Festival de International Musique Actuelle de Victoriaville (FIMAV) has defined itself by diversity, crossing genres to present fresh, unexpected music, whether intimate or epic, and maintaining a tradition that touches on classical, pop, and jazz. The festival is a major event, mounting twenty-one performances in four days, with concerts starting as early as one p.m. and ending at two a.m. This year, the final day alone ranged from Quebec guitarist Tim Brady presenting an orchestral work inspired by Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony to the Nels Cline Four playing virtuoso interpretations of jazz compositions by Carla Bley and Paul Motian.

That specific diversity was apparent in three projects that involved saxophonist Colin Stetson, this year’s most frequent performer. His work Sorrow: A Reimagining of Gorecki's 3rd Symphony has roots in an oversized representation of emotion: in the hands of the circular- and fire-breathing saxophonist it expanded exponentially, with mandolin-like tremolo chords from two electric guitars, rock-heavy drumming, and his own weighty sound on bass saxophone underpinning it all, suggesting Wagner in the Jurassic period.

The next night, Stetson appeared with the industrial-strength rock band Ex Eye, then a day later contributed his gargantuan sound to the conclusion of another epic work, trumpeter Nate Wooley’s fifth version of his expanding, highly improvisatory Seven Storey Mountain, here presented by a group of nineteen musicians. The work is also about continuously expanding sound, beginning in relative quiet with tapes, strings, and percussion, and gradually reaching a torrential level with a brass ensemble, electronics, and the low-register roar of tuba, bass saxophone, and contrabass clarinet, a sustained crescendo that testified to Wooley’s creative energy and imagination.

Tradition is a living presence at FIMAV. Complementing performers like Wooley, who was here for the first time, were Anthony Braxton, who first appeared in 1986, Gordon Monahan (1987) and Terry Riley (1988). Each demonstrated his continued vitality and relevance. Appearing in the final concert, the seventy-one-year-old Braxton played solo saxophone for seventy minutes, a titanic performance that moved from machine-gun bursts to airy harmonics, whether welded to his own structures or lightly tethered to the chord changes of ancient American songs.

Monahan composed and performed the festival’s opening work, Dollhouse, a collaboration with dancer-choreographer Bill Coleman (LEFT), in which a Pee-wee’s Playhouse of sculptural creations aided in performing Monahan’s music, as Coleman created a series of dances in which he seemed at war with his body and his environment, from awkward movements that triggered brittle cracking noises to flailing about in a jacket pierced with arrows. Somehow it was funny.

Terry Riley and his son, guitarist Gyan Riley, emphasized music’s modal underpinnings, beginning with Riley senior singing a raga with precise microtonal control, then gradually shifting from piano to melodica to a synthesizer that sounded very much like a Japanese sho. It invoked a kind of pure music-making, two musicians building pieces out of fundamental materials that stretched to touch on specific details from Asia, Ireland, and the blues.

Those nuances were amplified in the festival’s global diversity. German improvisers Gunda Gottschalk and Ute Völker appeared with the three Mongolian Samdandamba sisters (RIGHT), who performed whimsical, engaging (and, of course, incomprehensible) songs and stories in traditional costumes and makeup. At the opposite pole—visceral intensity—was Senyawa, the Indonesian duo of singer Rully Shabara and Wukir Suryadi, who bows, plucks, and strums homemade string instruments fabricated from bamboo and metal, heavily amplified with effects pedals. Their songs explode with the energy and brevity of punk rock; Shabara’s vocal range seems somewhat wider than Yma Sumac’s, leaping higher and lower in strange duets with himself; there’s a shamanism here that speaks of possession, transformation and healing, a trans-species power that at one point suggests the bleating of a sheep discovering sheep Hell, at another a furious incantation. At times Suryadi bows his delicate-looking instrument with demonic energy; at others, he pounds out rhythm guitar with the force of Bo Diddley. By the conclusion of their set, they’re still mixing languages and smashing idioms.

FIMAV is still finding new venues as well as new music. This year the day’s opening concerts took place in Église Saint-Christophe-d'Arthabaska, a richly resonant church that proved an ideal setting for an all-acoustic series, a perfect start to a day of listening. The first group to perform was In the Sea, a string trio made up of American-born, Amsterdam-resident cellist Tristan Honsinger along with Québecois violinist Joshua Zubot and bassist Nic Caloia. It’s a real band: they’ve just released a CD (Relative Pitch) drawn from an extended tour, and were embarking on another. Honsinger’s compositions, brief melodies with still shorter lyrics, invoke a vital folk tradition and create a communal space. Zubot’s lively, sometimes flamboyant runs bounce excitedly off Honsinger’s off-kilter punctuations and Caloia’s solid foundation.

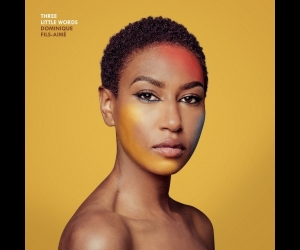

The next day Battle Trance (TOP PHOTO), not just a saxophone quartet but one that’s all tenors and yet somehow subtle, engaged the church’s lively acoustics. Eschewing solos, the band employed contemplative silences as well as humming, whistling, and singing into their horns, playing with the room’s resonance with interlocking, overlapping phrases while touching on flute-like highs and breathy low pitches.

The ultimate exploration of the church’s sonic possibilities came with Jean-Luc Guionnet. Best known as a saxophonist (Hubbub, Ames Room), he played the church’s pipe organ, exploring the resources of its stops, bellows, and pedal possibilities to create rumbling lows, beat patterns, and sustained sound in which the building became an equal partner in the creation.

FIMAV continues to expand in other ways as well, exploring new media as well as new spaces. This year saw the introduction of music-related film screenings, along with an increasing presence of video and dance in the concert programming. This was the eighth year for sound installations, an expanding program that engages the local community, including school groups, in creative interaction with sound. It’s a spirit of discovery that makes FIMAV an essential festival, still doing what it started thirty-four years ago.

All FIMAV 2017 photos by: Martin Morissette