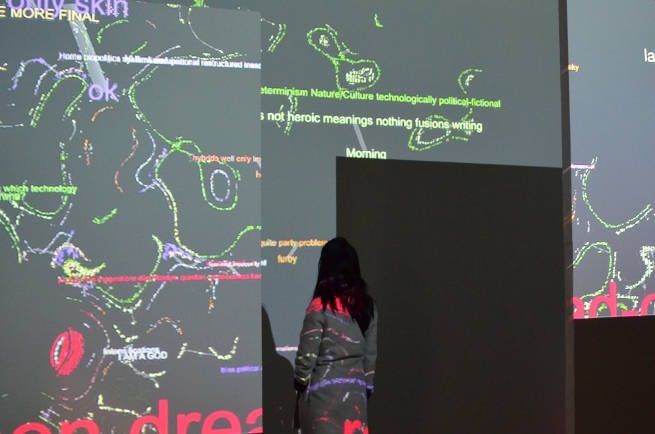

I first encountered Ye’s work in 2018. Her thesis solo exhibition for her master’s studies, entitled Et Cetera, was presented at Toronto’s Trinity Square Video, Canada’s oldest media-arts centre. Using a range of physical and digital media, the exhibition depicted forms of human–machine coupling to confront issues of language, subjectivity, and code. One of the works, EveryLetterCyborg (above photo), is what Ye calls “computer-generated uncreative writing”—an artwork that accepts input text and algorithmically translates it, using language from Donna Haraway's 1984 essay Cyborg Manifesto. The algorithm translates every letter of the inputted text into words from the essay, while simultaneously jumbling and fragmenting the syntax. Version 1.1 of the project was an interactive Web installation that invited the audience to input text into a Web interface, which in turn output speech-to-voice sounds. The version of EveryLetterCyborg that I saw—Version 1.2—was presented as a physical representation of a TwitterBot that tweeted randomized phrases twice per day, printing those tweets onto a gradually unravelling roll of receipt paper. That same year, during a residency at the Toronto artist-run centre InterAccess, Ye developed EveryLetterCyborg Version 1.3, an interactive installation using crowd-input texts that Ye mapped as projections, in WebVR, and as generated sounds. It’s one example of how Ye’s work in the digital realm reaches towards something both physical and musical—an idea that lately has been at the crux of her practice.

“I spend most of my life in [sic] a computer,” she says. “And inevitably, that process absorbs my body. So that’s why now I want to have more tangible things: I want to play with making objects sound.”

The first time I saw Ye perform was in December 2018 in Toronto, at a concert in the Emergents series, which I curate for the Music Gallery. Earlier that year, she’d told me about her interest in creating sonic ecosystems of objects and feedback. At the Music Gallery, she performed Feng Shan, a minimalist, long-form solo improvisation using piano, electronics, and three amplified electric fans, which generated shifting feedback tones as their heads rotated from left to right and back again.

In November 2019 the Beijing-based label Zoomin’ Night 燥眠夜 released a recorded version of the project (feng shan 2.0) on cassette—the second of three releases for Ye in 2019. The first was Breath Fractals, a duo cassette with Nova Scotia-based jaw harpist chik white that juxtaposes vocals and field recordings from Ye against white’s vocal–jaw harp ostinati. The third was the solo LP xi xi 息息 (Toronto’s Halocline Trance), a compilation of live and studio improvisations recorded between 2016 and 2019. Although the online description refers to it as Ye’s debut LP, the recording nonetheless marks the end of her current approach to music; she’ll be taking a break from the kind of improvising that has formed the foundation of her current practice, and xi xi 息息 is her sonic summary of that work.

The B side of the album is one live set from 2016 that is cut into five different pieces. The A side features four discrete tracks, each using a different setup. Electronic sounds figure heavily on both sides, either as haunting backdrops or built into blooming transitions that force the music forwards or sideways. But while many of the techniques on the album could plausibly fall in the electroacoustic music genre, electronic effects aren’t something Ye is concerned with. On the first track, “below beyond green 绿,” she sampled three octaves of her vocal range and fed them into a Max patch on her computer. Rather than trying to change the sounding qualities of her voice, though, Ye simply used the patch to randomize the note sequences; in the final track, the samples themselves remain totally unprocessed.

Ye was determined to include her own voice—with or without electronics—on the A side of xi xi 息息. It’s present in some way on nearly every track. “Voice is something I've always been interested in, and it’s always felt natural to me—ever since I had a sweet voice, playing bossa nova songs [in Shanghai],” she says.

“I know I have been experimenting and radiating this territory of my identity,” she adds. “But I also want to find who I am—and what really comes naturally to me—through this process.”

In 2020 and beyond, Ye intends to return to the idea of the voice in a more formalized way, by making songs, writing lyrics, and singing them. After moving to New York and shedding her singer-songwriter activities, Ye periodically returned to working with song-like forms. In 2014, she collaborated on an album of sound poetry; in 2019 she incorporated lyrics into some of her live performances. Her work in the near future will simultaneously return to and depart from those past practices.

The ideas of connections between history and future, of paradoxical circumstances, and of music as a space for emotional embodiment and reflection are at the core of how Ye thinks about her work as a musician. “I never talk about personal narratives or use them as the basis for creating art,” she explains. “But we have talked about the idea of the paradox—and that is very present in how I view the world. For me, keeping a music and art practice is a way to deal with that.”

On the first three tracks of xi xi 息息, Ye uses an electronic module for real-time biofeedback called MIDI Sprout, which, when touched, translates electrolytes present in the body into MIDI. Others have used the module primarily as a way of sonifying plants. “Plants never say that they want to be heard,” Ye says—and, after a pause., “but I use my own body.”

Listening to those tracks, you can sense the audible connections between the voice, instruments, and electronics. I don’t know if it’s possible to hear with exactitude the ideas beneath it all—to identify certain sounds as the automatic sonic byproducts of someone’s body wanting to be heard—but there is an intent there that is palpable to the listener’s imagination. A truer understanding of how all of the details in this music inform each other seems just out of grasp—though maybe that’s the point.

I keep thinking about Ye’s notion of a person as a prototype, that all of the complicated parts of an artwork’s ecology—hybridity, chaos, noise—can be traced back to a personal origin. In Ye’s music, the connections between the self, the body, and the sounds it produces feel fibrous and tangible. You can hear them. Ye says a common connotation of her album title xi xi 息息 is “intrinsically connected.”

“My intention is to create not just this world, but very literally me—connecting with digital machines that connect to all the other non-human agents, to objects,” she says. It’s the last thing she speaks about before we hang up and I close my computer: “Everything at the same time, in that process; it all kind of feeds back to you.”