Edited by Meg Sheppard.

One of the best contemporary music festivals I have attended took place in Buenos Aires from June 17–24, with symphonic concerts at the Belgrano Auditorium, and chamber music and electroacoustic music concerts at the Centro Cultural Borges. It was given the full name La Música en el Di Tella—resonancias de la modernidad—Homenaje al Centro Latinoamericano de Altos Estudios Musicales (CLAEM) en su 50o aniversario (Music at the Di Tella—resonances of modernity—homage to the Latin American Center of Advanced Musical Studios—CLAEM—on its fiftieth anniversary).

The CLAEM was the brainchild of renowned Argentine composer Alberto Ginastera. It was established in 1962 within the Di Tella Institute and was part of a complex that included music, experimental theatre, art exhibits, and new concepts in graphic design. It was funded by the Di Tella Foundation and the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations. Ten years later the complex was peremptorily shut down by a dictatorial government. Of CLAEM, José Luis Castiñeira de Dios, National Director for the Arts, wrote, “Ginastera’s project was not only ambitious but a new concept: to create in Argentina an international center for the teaching and promotion of the music of the XX century.” From 1963, every two years a cohort of twelve talented young composers from all over Latin America was chosen by an international jury. The fellowship lasted two years. Young composers had the chance to study with luminaries like Messiaen, Copland, Dallapiccola, Maderna, Ginastera, Davidovsky, Malipiero, Xenakis, Halffter, Nono, Ussachevsky, and others—what a roster of pedagogues! The CLAEM also had the most advanced electronic-music laboratory in South America. That laboratory is the only part of CLAEM still operational today, as LIPM (Laboratory of Information and Musical Production).

This year the CLAEM Festival brought to Buenos Aires thirty-two of the original fellows. They variously contributed pieces composed during their student years at the CLAEM and in recent years, with a total of forty-nine compositions performed in all, so it will be impossible to write in detail about each one. Complete details of programs, exhibits, and photographs can be found at <www.lamusicaenelditella.cultura.gob.ar>.

The first and last concerts had the National Symphony performing this novel repertoire. On the first night the large audience warmly applauded Elejia by composer Rafael Aponte Ledée (Puerto Rico) and Tartinía MCMLXX by Jorge Antunes (Brazil). The concluding symphonic concert also had solid writing and interesting sonorities in Estudios sinfónicos by Blas Emilio Atehortúa (Colombia), Música ritual by the Argentine Mariano Etkin, and—closing the festival—an iridescent work with a clear Andean feeling, Las transformaciones del agua y del fuego en las montañas by Alberto Villalpando (Bolivia). The guest conductors were Alejo Pérez from Argentina, Jorge Sarmientos from Guatemala (conducting his own work) and Alfredo Rugeles from Venezuela. As an encore, the orchestra performed the Malambo by Alberto Ginastera.

All the chamber music concerts at the Centro Cultural Borges were preceded by a “poliartistic experience” by American composer Francis Schwartz, assisted by actress-dancer Laura Lucacci. Engaging and full of surprising turns of events, Schwartz’ efforts wildly entertained his audience.

The compositions performed at the Borges were prepared and conducted by Marcelo Delgado from Argentina. His musicians were excellent professionals and Maestro Delgado proved himself both a dedicated conductor and an expert accordionist in a performance of Quodlibet IV by Gabriel Brncic (Chile/Spain). A very warm reception was given to Graciela Paraskevaídis (Argentina/Uruguay) for her work Magma for brass instruments, performed during Concert II. Concert III offered works that were composed half a century ago and that have kept their vitality, as proven by Cuarteto de cuerdas by Mesias Maiguashca (Ecuador/Germany) and Mística N. 5 for small ensemble by Alberto Villalpando (Bolivia). Concert IV premiered semios for piano and electroacoustic sounds, by this correspondent (Argentina/Canada) and Made in . . . for three or more participants, by Oscar Bazán (Argentina), then closed the evening with the intriguing Soles by Argentine Mariano Etkin.

One of the best works in the festival was by Coriún Aharonián (Uruguay), Una estrella, esta estrella, nuestra estrella for harpsichord, piano, bandoneón, guitar, double bass, and choir. It was textural, rich, and engaging.

This festival and the legacy of the CLAEM are solidly represented by electroacoustic music, but surprisingly, Concert VII, Obras electroacústicas, had the smallest audience. The limited quality of the audio system may have kept people away. The performances were of the highest level—from instrumentalists, singers, choir, soloists, and conductors. This was parallelled by the sustaining quality of compositions already forty or fifty years old.

The CLAEM Festival provided a well-printed and detailed concert program, plus a large, deluxe-edition commemorative book, with documents, photos, articles, and a detailed list of CLAEM professors, courses, plus bios of teachers and fellow students, photos of concert programs from 1963–1972, and documentation on eight international new music festivals that took place at the CLAEM.

There was also the launching of a book by Laura Novoa, Ginastera en el Instituto Di Tella: Correspondence 1958–1970, published by the National Library, a book that, among other things, researches and investigates the inception of the CLAEM. In the works are a double CD with the music performed at the festival and a DVD that will include interviews with all the fellows who attended, plus film footage of all their activities while in Buenos Aires. The film is directed by Andrés Di Tella.

At the Borges, the large area surrounding the two concert halls was dedicated to an exhibit about the CLAEM, organized by Universidad Maimonides. It included enlarged historical photos and documents, facsimiles of scores whose corresponding recorded music was triggered by a laser device when people stood in front, machines from the famous CLAEM electronic-music laboratory and other inventions by Fernando von Reichenbach, the genius behind the machines. Some sections had dedicated computers where the visitors could access historical interviews, view score pages or listen to compositions from the ’60s and ’70s. This exhibit, curated by Pablo Gianera and Hernán Gabriel Vazquez, was visited by thousands during the festival, and is to become a touring exhibition. All the concerts were sold out, with the one exception noted. A marvellous festival.

Of the many topics addressed at the round tables, let me single out one, which was titled with a question that I will answer: Qué quedó del CLAEM? (loosely translated, “What’s the legacy of CLAEM?” or “What did Claem achieve?”). Well, I believe that the CLAEM was the most influential music school in the Americas. Its graduates became renowned teachers, conductors, and composers in their own countries. As well, several taught for extended periods—or chose to reside permanently—in other countries, such as the USA, Canada, Germany, or Spain.

There is no space here to name all the numerous sponsors, institutes, and universities that cooperated in the realization of this magnificent festival. However, mention must be made of the Presidencia de la Nación and its Secretaria de Cultura, of the Direción Nacional de Artes with the splendid cooperation of José Luis Castiñeira de Dios, of the executive producer of the CLAEM Festival, Micaela Gurevich, and of Maestros Eduardo Kusnir and Gerardo Gandini, for the artistic direction and programming of the festival.

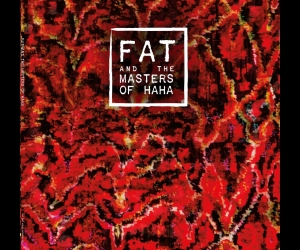

Image: Poster advertising the festival. Image courtesy of alcides lanza.