There’s a strange duality about the music of Strasbourg-based Canadian composer Samuel Andreyev.

His official bio states that his compositional process is “marked by a rigorous perfectionism,” which might immediately provoke the lazy cynic to slap it with the ultimate new-music pejorative: academic. His nimble ideas are, without fail, framed in tight, tidy structures and tasteful, almost covert, virtuosity. Yet this exacting precision is motivated only by a staunch fidelity to his own instincts—he’s the furthest thing from academic. “Intuition has been my main guide throughout my entire career so far, for better or for worse,” he says.

The music’s tautness conceals profound eccentricity: wild colouristic imagination and quick, perverse wit come together in dramatic shifts of hue. It often seems to turn inside out at a moment’s notice, yet uncannily maintains its cohesion. Firmly grounded in the phenomenology of sound, his music thwarts overwrought conceptual speculation.

A conversation with Andreyev reveals similar dualities. Arriving on our Skype call, he’s seated before his stocked bookshelf in a crisp shirt and tie. He exudes a studious, serious quality. For anyone who’s watched the incisive analyses on his widely followed YouTube channel, this scene would be as familiar as the effortless eloquence with which he speaks. Despite this formality, he’s utterly candid and eager to furnish any detail of his unusual artistic journey.

Andreyev was born in 1981 in Kincardine, Ontario, and moved to Toronto in 1988. Nurtured by inquisitive and creative parents, his aptitudes and aspirations in multiple creative realms crystallized rapidly. Trips to visit his uncle Greg Curnoe, a renowned visual artist and cofounder of the Nihilist Spasm Band, were also formative. “I was struck by the fact that he had created an entire world for himself,” recalls Andreyev of Curnoe’s studio, a repurposed lithography plant in London, Ontario, that was brimming with curios, from vintage experimental music LPs to an extensive collection of bottled Canadian soft drinks. Curnoe always provided insightful, stimulating feedback about the comics his nephew drew—a childhood passion that has a palpable, important connection to Andreyev’s current work. “Despite the incredible limitations of the medium, there are so many artists that manage to invent these unbelievably rich worlds,” enthuses Andreyev. “These worlds encapsulate an aesthetic, world view, value system, sense of narrative, and sense of humour. I love the idea of condensing all of that into a very small space and into something that anyone can understand.”

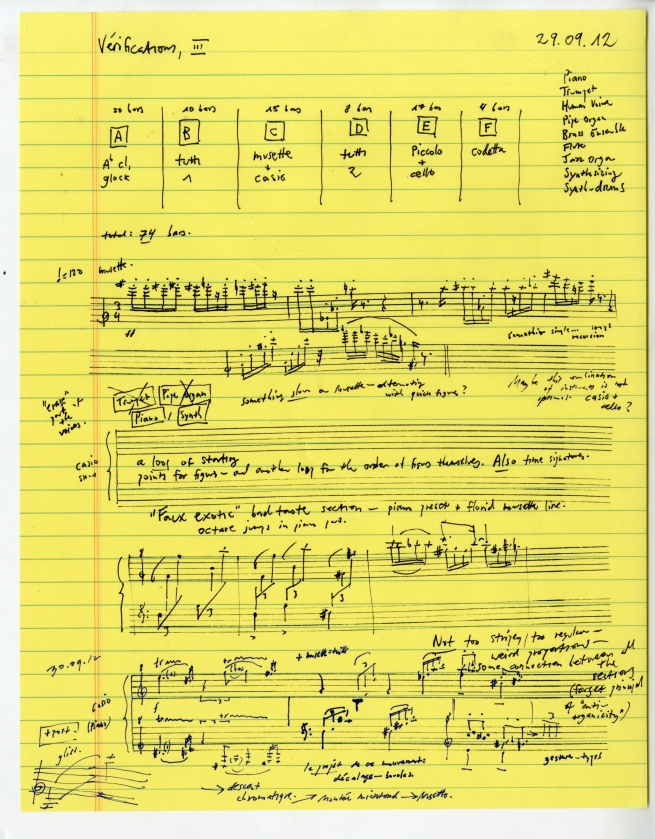

Vérifications (2012) [see composer's sketch above], the chamber work that opens Andreyev’s 2018 portrait disc, Music with no Edges, is one of his more explicitly comics-derived pieces—with what he terms its “Tom-and-Jerry maniacal strangeness” and “weird primary colours.” His affinity for episodic form, heard there and elsewhere, also reflects the panelled dispersion of the story line in comics: “You don’t have spatial depth, you don’t have narrative depth; so, what do you have left, and how do you play with those remaining parameters?”

Andreyev’s youthful creative pursuits grew increasingly eclectic, his commitment to them more steadfast. Summoning the energy for curricular work was at times, he says, “a Sisyphean struggle.” At age thirteen, alongside training on violin, cello, and oboe (which remains his primary instrument), he began notating his own melodies on scraps of manuscript paper. He also penned marble-mouthed verse, and in 1998 founded his own publishing house, Expert Press. His uncle, who died when Andreyev was eleven, had stirred in him an appetite for intensive discussion and debate, a hunger that was sated by a headlong plunge into Toronto’s zine and chapbook underground of poets and artists. Artist, writer, and owner of the Torpor Vigil label, Steve Venright knew the sixteen-year-old through these literary circles and through his stepson, a classmate of Andreyev at an alternative school. “Sam made a vivid impression: very formal in attire, right down to the immaculate spats,” Venright drily recalls in an email, “but somehow without pretension. One day he came over with the tape of a new album he’d put together . . . Turns out it was the seventh one he’d written, recorded, and released on his own.”

Informed by the likes of the Velvet Underground, Robert Wyatt, Van Dyke Parks, and Syd Barrett, Andreyev’s early songs teemed with personality. Venright assumed an active role in stoking Andreyev’s increasingly ambitious vision. He assisted him in manoeuvring out of his parents’ garage and into a proper studio. He also issued his albums alongside the suitably odd roster of sleep talker Dion McGregor and poet Christopher Dewdney.

An LP of quartets by the Second Viennese School was a shock akin to “discovering an entire planet of meaning” and sent seventeen-year-old Andreyev reeling down the rabbit hole of composerdom. He found Paul Griffiths’ book Modern Music at Toronto’s Seekers books, and later saved up for the $178 score to Stockhausen’s Gruppen.

Andreyev moved to Paris in 2003, the culmination of a longstanding dream. The transition was humbling. Andreyev’s defiantly independent streak had always been bolstered by community in Toronto. The absence of these peers left him feeling isolated. Between studies and working as an oboist and music copyist, the labour of composition started to exert itself more acutely. Most of his compositions of that time garnered little recognition or financial reward and were only performed for the first time ten years later. At age twenty-five he enrolled in the Paris Conservatory. His teacher Frédéric Durieux offered practical wisdom, helped refine his sense of harmony, and dislodged some of the extraneous detritus in his work—ideas that hadn’t been fully digested, what Andreyev calls “new-music tics.” He acquired bachelor’s and master’s degrees there.

In 2012 he felt that his patience and diligence were starting to pay off. He won the Henri Dutilleux competition for his septet Night Division (2008–10) and secured a year-long residency at Casa de Velázquez in Spain. The unmitigated space to compose and the stimulating community engendered in him a more relaxed, playful approach to writing music. Significant opportunities opened, including regular performances of his works and a recording by Ensemble Proton Bern entitled Moving.

Andreyev likens the beginning of his process to fishing in the very depths of the ocean. “You can’t see anything: it’s pitch black but you can sort of grope around and sense that there are these forms there,” he says. “Eventually, you can sort of start to understand their material qualities: is it spongy? is it hard? is it perforated? is it a resistant object?”

Any given piece goes through two full drafts. The first explores these elusive possibilities; the second is an assured and conscientious statement of vision. His rigorous scrutiny is especially audible in exceptional sensitivity to each instrument’s individual voice. Andreyev is judicious about using so-called extended techniques and just as often honours instrumental identity—embracing their distinct limitations and combining them into unusual sonic bouquets. He conjures strange perceptual magic using only everyday techniques: the phantom vibraphone resonances that haunt the pauses of À propos du concert de la semaine dernière (2013–5), or the sudden introduction of vibrato partway through the vibraphone duet Stopping (2006).

The wide-eyed fascination with instrumental colour often leads him toward peculiar choices. Vérifications and his cantata Iridescent Notation (2012–17), which had its world premiere in September 2018, both employ the classic Casio SK-1 toy keyboard, and its crude approximations of piano offers surreal commentary. These peculiar choices have also created obstacles. “I wrote a long string of pieces that were completely utopian. Zero performance prospects. Really difficult pieces requiring exotic, difficult-to-find instruments.” His works for heckelphone and lupophone, two lower-register relatives of the oboe, were among those that took several years to complete.

To Andreyev, Iridescent Notation represents a continuation of his singer-songwriter thread, last heard on his song album The Tubular West (2013, Torpor Vigil). Certainly, the text for Iridescent Notation—Tom Raworth’s poetry—shares the restless quality of Andreyev’s own feverish phonetics. It also begins with bold and raunchy wind timbres that shimmy through a maze of assertive—and even driving—percussive interjections. It’s as slapstick as it is rock ’n’ roll. The way his instrumental sensibility translates to the voice is equally striking. The soprano soloist’s part is taxing and unconventional: she busily hurls her voice across its full range—pitch, dynamic and otherwise. Yet the writing always inhabits the body naturally, and Iridescent Notation’s more melodic orientation flatters this idiomatic element.

“I’ve done a lot of thinking about where twenty-first-century music is,” notes Andreyev with his quintessential astuteness. “There’s one important distinction, and it’s something that’s pretty central to a lot of my work. It’s the idea that, fundamentally, the different parameters of composition, of sound, can no longer be in any sense abstracted out from each other and thought of separately. I can only think of it as a kind of holistic entity in which pitch, duration, intensity, and timbre are all of equal importance and they all work together as a complex, multilayered sonic organism. I think that’s something you see across the board in music, regardless of genre.”