An endless stream of recordings flows through the Internet. Listeners rejoice in having easy access to over a century of music, their mood dampened only in contemplation of the terabytes of sound they will never find time to hear. Few, however, have stopped to study how this increased availability affects their perception of music history.

No audio recordings were available prior to Edison’s invention of the phonograph in 1877, while virtually no musician seems to go undocumented today. Somewhere between the droughts of yore and today’s floods, the 1960s saw relatively few recordings of experimental music released. This was in part because multimedia happenings do not transfer well to audio, but also because many innovators disliked recordings. This book takes its title from a quote from John Cage, who notoriously complained that fixed versions cannot adequately represent works that are inherently indeterminate. The few drops of music available contemporaneously have since been augmented by archival CDs and online resources containing digital oceans of previously unreleased material. What is the difference between ’60s music as experienced live versus that which remains on recordings, the availability of which has drastically increased over time?

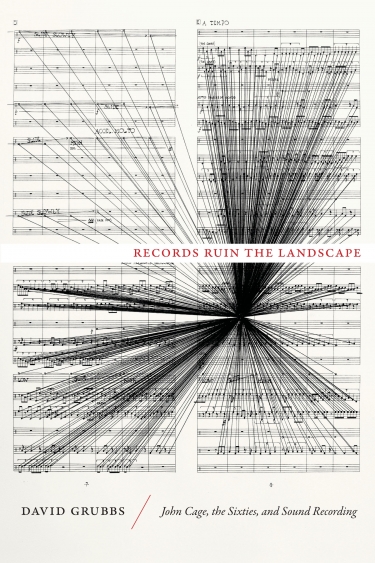

This question is given thorough treatment by David Grubbs, a professor at Brooklyn College and a musician who has played on over 150 releases, with Gastr del Sol, Pauline Oliveros, and many more. The monograph provides deep reflections for academics, including twenty-eight pages of references and notes, but is written in a conversational style that is sure to resonate for anyone interested in 1960s music.

The book interweaves narratives about ’60s experimenters with the history of recorded media. The opening chapter discusses Henry Flynt, whose unorthodox avant-hillbilly music went almost completely unreleased until the early 2000s. Chapters two and three turn to Cage, who loved to say he hated records, but paradoxically put out more of them than almost all his contemporaries did. Grubb’s comparison of Cage’s 4’33” and Luc Ferrari’s Presque Rien no. 1 is especially insightful, demonstrating the difference between a live performance (4’33” is different each time) and recordings (Presque Rien is repeatable). His reviews of Cage’s influence in music, dance, photography, and film are also well done.

Whether or not recordings contribute to improvised music is the subject of chapter four. In line with Cage, Derek Bailey felt free improvisation must be experienced live, but he ran a record label specializing in the genre. Jim O’Rourke, with whom Grubbs has often played, counters that there is so much information in any improv set that many listens, only possible through records, is essential. Chapter five brings the reader to the present day of Internet archiving. This allows a more complete, if still imperfect, picture of an era, but also brings copyright issues to the fore. Two divergent approaches to archiving are compared: DRAM that seeks permission, and UbuWeb that does not.

While my shelves will not yet be emptied of my antiques collection (as Bailey would call it), I will be listening with a broader understanding of the limitations of records heard out of time and context. Any book able to rock the foundations of modern armchair and mouse-click listening is surely worth a read.