It’s quarter past midnight in late May 2008. Storm clouds loom but hold, on this surprisingly humid night. I open the garage, grab my bike and check my backpack: flashlight, five cans of beer, five-dollar donation, notepad and pen. I recheck the instructions I printed from an online forum: “Do not be seen entering the property, do not break shit—and if the cops show up, DO NOT mention the name 'Extermination Music Night.'” Satisfied I can figure out the directions en route, I mount my bike and begin my trek.

I’m heading north of the downtown core, past a big-box plaza and onto a dimly lit industrial road northwest of Toronto’s Junction neighbourhood. Flanked by slaughterhouses, the smell of rotting meat lingers long as I seek the entrance into Symes Waste Transfer Station, a three-storey building built in 1933 and, like the meat I smell, left to rot since being abandoned in the mid-1990s. Ahead of me a crowd of six or seven stroll through what looks like a gate. I follow them into a vast parking lot overgrown with weeds. I lock up, enter through a dark door and descend a staircase lit by tealight candles into a crowded basement. I crack a beer. Flashlights and cigarettes offer fuzzy glimpses of upturned lockers and petrifying work boots. The floor is strewn with attendance-record sheets and a muddied copy of Candy Girls; pinned to the wall, the 1978 Occupational Health and Safety Act.

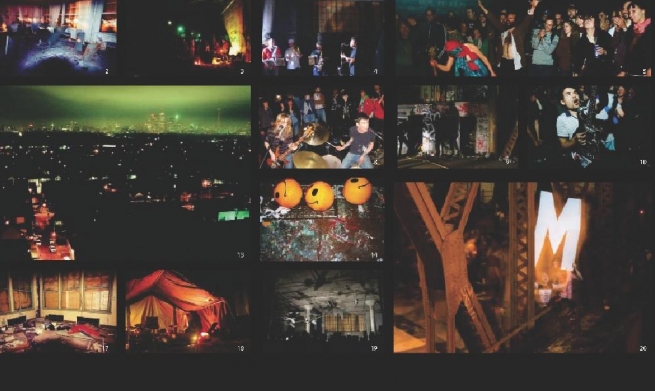

Upstairs, a sea of 600 people dance and cavort. Standing behind a makeshift bar (installation art, I later realize), Jubal Brown sets fire to a sugar cube dangling over a wineglass filled with green absinthe, which he sells for eight dollars a shot. The flames reflect in the puddles and broken glass lining the warehouse floor. Behind Brown, another installation, a fake record-retail outlet dubbed “Dad’s Records,” stocks dime-a-dozen LPs by James Last and other Goodwill icons. My eye catches the kaleidoscope, generator-powered projections by art collective Exploding Motor Car as I weave through a crowd of new faces toward the band. Set up in front of the light show, guitar-drums duo Tropics—Slim Twig and Simone TB—rip their way through a frenetic set. Standing mere steps from the encroaching audience, Twig, with his trademark pompadour and pencil-thin moustache, thrashes about, strangling his guitar neck with tremolo and walls of feedback punctuated by delayed vocals and sharp, deliberate drumming from Simone. The band, like the night itself, is charged with a surreal, carnivalesque quality.

No advertising, no security, no one passing out glossy pamphlets asking me to text my favourite band; no curfew, no rental permits or by-law permission asked for, let alone granted—conceptually and geographically we are miles from the galleries, clubs, and concert halls that define Toronto’s music scene.

“The whole idea of music being intertwined with bars is depressing,” says Extermination Music Night (EMN) co-curator Daniel Vila who, alongside Matthew McDonough, has organized more than twelve EMNs since the first show at the Don Valley Brickworks on Thanksgiving weekend, 2005. We’re sitting on a patio in Toronto’s bohemian Kensington Market. It’s been a year since the Symes Waste Transfer Station show, and since then Vila and McDonough have hosted five other EMNs, including a show six days ago inside a four-storey building once home to film titan Kodak. Unlike at Symes, the night was cut short by a police bust that saw several audience members and musicians issued trespassing tickets; as well, Vila and McDonough’s beloved generator was stolen. In light of this, I was expecting sour moods and talk of failure. Instead, the duo, both in their late twenties, are quite pleased with how things went, premature ending aside.

“Just because the cops came doesn’t make it a failure,” says McDonough, dressed neatly in a tie and sweater. “Getting busted from time to time is important; if it weren’t a possible outcome you wouldn’t have that small sense of danger in the air, the charged atmosphere that makes it such a special night.” Not that getting busted is the aim. By using the city’s geography and structures as a sonic landscape, dashing notions of what and where a venue is, an EMN offers an alternative way to experience music—an alternative that can’t be replicated in a concert hall.

“Our primary goal is to recontextualize music performance,” says Vila, sipping a beer. “There’s a sense of strangeness: you’re hearing music at an unusual time in an unusual place,” continues McDonough. We’re reminiscing about the first EMN, at the Brickworks. At the end of the night, after all the bands had played inside, electronics trio Awesome set up behind the building. “They were standing on some sort of sundial, like you’d see at a Greek theatre,” says McDonough, “forming a big smile that makes him look like an especially mischievous Matt Damon. “They were dressed in green robes and wearing round, battery-powered lights trained on their faces. The sun was coming up and they’d built a large wooden tepee and set [it] on fire.” While one of them tended the fire—creating crackling sounds as from a percussion instrument—the rest of the band sang drones over boom-box recordings. “It all came together so perfectly—the sound, the scene. You’d never get that in a bar.”

Since that show, more than sixty musicians and other artists (EMN mixes sound, performance, and visual art) in unlikely spots including abandoned factories once home to Buns Master bakery, plastics manufacturer Winpak Technologies, and Kodak; under bridges including suicide hot-spot the Prince Edward Viaduct; in a park, on a beach, and on an island underneath a train bridge. In each case, Vila and McDonough scout the sites weeks in advance. “When we visit a space, we’re always thinking about who would sound good there,” says Vila.

Organizing shows with multiple bands and performances is one thing; doing it in an illegal spot, with power supplied by a gas generator, in the middle of the night, in spaces with erratic acoustics and other obstacles, is another. “It’s the feeling that anything can happen,” says Jon McCurley, whose band, Rozasia, has played two EMNs. “The sound could turn on you, distort or echo in an instant, the cops could show up, the power could go out,” he says, recounting a performance at EMN II by Toronto punk band Anagram: “The lights went out and suddenly the entire crowd formed an impromptu light show with their flashlights. All you could see were red flashes and flying dust.”

But while the dust dazzled visually, other performers weren’t so pleased. “I was blowing black shit out of my nose during our set,” says reeds player Jeremy Strachan, who performed that night with his free-jazz, buckets-and-woodwinds outfit Feuermusik. Even still, stresses Strachan, the performance, along with the myriad other EMNs he’s since played at, was worth it. “Without a doubt, these shows have been career highlights for me,” he says. “There’s the slight fright that the whole thing could come crashing down at any moment, so every tune is essential and the playing is very intense.”

A typical EMN set runs thirty minutes maximum, with no warm up, sound check or preparation, other than getting to the venue itself—“I’m always downgrading my gear cases for better portability,” says Strachan. Besides Feuermusik, which features Strachan alongside drummer Gus Weinkauf, Strachan has also performed EMN nights with Canaille, an acoustic quintet that sounds at first like straightforward jazz (steady, precise rhythm with soloing horns) and slowly builds to something a little more “out there,” says Strachan.

During last summer’s Canaille set under the Prince Edward Viaduct, a venue better known as a suicide bridge than a music venue, the crowd wrapped itself tightly under the arches and around the band as they created bright, melody-based numbers spliced with overlapping soloing and the occasional free-jazz freakout. With no stage barrier, the audience stood steps from drummer Brandon Valdivia, nearly knocking over his kit while the rest of the band, including sax player Colin Fisher, played on, punctuating noise created by passing trains above, a perfect counterpoint that was both disorienting and climactic.

“With improv and jazz music, you tend to see the same faces wherever you play—often other musicians,” says Fisher. “It becomes insular and boring, but at Extermination, you see new faces—not just partying but actually listening. I mean, here we are playing hard-bop–influenced free jazz and all these young kids are screaming.”

Because EMNs take place in public or abandoned space, where there’s no club owner or, in the case of private house shows, no homeowner, there’s no elitism with EMNs. “We’re not exclusive,” says McDonough. “We like that there are strangers at our shows, people we don’t know coming out to experience something new, people that wouldn’t go [to a club to] see bands they’d never heard of, … but do so here.”

“That’s what’s so great about Extermination: it disarms the performer and the audience,” adds Valdivia. “Cultural tropes are eliminated because nobody has any expectations other than an expectation to hear and see something new in a place they’ve likely never been. There’s no elitism. And for bands, it means we can try new things and create new ensembles for the night and experiment with sound.”

Unlike the situation in a jazz club, where there’s weight behind its status in the jazz community and performers are expected to play a certain way—and the audience is expected to act like “jazz fans”—EMN adopts a more adventurous attitude to sound. After all, where else can you hear Christine Duncan’s thirty-person-strong Element Choir followed by artists including one-man hip-hopper Onakabazien. Rather than fitting into a mould, McDonough and Vila curate, in the loosest sense of the term, based on who they think will sound good in the space. “Unfortunately, quiet music doesn’t tend to work here,” says Vila. Instead of themes, there’s an overriding intention to create an interesting night, where the night itself becomes the motif.

“There are no set times like at a regular group show,” adds McDonough. “EMN starts when the sun goes down and ends when the sun comes up. It’s the entirety of the music, the sounds around you, the art, the building—not one single component.” Ambient or unexpected noises abound at these shows. At EMN IX under the Old Eastern Avenue bridge below the Don Valley Parkway, Fisher and Valdivia’s band Not The Wind, Not The Flag played while cars whizzed by and, above them, a police R.I.D.E. program was in effect. “We were tucked in under the bridge, playing as loud as we could,” says Valdivia. The combination actually created a sense of calm in the audience, with the drums and sax almost blurring into the sound from passing cars into a wall of white noise.

Ambient noise, the space itself, the crowd and the other players all factor into what a band will play and how it will sound. “We arrive, talk a bit, see who else is playing and whether we want to contrast or go along with a vibe,” says Fisher. At the Kodak show, the room was essentially a large gymnasium nestled inside a decrepit building strewn with falling debris, and the sound was immense: a simple drum tap would reverberate and bounce around the room with thunderous timbre. Because of this, plus the fact that black metal band Orn was also on the bill, “Dan and Matt suggested we stay away from any ‘hippy bullshit,’” says Fisher, who played an extremely brief set that night as part of No White God.

Seeds were planted years earlier

Extermination Music Night, like most other live music scenes, didn’t just spring to life on its own in a “Eureka!” moment. Techno DJs have long occupied abandoned warehouses and, in the case of more experimental-minded art communities, music has been performed on the spot in odd places for decades, the most obvious example being the Happenings of John Cage and other Fluxus artists in the early 1960s. Still, these EMNs are exceptions to the norm, especially in a city such as Toronto where music is largely the domain of concert halls and sanitized beer-or bank-sponsored festivals where art, like the overpriced draught, is swallowed in large, once-a-year gulps.

In the late 1990s, McDonough discovered Calgary was home to an underground multidisciplinary arts scene which mixed installation art with sound. “They were free, and people could just show up and perform,” says McDonough, who moved to Toronto from Calgary in 2000 and soon discovered a likeminded scene. Playing in the punk band The Creeping Nobodies, McDonough soon met Vila, who also played in a band, No Dynamics, when Vila threw a show at Cinecycle, an old coach house turned into a bike shop and film-and-performance space in a back alley off Spadina Avenue. It was after this show that the two came together and began planning EMN. But while the first EMN took place in 2005, the seeds were planted years earlier, in the late 1990s, when a then eighteen-year-old Vila, who’d recently moved to Toronto from Barcelona (he grew up in northern British Columbia) attended an event billed as Wasteland. “Wasteland had this sense of quest that began as soon as you left home,” says Vila, fondly. “Difficulty was very important: difficulty finding out about the event, difficulty finding the actual venue, difficulty accessing it—it’s what made it so satisfying.”

Similar to EMN but with a larger focus on performance and installation art, with less emphasis on music, Wasteland was radicalism manifest, as was its main curator, Jubal Brown, who gained notoriety while still a student at Ontario College of Art and Design for spewing red goo on Raoul Dufy’s painting Harbour At Le Havre, at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

“Wasteland was outrageous: the danger, the underlying currents of sex and violence; fire was always really big, plus Bacchanal aspects like booze and feasts,” says a co-organizer, Daniel Borins, himself a well-known artist with work hung at the National Gallery. “The night itself was an art form.”

In an interview titled “Life Is Pornography,” published in the book Practical Dreamers, Brown explains one of the primary goals of Wasteland, eliminating the entrenched relationship between audience and performer, artist and viewer: “It was a beautifully naive attempt to give something real … to engage with others in an environment free of any of those stigmas … We took people back to the cave, and together we burned, we bled, we feasted, we indulged in pleasures and pains, we were alive for a moment or two. It was the only good thing I’ve ever done.”

For two or three years, Wasteland events took place in abandoned abattoirs, inside a clock tower, in the basement of a ditched church and at the Brickworks. For both audience and performer, says Vila, “there was this sense of traveling, like you’ve left the city and landed somewhere else for the night.”

Exoticizising the local is something EMN, like its predecessor, Wasteland, does especially well, as witnessed by anyone present at EMN XII, which took place on a muddy beach under a train-trestle-bridge beside the Don River. Reaching this “island” required following a path into the woods and hopping a stream. Seemingly surrounded by water, but with the city’s urban skyline visible through trees, it felt foreign, like being in another city in another country. (“Welcome to Miami,” I remember thinking.)

Singular but not alone

These days, while there’s nothing else going on quite like EMN—in Toronto, at least—there are other artists doing smaller-scale shows in non-traditional spaces. Two summers ago, McCurley arranged a performance-art show at an abandoned nunnery in Toronto, with 30 artists carrying out hour-long looping plays. The audience met at a nearby house before marching single-file into the nunnery. “It must have looked odd seeing 200 people walking silently down a street and then suddenly they all disappear,” he says. To avoid detection, there were no lights inside the nunnery, and only the sound of whispers. “You could hear the neighbours next door doing their dishes.”

As for music, Torontonian Matt Cully—member of large improv ensemble Bruce Peninsula—curates the yearly Poor Pilgrim festival on Toronto Island. Here, the audience–performer divide is erased; bands set up across the island, seemingly haphazardly, on park benches, in wooded clearings and near the docks. Members of the audience meander across the island, encountering sound as they go, beginning with the ferry ride from the mainland. In 2008, tourists became audience when Heavy Water (Wolfgang Nessel) performed for ferry passengers. Nessel ran samples through a looping pedal, creating a gentle, cyclical soundscape that, like the waves passing below, rose and fell in gentle steps.

Free improv, jazz, drone, psych-folk, noise: like EMN, Poor Pilgrim refuses to pin down its sound or location. Instead, its aim is much broader: to connect the music of the city with the city’s fabric—its architecture, streets, and parks, its spaces and people. “You walk into an art gallery and it’s a sterile white box,” says Jason Van Eyk, Ontario Regional Director of the Canadian Music Centre. Unlike the CMC’s New Music in New Places program, “The work is intellectualized because the space is intellectualized, so you get a rote response and a tired audience.” But, he says, change the way it’s presented and people forget what they’re seeing or hearing. After all, millions of people stay up all night viewing (supposedly dreaded) installation art each fall at Nuit Blanche in Toronto—because the art is hung outside the gallery.

The New Music In New Places program isn’t just about finding a new audience, but also about finding performance spaces that suit the works themselves. “Not all music suits the concert hall,” says Van Eyk. For example, when Hamilton-based composer Christien Ledroit composed Tradewinds, he had the Hamilton Go train station in mind. “The work features a violinist and a tabla player, so it’s this East-meets-West, Western-classical-crosses-paths-with-Indian-[classical]-music composition,” explains Van Eyk. “In a train station, people constantly cross paths with one another, moving in opposite directions without really coming together, making it the perfect venue to perform Tradewinds.”

What is the music of the city? How does it sound, and where does it take place? These are questions that beguile Toronto architect David Lieberman, who teaches at the universities of Toronto and Waterloo. Alongside Daniel Cooper, Lieberman put together the soundAxis festival in 2006 and 2008. Partly inspired by twentieth-century Greek composer Iannis Xenakis (Lieberman wrote the forward to Music and Architecture, by Iannis Xenakis and Sharon Kanach), soundAxis was about testing the potentiality of the city’s spaces, not just as vessels for performance but as active components of it.

“Open up a book on architecture and you see designer furniture but no people. Buildings are seen as objects, but they’re not. They’re experiences, and how you occupy the space is just as important as its shape, or the materials used to build it.” He’s trying to explain “performity,” an architecture term capturing a space’s ability to participate both in the production of and engagement of its use. Performity, he says, “is more than materials and structure; it is emotive character of the space, and this includes sound.”

When it comes to emotive space in Toronto, few, if any, can beat the vibe of the Prince Edward Viaduct and its Luminous Veil suicide barrier that, from below, looks like a giant stringed instrument. When Vila and McDonough were planning EMN X, they asked sound sculptor Joda Clement if he’d like to play—the bridge, that is. Taking input from passing trains and other ambient sounds and feeding it back through a processor, Clement improvised a slow-moving wall of sound with sudden explosions whenever a train passed. This type of site-specific improv can be heard on his Cherry Beach recording. “For the other performers, the trains were a hinderance; to me, they were integral to my piece. Every time a train went by it was like a bomb went off. I was very pleased about that.”

Clement, like his idol, Spanish sound artist Francisco López, plays his surroundings by capturing from nature sound that couldn’t otherwise be heard. “Phonography and photography are similar in that they are both representations of reality,” says Clement. “You’re better off going to the woods than listening to a representational recording of the woods, but if you can reveal something else, a naturally occurring sound that doesn’t have an obvious origin, such as feedback created by wind blowing grass onto a contact mike, you’re creating something new.”

At EMN X, Clement and Anna Maria Didur created a sound installation that explored the separation between spectator and spectacle, audience and performer, using two feedback loops that could be manipulated by the audience and the immediate environment. The first feedback loop was created by hanging a miked violin from the ceiling using fishing line. The output level from the contact mike that was attached to the violin strings over the sound holes was adjusted to rest on the threshold of a feedback loop. In addition to this setup, they added a tape cassette recorder with an internal speaker and microphone for the second feedback loop. “I put a wineglass on the table just to show how you could manipulate the sound,” says Clement. “People could grasp what I was doing and were very interested—something that doesn’t normally happen with sound art and general audiences.”

Vila and McDonough begin their search for venues online, through photo blogs and message boards frequented by urban explorers and paranoia believers. But while they share a common interest—exploring decaying, abandoned structures—the similarities quickly erode. “I hate the paranoia people as much as I hate the urban explorers,” says Vila, his face expressing annoyance. “They have this fundamentalist code: take only pictures and don’t disturb the building. We’re coming to these spaces from the opposite point of view. Our minds are always focused on doing something with the space.”

While such controlled chaos in unknown buildings leads to inspired performances, it also creates special challenges for the two curators, beginning with the (since stolen) gas-powered generator that sputtered to a stop around midnight during EMN XI. “We ran out of gas,” says Vila, sheepishly, an understandable tone, considering the more than 700 people in attendance. “We felt really stupid about that.” Before each show, the two of them spend time securing doorways and sweeping broken glass. On the eve of EMN X, Vila went over to sweep up the glass. It was 9 p.m., and in came three cops, randomly. “I rambled something about being here to take photos but I only had my cell phone. They searched my bag and found a hacksaw for cutting the gate lock.” The cops took his info and let him go but the scare remained. With the show a day away, would the cops return?

“It’s very hectic during the show,” says McDonough. Not only are he and Vila organizing upwards of twenty musicians, helping install art, and fiddling with loudspeakers, but they’re also dealing with unexpected problems that would never occur in a bar. “There was a schizophrenic walking around at Kodak, upstairs near a doorway we’d locked that led into an elevator shaft,” says McDonough. “We had to drop what we were doing and slowly coax him away from the door and back downstairs or he might have fallen down the shaft.”

It’s been a year since my first sojourn into EMN at the Symes building. After a long winter, spring has sprung, and with it, more journeys into the city’s wastelands. Tonight I’m inside what’s left of the near-demolished Kodak film plant along with seven hundred other people. It’s early, half-past midnight, when I enter through a side door, drop a few bills into a bucket and stroll past the first installation, a timely taco-stand and swine-flu clinic. Broken drywall is scattered everywhere. Nearby, an incredibly bright room is dressed to look like an office (two desks, scheduling clipboards pinned to the wall, a coffee maker and filing cabinets) complete with “Kodak employees.” Another room has two stuffed bodies lying on the floor that, for a second, trick me: dead bodies—no way! I make my way up a flight of stairs into a large gymnasium and crack a beer. At the far end, just below a curtained stage, sit stacks of amps, instruments, wires, and pedals. In the midst of the chaos, Carl Didur is midway through his Terry Riley–sounding set. Using synthesizers, reel-to-reels, and tape loops, the droning vibes are a nice contrast to the smashed-apart building.

Nearby, black-metal band Orn stand together, carefully eyeing their equipment and the crowd. In the middle, drummer Justin Smith looks my way, his white face giving away his sense of fright. (“I was living my worst nightmare that night,” Smith revealed to me a few weeks later outside a Michael Gira show.) Upstairs, under a small tent, a girl reads Sylvia Plath under the glow of a flashlight. I sit with her for a bit, sipping my beer. Just past her, a door opens and I walk into a one-woman monologue. Wearing a prom dress, she’s standing behind a small wooden table and holding a large chef’s knife, which she uses to cut oranges as she talks in vague language about “moving on.” I eat a juicy slice and leave. A few rooms over, a shirtless man is decrying a failed relationship. Like everything else, it’s staged; a mock encounter straight out of The Magus.

After slowly exploring the vast basement, complete with still-sealed WordPerfect booklets and whiteboards scrawled with graffiti, I make my way back to the gym. We’ve been waiting patiently for the music to start. Near the stage but not on it, No White God is set to play. Sax in hand, Colin Fisher stands, his cell phone ringing. The cops are outside, he’s told. Hit it!

For two full minutes, I delight in a caustic brew of skronking sax mixed with a relentless drum solo. The crowd goes insane as a man masked in an orange balaclava whips chains against cymbals spread along the floor. Electric guitar scorches through the amps. Then the power cuts and the doors smash open to an army of blue-suited cops. Drummer Matt “Doc” Dunn keeps the beat as cops walk out of the shadows and move together like precision skaters. A cop throws Smith to the ground and it’s over. Talk about a finale.

Audio: Good Bits (2009). Composed by Jeremy Strachan. Performed by Jeremy Strachan, alto and tenor saxophone; Nicolas Buligan, trumpet; Michael Smith, bass; Dan Gaucher, drums. Images: Adam Cowan (2), David Walden (3, 5), Stef Hardman (4, 18, 19), Patrick Fisher (13, 20), Connie Tsang (14).