Winter was ending. You could tell, because the sun had returned. Geronimo Inutiq borrowed his sister’s Ski-Doo and rode it past the Iqaluit city limit. The horizon stretched out in all directions: no trees, no buildings, just sky and ice, illuminated by light. “You feel quite small,” says Inutiq.

“It’s a humbling thing.”

Then, he listened—not with his ears, but through his boots. When the sun hits, ice starts to break. Wind blows through every crack. Growing up on Baffin Island, Inutiq loved ice jumping, the springtime game of hopping between melting ice floes without falling into the freezing water. While snow on pavement crunches underfoot, the sound of sea ice, metres deep, plays a resonant bass note. He regretted leaving his microphone behind. “But even then,” he says, “it’s quite the challenge, being able to record those sounds. You feel it somehow. It’s hard to translate that.”

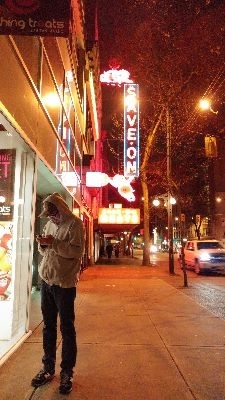

Inutiq, thirty-nine, is a musician and media artist. His eyes and ears seem constantly alert. They follow whatever catches his attention. He wears black square glasses and keeps his white-flecked dark hair and beard scraggily close-cropped. Since moving to Montreal in 1998, Inutiq has worked in a variety of genres. His work spans sound and image, tradition and technology, and is equally at home at the National Arts Centre, the Vancouver Olympics, Berlin’s Transmediale—or in an abandoned tunnel under the blinking red marquee of Montreal’s Five Roses flour mill.

For over twenty years, Inutiq performed as DJ madeskimo before retiring the controversial moniker. “It was liberating for me to give up this loaded language: mad Eskimo.” But now that he works under his birth name, Inutiq longs for a mask. “I really was always a bit more comfortable as the Wizard of Oz kind of figure.” Electroacoustic music attracts him because the roles of composer, performer, and sound engineer overlap. “I’m not a great musician. I’m more of a noodler. Once I exhaust the idea, or I see everything I could do from it, I move on.”

In January, he returned to Nunavut to mentor young musicians for Ilinniq, a television series produced by longtime collaborator and throat singer Sylvia Cloutier. In the Arctic he sought opportunities to listen for ideas to use in Beyond Ice, a Canadian Museum of Nature exhibition for which he would coproduce and compose. How to translate ice? “What I do is just . . . I reflect. I’m a reflection. I bring a reflection of where I am and who I am and what I’ve experienced—but through music and sound. It’s an abstraction, beyond our normal language.”

Beyond Ice opened in Ottawa in June 2017. In one room, atmospheric drumbeats play as you walk past a row of refrigerated panels that mimic tundra ice. Inutiq couldn’t attend the opening. He was on the road, working as a projectionist from April to November, to take, as he says, “a step back from having to do something creative.” He drives an RV from west to east across Canada for Wapikoni Mobile, screening films made by Indigenous artists. The patriotic brouhaha of Canada 150 and Montreal 375 brings him “a lot of requests to work in a sociopolitical context—like a celebration of Canada or a celebration of Indigenous peoples. To have to work in more conventional venues has been quite the challenge, because I never really thought to consider myself as someone who could represent a wholesome image of municipal, provincial, and federal governments.” It’s no coincidence that Inutiq chose 2017 to escape the city and tour Indigenous communities.

In August, he calls me from the shores of Lake Huron. He’s in Ontario’s Pinery Provincial Park. Yesterday’s show was in the Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point reserve. He sighs, grateful for the opportunity to “take a pause, reflect, and take a look back at what I’ve been doing and to get some new experiences. What we do outside of music inspires what we do when we make music.” But then he tells me that he spent a night “jamming with the movies” on the ukulele with Jocelyn Piirainen, his partner and fellow projectionist. Piirainen strums, he plucks. When he’s out of earshot, Piirainen confides that he’s been working on “his music too, a little beat here and there. He just does a lot of experimenting on this trip.”

Music seems inescapable for Inutiq. He tells me how, emerging from Lake Huron after a swim, water dripping down his body, he heard “running water and birds and the sound of the leaves from the trees.” He pulled out his cell phone to hit “Record”—“impressed by the sound of the waves at the great lakes.”

Inutiq’s parents learned about Geronimo, the legendary Apache leader, while travelling as a young couple in the United States. His mother, Leah Inutiq, is a residential school survivor. Her father, Alooloo Inutiq, had the choice to have a Christian name or to keep his traditional name. He decided to keep his traditional name. “There was this will to keep Indigenous traditions alive,” Inutiq says, “and I think that having been given the name Geronimo is a reflection of that.” Artworks by both Alooloo Inutiq, a carver and illustrator, and Geronimo’s father Michel Bussières, a Québécois painter, are held in the collections of the National Gallery. Inutiq’s parents ran a print shop in Clyde River, 750 kilometres north of Iqaluit, where the sun doesn’t set for three and a half months each year. “I come from an artistic family, where visual arts and carving were very much present, so it wasn’t a stretch for me to get into the arts.”

As a child, Inutiq immersed himself in the outdoors, ancestral customs, and the futuristic. For amusement, he ran under the midnight sun, gathered roots and seaweed, ate berries until purple juice dribbled down his cheeks, played Inuktitut baseball with a stick and rock, listened to old legends and songs, and read H. P. Lovecraft and other fantasy authors, sci-fi, and comic books (his mother started calling him Superman). The Arctic “is a breathtaking place to be from, and to have been close to that nature [while] young—it really helped me to be who I am. I’m really grateful to be able to have learnt my mother tongue, Inuktitut, to have lived out on the land and been close to the lifestyle of the traditional way of the Inuit peoples.”

One day, he found some cassette tapes from Greenland. Unlike the “country-and-western kind of style that we had up in the eastern Arctic in Canada, [labels like Ulo were] producing Inuktitut music, but heavy metal or different kinds of contemporary styles of music.” When his mother, a CBC news reporter, brought him to the studio in Iqaluit or Montreal—where they lived in 1984—he waited for her and listened to records. In 1989 he moved to Quebec City, where his father returned after separating from his mother.

“I’m in three worlds in a way,” states Inutiq, who grew up singing “O Canada” in school every morning in Inuktitut, French, and English. “I’m part of the Inuit community. I’m part of the French-Canadian community. I’m none of that as well. That allows me to be original.”

In Quebec City, he played his grandmother’s piano and his grandfather played Québécois folk songs on the accordion. Inutiq also learned alto saxophone at St. Patrick’s High School. In the summer, his father took him to a powwow and to New York City, where the “streets smelled like piss” and he discovered Laurie Anderson’s “O Superman” music video at the Museum of Modern Art. In the house, his father began to keep instruments—guitars, synthesizers, sequencers, a drum machine. Inutiq fell in love with hip-hop and soon made friends at the local basketball court who loved it as well. He boasted to them that he could DJ. Soleyman, his new friend from Senegal, started calling him the “The Mad Eskimo” and introduced him to African percussion. They started a rap group, Presha Pack, that sold out fifty copies of a self-recorded cassette and booked gigs in any venue that would have them, from nightclubs to community halls. By seventeen, Geronimo was lying about his age to get a job spinning R&B at Tropikana, an African bar. He learned to DJ by tinkering. “I would try to match the records beat to beat by ear, playing with the pitch on the record. And then I would record one song on two tracks of the four-track cassette, I’d record that, rewind that, and then I’d take another record and then I’d try to match it on top of that using the other two tracks.”

At ease in three cultures, Inutiq also inhabits three musical roles. “In the traditional days of songwriting you had someone who was able to come up with the melody and sing it really well, you had someone who was able to record that and mix it properly, and then you had someone who had the job of playing it back on the radio. All that is mixed up into what I do.”

At age twenty, Inutiq moved to Montreal to study anthropology and sociology at Concordia University. He had a son. Deciding to move beyond the more unsavoury themes of gangster rap, he started making solo pieces on his computer in his spare time. He learned software programs like Ableton by watching online tutorials and started sharing his music on mp3.com and Myspace. Living on his own wasn’t always easy. He worked shift to shift, sometimes sleeping couch to couch.

Ironically, living at a distance from the North allowed him to access it through music. Sylvia Cloutier, a good friend of his sister, commissioned Inutiq to compose music for a radio commercial. What could you do with my throat singing? she asked him. This led Inutiq to his trademark sound: he infuses the melodies of his youth with urban beats. He began by remixing Cloutier’s throat songs into his soundscapes. Before A Tribe Called Red popularized powwow-step, the genre mixing electronic and Indigenous dance music, Inutiq released Developments (2008). On the album, Cloutier’s vocals ring over the beat of the qilauti, an Inuit drum, patterned over dubstep beats. “When we work together we feed off each other,” says Cloutier, who’s collaborated with Tafelmusik and Cirque du Soleil. “He’s the talented Inuk music composer that I know.”

In 2008 Inutiq also recorded Tagralik Partridge while they were sitting in his apartment, “riffing off some throat singing and improvised beats,” when Partridge suddenly broke out in rhyme. The result, These Apples, was broadcast on the CBC and performed at the McCord Museum in Montreal. For the recording, Inutiq layered Partridge’s spoken-word piece over ambient music that he composed. That year he started VJing. While on tour with the Algonquin rapper Samian, Inutiq projected films produced by Wapikoni Mobile. Applying sampling and mashup techniques to video felt like a natural progression. Inutiq searched archives for terms like “Inuit” or “Native American,” much as he rifled through records at the neighbourhood music store, then manipulated what he found. He set These Apples to an archival film about a Navajo family, which he digitally processed into glitch art. Soon, his experimental video-art caught the attention of curators, and Inutiq has since been commissioned to create films, prints, paintings, and photography. Surprise, surrealism, and a tongue-in-cheek attitude bridge his work across multiple disciplines, as does music, which often functions as the anchor of a piece. For example, voyage + variations sets film footage of Quebec’s La Vérendrye wildlife reserve to remixed Baroque compositions by Orlando Gibbons, Michel Corrette, and J. S. Bach.

By 2015, Inutiq was exhibiting a solo show across Canada, ARCTICNOISE. The multimedia installation re-appropriates Glenn Gould’s 1967 radio documentary The Idea of North, where Gould interviewed southerners who exoticize the North as an empty land. Inutiq splices Gould’s documentary with new work, as well as found sound and found video footage from Isuma, an Inuit-owned film-production company—allowing those that live in the North to speak for themselves to the viewer about the effects of colonialism and climate change.

In 2016 he exhibited INDIAN ACTS, featuring Microsoft Paint-like digital art; composed music with classically trained cellist Cris Derksen, who has performed with Tanya Tagaq and Kanye West, for a dance piece named Tsekan that combines poetry and projections; presented ᐃᓱᒪᒋᓇᒍ - isumaginagu - don’t think anything of it, a solo show using montage, abstraction, and pop art; and released Cri, a work that features Indigenous syllabic writing, created in five days with Sébastien Aubin.

This year, while Inutiq was up north, his short film Winter premiered in Ottawa. It begins with a traditional Inuktitut song. Then, in voice-over, Inutiq introduces his origins—an integral first gesture in many Indigenous cultures that initiates a relationship with the listener. In Inuktitut, he names his parents; in French, his grandparents. Finally, he speaks in English of Winter—not the season, but a stranger that he encountered in Toronto, implying that webs of kinship extend beyond blood. “I met Winter one Sunday night while walking down Bloor. At least that’s what he said his name was.” Winter is part Anishinaabe, part Iroquois. Inutiq relates to Winter, a man “sitting in front of a grocery store, talking to everyone passing by, making people feel uncomfortable, making people laugh.”

Inutiq’s partner Jocelyn Piirainen, who grew up in Nunavut, tells me that audiences do find his work unsettling and funny. In particular, she says, Inuit find his work “very humorous” and “they do relate to it.” She explains that “if you ask somebody what Inuit art is, they would think of different carvings or paintings. His is very contemporary. He incorporates, mixes up, and plays around with Inuit icons like the caribou or arctic fox.”

Both these animals are transformed by pop-art colours in Inutiq’s newest work, Ensemble/Encore, Together/Again, Katimakainnarivugut. From June to October it occupied a whole room of In Search of Expo 67, a major exhibition at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal. The New York Times described Inutiq’s piece as “a trippy installation that commingles videos, prints and a Katimavik-inspired dance floor.” (Katimavik means meeting place in Inuktitut.) On a Friday afternoon, I tiptoe onto the black floor covered with concentric white squares. I sit on the white bench in the centre. From one corner drones Inutiq’s riff on a composition by Otto Joachim that was the original soundtrack to Expo 67’s Canada Pavilion. (The spirit of Expo fascinates Inutiq. Here was “a pinnacle of the possibilities of futurism and the potentiality of the nation-state as an agent of newfangled corporate and technological breakthroughs.”) A man and two young boys walk in. One child giggles at the videos. Another runs around us, following the white lines on the floor. After they leave, a young woman enters and stands by the speakers, shifts her weight from foot to foot. We stay silent for ten minutes, mesmerized.

In Montreal, Inutiq retreats to his home studio. There he is part foley artist, part sound designer. He follows his intuition when “mixing and matching sounds from the world,” then resamples his recordings, highlighting certain frequencies. “Instead of orchestrating brass and strings, it’s orchestrating a bass rumble with the sound of running water, matching that with the sound of cracking sea ice, even adding a bit of fire sound to give it this quality of richness,” so that “through the magic of production I’m able to hear what I wanted.” Digital editing doesn’t erase the natural world. You should always be able to hear “the raw sound of the place of where you are” instead of “the pristine environment of a studio.” For a National Film Board soundtrack, Inutiq recorded himself in his apartment, singing and playing the guitar, as sounds drifted up from the street below. For the song “Dedications,” Inutiq gathered sound from bells, coins, plates, and Lego blocks, then embroidered them into percussive loops.

Instead of pushing for a record deal, Inutiq uploads his work online. “My son, he didn’t always have a lot of esteem for the process of art and music,” Inutiq says, because “it doesn’t always bring a stability in terms of financial revenue. It’s really difficult and challenging to have to do all the management in terms of promotion and financial management.” Now his son is a teenager. “I try to share with him through music. But you know, he’s a teenager, and he’s into rap music. I was into rap music at his age. Today it’s not necessarily the kind of music I want to listen to.”

Lately, Inutiq has surprised himself by enjoying smooth jazz like “corny” Kenny G. Above all, he likes modular music: house and techno that capture the “mechanical pulse of the universe”; dark ambient, even new age; and styles like boom bap—“it’s really got a swing to it and it’s lo-fi”—and vapourwave, which uses pop music as found sound—“it’s kind of a new style of punk music: it goes against the convention of what the norm is in terms of the standards of industry.” Recently, Inutiq remixed Kelly Amaujaq Fraser’s cover of Rihanna’s “Diamonds” in Inuktitut.

“I am a little bit of a hack with my samplers,” he admits. “I take someone else’s recording and I pretend ownership over it somehow because I ran it through a sampler.” And he returns, forever drawn to what he calls other people’s ways of hearing. The ability to sift through music and quilt it into your own patchwork has never been more relevant. “We’re [living] in a time where there’s so much music and product and culture. We have everything at our fingertips with the digital age. Being able to sample the world around us and sample old recordings keeps us in discussion with the world and keeps us moving forward. To be able to use new sounds and old sounds and present sounds altogether is an indirect way of jamming with someone.” And it’s less intimidating than actually playing with other musicians.

He’s insecure about his grasp of basic rudimentary music theory and autodidact techniques, and likes to deflect attention from himself. He could never see himself as “the lead singer, a handsome individual that you look at and idolize.” Cloutier describes him as “this introverted guy. That comes out through his music. That’s maybe his connection to the world or people. He’s listening to the world and the people around him, and then it’s filtered through him, through the music that comes out back again, and he’s able to express himself that way.”

Inutiq agrees: “It’s not about me, it’s more about what’s coming out of the speaker.” He embraces mixed media because it allows him to share his work in a gallery instead of onstage. He has also started to adopt new aliases, having left behind madeskimo. On Christmas day in 2016, Inutiq released the first album from his independent record label. Indigene Audio publishes limited-edition cassette tapes featuring his collaborators and his new alter egos. He returned to the cassette-tape medium of his childhood, when he made mixtape after mixtape with his boombox, because he likes how magnetic tape brings distortion, compression, a warble. Each album has a story around it, told through the artwork—he chooses tapes in a rainbow of colours and uses textured labels and tinted cases. And every fiction allows him to avoid the discomfort of the spotlight. Aliases like saturn土星 are aliens from “an alternative space.” They don’t have “to live up to an idea of what it means to be an Indigenous person.” Destiny天分 proclaims: “I hear and I forget.” Private Getaway promises transport “into a fresh and exciting virtual reality of our future pasts.”

The futuristic can indirectly engage, by imagining alternatives. “Identity politics is a big part of what I do,” says Inutiq. “But at the same time, I just find it so loaded at times, and really what I’m trying to do is an aesthetic exploration of sounds or textures or colours.” Inutiq isn’t interested in being an Indigenous poster boy. Although he believes he challenges the status quo, he prefers to give space to other activists, just as a DJ elevates those whom he samples. “I don’t necessarily try to speak for a collective,” says Inutiq. “For me, music is a very personal expression, and it’s a reflection of who I am as an individual.

“There’s importance in keeping traditions alive,” he continues, “but I think it’s just as important to keep traditions relevant.” Often, discourse about Indigenous musicians applauds the fusion of old and new. An Inuk DJ! But it’s easy to miss the point. Inutiq explains that the attraction to relevance is traditional. “That sense of innovation and that sense of independence comes from my Inuit culture. My will to innovate and my will to do it independently is also a reflection of my Inuit values.”

The 2016 Grammy-nominated compilation Native North America (Vol. 1): Aboriginal Folk, Rock, and Country 1966–85 or this year’s award-winning documentary film Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked the World remind us that contemporary Indigenous music has never been an oxymoron. When Inutiq is said to “freshen” Indigenous sounds, he’s honouring its resilience. Cloutier reminds me that “he’s intuitive when it comes to creating music, and he’s also intuitive as an Inuk.” In his music, “you still have the energy of those traditional songs and original songs, but he’s recreating them in his own way.”

At midday on September 13, it is hot and cloudless. Inutiq parks the RV beside a festival stage on the Montreal waterfront. It’s the tenth anniversary of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Traditional singers are doing sound check. Seagulls fight over an Indian taco. When I meet Inutiq, he takes off his baseball cap and uses it to fan his sweaty head. Under an embroidered inukshuk it reads, “Iqaluit, Nunavut.” He bought it as a driving hat from the Iqaluit general store, and wants to show me the camo pattern of brown leaves and branches on the cap. “I think it’s funny,” he laughs. “Because there are no trees there!”

He invites me inside his tiny home on wheels. Clothes, trinkets, and crumpled balls of paper cover the counters and beige carpet. The dashboard holds plants, teddy bears, and a miniature Dr. Who phone booth. CDs and cassette tapes fill the crannies. I pull out Jukebox Hits, MuchDance 2001. Inutiq hoists himself above the front seats, legs dangling, to rummage through a cubbyhole. From there he shows me the sweetgrass he received as a gift and a blue felt mask with googly eyes that he crafted to attend the Governor General’s ball at Rideau Hall the previous week. Then he brings down his instruments: battery-operated synthesizers and sequencers, a drum machine. Inutiq lays out his mobile studio on the kitchen table. He’s been fiddling around with it all. After the tour he will lead a group of amateur and professional musicians through a three-month creation of “sound pieces, drawing on the ecology of the mountain” at the heart of Montreal: this coming winter, skaters will glide to the beat of this music at the summit’s outdoor rink, Beaver Lake.

Living in a cramped space has its benefits. If Inutiq has an idea, he can take a step from the shower to his keyboard; he can swivel from the stereo system to the door that opens out to the sounds of the outdoors. Music, art, and everyday life become permeable.

We recall how one day he called me from a Walmart parking lot, where he’d slept the night before. He had described to me the view, which the men and women pushing shopping carts had seemed to take no notice of: “I can see some trees and there’s birds. There's always a bit of nature in the industrial world. And when I'm in the natural world I always bring in a bit of the industry into that . . . It’s life in motion. We're constantly trying to take pictures of where we are and things like that. It’s great to be able to give ourselves times of contemplation and to listen, and from there get some influence, inspiration.”

Then he had returned to the RV. He told me that in there, he could “work in a way where I’m kind of separated . . . I feel like almost I’m in a spaceship in here.”