I. White Fang, Chapter I[1]

A vast silence reigned over the land

on every side was the silence, pressing upon them with a tangible presence

a faint far cry arose on the still air. It soared upward with a swift rush, till it reached its

topmost note, where it persisted, palpitant and tense, and then slowly died away

a second cry arose, piercing the silence with needle-like shrillness. It was to the rear, somewhere in the snow.

a third and answering cry arose, also to the rear and to the left of the second cry.

hunting-cries that continued to rise behind them

a long wailing cry, fiercely sad, from somewhere in the darkness

cry after cry, and answering cries, were turning the silence into a bedlam. From every side the cries arose

the dogs became quiet.

now and again snarling menacingly

II. Surfacing, Chapter II[2]

gravel pinging off the underside of the car

rapids topple over the rocks, the sound rushes

it was dead silent, they could hear what they thought was the howling of wolves, muffled by forest and mist

Then there was the pouring noise of the rapids

the howling was the village dogs

the hush of moving water

(leaders roaring at the crowds)

III. Roughing it in the Bush, Chapter III[3]

the bugle-call wafted over the waters sounded so cheery and inspiring

A loud cry from one of the crew

Cries of "Shame!" from the crowd collected upon the bank of the river

splash! a sailor plunged into the water

an exclamation of unqualified delight

the close, dusty streets were silent

The sullen toll of the death-bell

thunder and lightning, accompanied with torrents of rain

noise and confusion prevailed all night

Reflection: Sometimes the sound that doesn’t sound makes the loudest sound—even if it’s all in our own heads. Even when conducting a silent activity such as reading a book, our ears—or perhaps our mind’s ear—can be abuzz with a cacophony of word-sound relations. Canadian literature has always seemed to me inextricably linked to the country’s vast landscape. Concurrently, Canadian sound artists have long been preoccupied with field-recording these same landscapes. In this work I make a small conceptual leap, binding together these two fields and textually “field-recording” the landscapes of some of Canada’s finest literature. The spaces may be imagined, but the sounds are real.

[1] London, Jack. White Fang, 1997. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/910.

2 Atwood, Margaret. Surfacing. New Ed edition. London: Virago, 1997.

3 Moodie, Susanna. Roughing It in the Bush, 2003. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/4389.

FYI: For “Three Literary Field Recordings,” Luke Nickel retyped all the text; I and III were taken from public domain online sources (Project Gutenberg), and II from a physical book. The piece became the basis of a performance piece—“White Fang Field Recording” by Luke Nickel—involving multiple readers silently reading books and reading aloud the sonic text: it was presented in June 2015 by the artist collective Bang the Bore at Cafe Kino in Bristol, U.K.

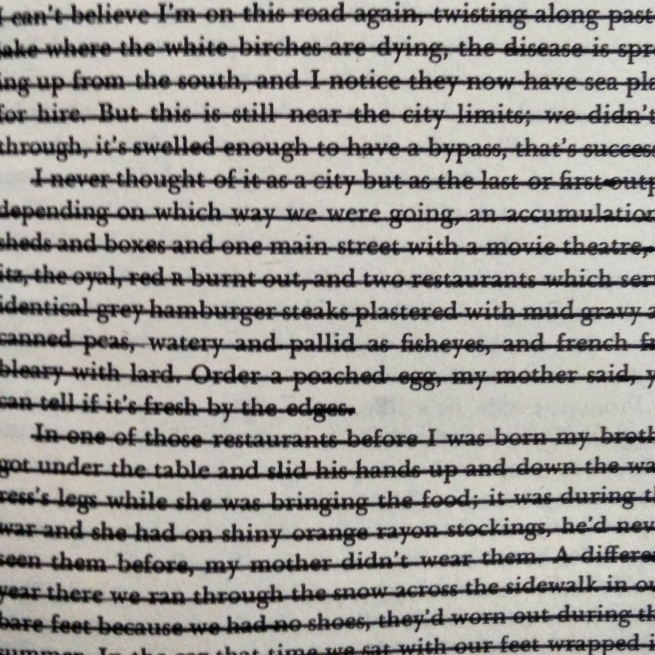

Image: Redacted text from Margaret Atwood's novel Surfacing, prepared for a performance piece by Luke Nickel, who explains: “No sound words in that section, so no text is left without a strike through it!”