In 2012 the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) began to tear down its Radio-Canada International towers in Sackville, New Brunswick (home to some 6,000 people and best known as the locale of the beloved SappyFest). The dismantling of the towers wasn’t just another chapter in the public broadcaster’s ongoing fight to keep its funding, but something more: a signal (no pun intended) of the end of an era.

But what struck Amanda Dawn Christie, an interarts visual and sound artist, was not just the loss of the physical towers but also of the “ghost” broadcasts that had emanated from domestic metal appliances and the like in Sackville for decades. Christie’s curiosity resulted in her documentary Spectres of Shortwave (2016), a “ghost story” about the radio signals that “haunted” the small town. It’s worth noting that she shot the movie on 35mm film, and was intentionally, as she says, “documenting a dying medium with a dying medium.” The film is marked by an intricate soundscape, which infuses the landscape photography with an uncanny feel. And the film also acts as a stand-alone radio documentary. “Every time it screens,” Christie says, “I find a shortwave radio station willing to play it in some other part of the world.” In this way, Spectres takes on the disembodied quality of its very subject matter.

While Spectres continues to make its festival rounds this year, Christie has already begun to explore similar themes of decay, absence, and invisible presence in a new project called Requiem For Radio. Consisting of five segments (Pulse Decay, New Dead Zones, Radio Cowers, Full Quiet Flutter, and Deviant Receptions), Requiem involves a complex combination of music, performance art, interactive installation, and the crafting of a new instrument. (Christie is clearly living up to her multihyphenated bio.) It’s the new instrument, perhaps, that seems the most ambitious.

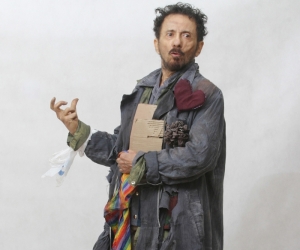

Christie describes the instrument, which is still in process of creation, as being like a cello, though the similarities end with being upright and stringed. It features a bow stick made of cow bone, with the bow attached to elbow-length leather gloves (the materials are all from cows that lived near Sackville’s radio towers). Most strikingly, the instrument’s sound is transmitted through an amplifier and a radio transmitter that are mounted to the left glove. It’s hard to describe, let alone imagine, but Christie neatly sums it up by calling it a “blend of flesh and bone and electronics.”

Fittingly, given Christie’s past work, the philosophy behind this instrument is the exploration of touch—or the lack thereof. Theremins (the 1920s electronic instrument played by manipulating sound waves) have become a large part of Christie’s work, and here again, she examines “contact through energy and not matter.” It’s a concept that, as she notes, goes far beyond music. “There are so many things we take for granted now—the Internet, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth. They’re all passing through us at the same time, but we don’t give it a second thought.” With Requiem for Radio, Christie hopes to make people pause.