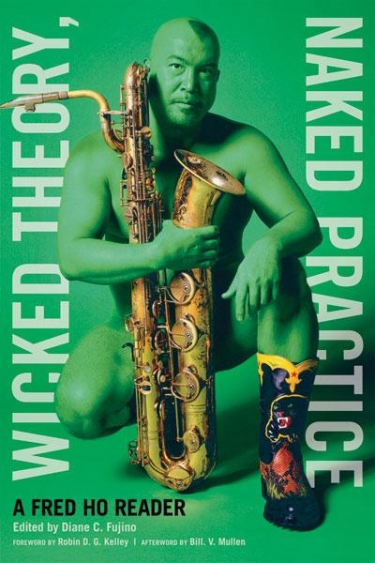

Composer, bandleader and baritone saxophonist; theorist; revolutionary socialist, and Black-Asian-American, Fred Ho writes essays that are as uncompromising and defiant as his compositions.

This wide-ranging collection elucidates the evolution of his philosophy from 1984 to 2006, while tracing his development “From Banana to Third World Marxist”—as he terms it. Although his essays on the twists and turns of identity politics, as seen through the prism of dialectical materialism and Mao Zedong-styled Communism, may alienate readers interested in music, politics are his very fabric. As he states: “When people ask me how long I’ve been playing the saxophone, I tell them as long as I’ve been in the struggle. When activists ask me how long I’ve been in the movement, I tell them as long as I’ve been playing the saxophone.”

Born to an assimilated family in Amherst, Massachusetts, in 1957, Ho discovered improvised music when most students were interested in skin care and sports. By the age of twenty-five, he was a New York musician. His commitment to avant-garde jazz stemmed from his exposure to the charismatic tenor saxophonist and Black Nationalist-Socialist Archie Shepp, and to trumpeter Cal Massey, a Black Panther sympathizer whose Afro-centric compositions were recorded by major figures like John Coltrane. Some of Ho’s most perceptive writing is his analysis of the influential but little-known Massey, plus the roles of Shepp, poet Amiri Baraka, and other jazz-sympathetic figures of the 1970s Black Arts movement.

Central to Ho’s argument is his insistence that jazz is America’s true revolutionary music. “Every feature . . . is an expression of revolutionary dialectics. Demarcations are dissolved between soloist and ensemble; among melody, time and harmony; between composition and improvisation; between traditional and avant-garde; between artist and audience; . . . between Western and Eastern etc. Jazz involves the impulses to go to the people, speak to the people and change the people.”

From 1976 to 1989, Ho was a self-described “cadre” of I Wor Kun (IWK), an Asian Black Panthers counterpart, then in the League for Revolutionary Struggle (Marxist-Leninist), which united IWK, Chicano, and Black organizations, forming a Communist group with what Ho calls a majority “oppressed nationality membership.” After he researched folk traditions of Asian groups in the United States, Ho’s jazz bands consciously used Asian instruments alongside Western ones and played compositions based on earlier Asian-American music. Simultaneously, he created multimedia programs, including a martial-arts ballet and operas with titles such as Bound Feet and A Chinaman’s Chance. Consequently, his insider’s knowledge and jaundiced view of Asian-American improvised music is another of his substantive themes.

According to Ho, not only must music “. . . draw from or reflect aspects of traditional Asian music influences,” it must also “help catalyze . . . consciousness about our oppression and need to struggle for liberation.” Subsequently, although most committed Asian-American improvisers have avoided what Ho labels “chop-suey ‘fusion’ music . . . [with] cute koto frills, ceremonious Chinese gongs and parallel fifths thrown in for spice like MSG,” the majority of players reject politics. Although Ho was involved with these musicians and initially recorded for the Asian Improv (AI) label, their apolitical stance caused a rupture, and he charges that he has since been banished from AI’s history.

Non-mainstream musicians will be most interested in parts of Wicked Theory, Naked Practice that illustrate how a defiantly anti-establishment, transgressive, and ideological Marxist artist such as Ho manages to get his music before the public—how he sells, without selling out. Ho controls his own means of cultural production through Big Red Media (BRM), a production company of which he is sole owner, president, and chief executive artist. With collaborators who work part time on a commission basis, this guerilla enterprise is a “combination of a small business corporation and old-time Leftist collective.” Raising money through such strategies as grants, fundraisers, sales, and donations, BRM uses earned income to pay for new projects such as concerts and CDs, and covers Ho’s living expenses. With associates who are extremely committed and professional, and without a manager, BRM manages to be more profitable for Ho than if he were affiliated with a major record company. This strategy may be disingenuous, since Ho appears to have made the free enterprise system he fervently opposes work for him.

Furthermore, Ho’s hostility towards capitalism may have intensified since 2006, when he was diagnosed with cancer, despite monitoring his diet and exercising rigorously. Having twice undergone chemotherapy, he figures that cancer will only be vanquished when the toxicity associated with burgeoning capitalism is eliminated. One wishes him well, but the ghoulish irony remains that if this revolutionary socialist is silenced, it will result from the carcinogens created by the society he has fought against for so long.