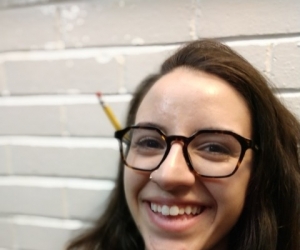

Vanese (pronounced va-NIECE) “VJ” Smith and I are on the Spadina streetcar, chatting like old friends. Just minutes earlier we met for the first time. I arrived from up North (aka Thornhill) in a state of winter-blues petulance, but when I saw her bright smile and waving arm from across the street, I was grateful that we’d finally connected.

On our way to her Leslieville apartment, where we’ll talk more in depth about her life and career, Smith seems to know someone everywhere we go. She waves at a man getting off the streetcar. She chuckles with a gentleman about “pancakes”—an inside joke that I don’t ask her to explain. At the little shop where we pick up food she converses warmly with the cashier. She is a social butterfly, able to connect with a diverse cross section of people wherever she goes. So I am not surprised when she says that in her creative life she works within many different worlds.

“I’m literally a part of three different scenes—and I love it: I’m part of an experimental electronic scene where I can play ambient, play weird, play soundtrack music. Then I’m part of this instrumental, hip-hop slash beats scene. I’m also part of that club-music life, which is that upbeat dance, house [music] 120, 130, 135, 140 shake-your-groove thing,” she says, making beat sounds as she counts out the numbers.

As a hip-hop producer, Smith has found success internationally, but she finds that the insular nature of Toronto’s music culture has meant a somewhat restricted view of her work locally. “When I do things, or if I get play or a write-up outside of North America, they’re a bit more [comprehensive in] describing what I do. I’m a music lover. I’m a sound artist. I have to express myself in all those ways,” she explains. “I’ve never been pigeonholed into what I was supposed to create. As a result I’ve always been hard to pin down when it comes to reviews. But as a creator-creative I wouldn't have it any other way. The thing that’s given me longevity is the fact that I’ve been open, genre-wise.”

Moving from scene to scene and finding her place in each is something Smith has always done. An only child, born in the Maryland suburbs of Washington, D.C., to a young, industrious mother, Smith was placed on the achievement track at a young age. In third grade she became a student at a “Fame-esque” performing arts school. There they studied everything: dance, theatre, media arts, music, and visual arts. The self-proclaimed goody two-shoes excelled (Straight-A student, National Arts Society secretary, Drama Club president), while effortlessly gliding between various social circles. She grew used to being “so many people in one,” in order to balance her diverse life. The only female rapper amongst her friends, she soon became the only woman producer as well. “I was the only female I knew making beats. And I’ve never stopped.”

At Vassar College—a private liberal-arts school with notable alumnae, such as Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Meryl Streep, and Anne Hathaway—Smith studied film, while immersing herself in Vassar’s excitingly diverse community of people. She became disillusioned with acting when she realized that her skin colour and gender were being used to typecast her. “I was used to an environment where it didn’t matter how you looked; you could play any character—in my senior year in high school I played a seventy-year-old German woman,” she explains. “But when I went to university it was more like, ‘No! This is what you look like. This is what you’re gonna play.’”

Smith quickly moved on, recognizing that “acting is acting” and that emceeing and producing her own work allowed her to be more. She became the campus DJ. She interned in New York City at recording studios and record labels. A childhood spent writing poetry segued into writing songs. She used the piano lessons she took briefly as a child, and taught herself the rest. Her habit of borrowing her mother’s old record player to play her collection of thrift-store twelve-inch LPs transformed into her doing her own “little rhymes” over twelve-inch instrumentals. Her rapper name became Pursuit, her tag line: “I seek, hunt, and capture ears.”

I ask if being a female emcee and producer in the late nineties and early 2000s came with harassment, and am pleasantly surprised when Smith says it did not. “I can only speak for me personally because there’ll be women who definitely say that they’ve experienced all sorts of negative things,” she says, her bubbly demeanour becoming thoughtful. “I’ve always been one of only a few females, but I’ve never felt out of place.” Taking on the androgynous name Pursuit, which eventually became Pursuit Grooves, was, she admits, strategic—vague enough to leave people wondering who was behind the music: is it a woman, a man, or a band? “I didn’t want to be Li’l Mama or Miss whatever,” she says, adding that instrumental and electronic music’s inherent ambiguity has always been freeing. “No one has to know what you look like. The music can speak for you.”

Though Smith was raised on her mother’s soul and R&B and her aunts’ rock and new wave, the first producers that caught Smith’s attention and admiration were Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, renowned for their work with Janet Jackson and numerous notable R&B artists. She realized then that producers could have their own sound. Teddy Riley, Timbaland, and Pharrell’s distinctive sounds further inspired her, yet they all belonged to that boy’s club of famous producers.

“I didn’t know any female producers back then. What I realized later was that there was Patrice Rushen; she pretty much orchestrates awards shows now—she’s a beast. Even someone like a Teena Marie: Rick James produced her stuff, but she played the guitar, she wrote lyrics. She was a beast. It wasn’t until later that I got into the history of it.”

Smith now makes a concerted effort to ensure that the next generation of female producers know their “her-story.” A few years ago, she started teaching female-only workshops at the Off Centre DJ School in Toronto. Her goal, she says, was “[to foster] a safe space, build community, and take away the intimidation factor behind production.” More recently, as a mentor in the EQ: Women in Electronic Music program—developed and directed by electronic composer Rose Bolton and presented by the Canadian Music Centre—she is offering the mentorship experience she never had. “It’s a very unique program for young women, [based] around production,” she says, a few weeks before kicking off a training session. “We have a lovely group who have already done so much in their craft but want to learn other techniques in their work. I lead a session on creative ways to use samples and found sound—whether it be a door slamming or a chainsaw. These sounds are candy for me!” Her brand new release, Felt Armour, will be used as an example of making ear candy out of sounds not normally associated with music.

Her first album, Fun like Passion, self-released in 2006, was mostly hip-hop instrumentals, representing the beat world. “I played every note and created all of the drum patterns from scratch.” Because she could not redo errors made in the recording process, Smith became a perfectionist, making sure everything was right so that she could get that “one take.” She looks back now and sees how it made her a better producer.

“I don’t think I could do that again. It was really in the moment. Like, little wizards came through. I layered on top of each other so I couldn’t go back. There’s certain things on that album where I don’t know how I did it. I played everything. I composed everything. There are no loops in that album. I really had to perfect my mixing skills.” That diligence paid off. Fun Like Passion put Pursuit Grooves on the music map. “That project led to everything else. That was the album that got me my first track, “Push Up,” on vinyl, a compilation [Beat Dimensions Vol. 1, Rush Hour Recordings, 2006]. That was the album that got me my first bit of attention, write-ups in music magazines. It was a big deal.”

Since, she has made six full-length recordings and four EPs, each drawing on a different passion (e.g., poetry, unusual nonmusical sounds), and on personal events, even her grandfather’s death. And just like the producers Smith admired, she’s become known for her own sound, something fans can sense and submerge themselves in, despite how eclectic her work is. “Drum programming is my thing. A mixture of different rhythms that I’m not afraid to explore. And I love bassline. I’ll put a bassline on anything,” she says, excitement revealing a trace of an American accent. “Then hard bottoms, full of bass, percussive, aggressive, and intricacy. And then soft, silky, sensual tops,” she concludes, with a mischievous smile.

While gear is an integral part of her music, Smith, both as artist and mentor, steers clear of taking on a technical “nerdy perspective” and obscuring the creative process. “I know tons of people with lots of gear who aren't very creative, and folks who have little and do wonders,” she explains. “I'm almost more creative when I have limited options or I challenge myself to use what I have in new ways.”

Smith’s creative tools have morphed over the years. As a teenager she used birthdays, holidays, and allowances to build up her bedroom studio. “Back then I had a Yamaha PSR 410 synth with multitrack abilities, a Fostex cassette four-track, Roland TR505 and Roland MS1 sampler—all by eighteen years old.” Over time, she got hooked on the Boss SP505 sampler. “I have three now, and it’s a piece of gear I’ve been known for using in studio as well as live.” She recently started dabbling in software synths, while the Juno106, Nord Lead synth, Waldorf Blofeld, and the Microkorg synth help round out her tools of the trade. “I like to exhaust as much of my gear [as possible] before hopping to new things,” she says.

Yet, she insists, the one invaluable tool is what’s happening in the world around her. “I really enjoy incorporating found sound into my production work."

As the day winds down, we sit in her combination home studio and living room, listening to her music. I look around and see a painting by Toronto artist Adrian Hayles hanging alongside works of her own visual art. In 2015, Smith took time off from music to work for a year and a half on this other major area of her creative life. “I’m just happy that I know myself well enough to know that when I need a break, I take a break, so I never lose the love for [music]. I don’t ever want to lose the love for it.” That time off allowed for the evolution of Mo:delic Arts, her growing line of graphic designs that she’s produced as art prints and as adornments on fashion pieces and home furnishings—everything from shirts to shower curtains. “Visual art for me is literally the equivalent of music. It’s the same,” she explains. “[My music] has tribal elements, tribal drums. It has colourful elements, sometimes dark, sometimes bright. It has things that make you revisit it. And you might not immediately get it, but dig deeper.”

Smith is now preparing to release her seventh full-length album. She tells me that the new ways people are producing and releasing their music has reinvigorated her passion for making it. And in many ways, all the things her music is—genre traversing, ambiguous, impossible to categorize—is exactly what the industry and audiences are looking for today.

“My life is a whole sequence of events that leads from one thing to another to another. And I don’t feel like, ‘Oh, I’ve been doing this for so long. I’m so old school.’ No! I never fit in to begin with, so I’m always right on time—because I’m on my own time.”