Tona Walt Ohama has lived many lives. Born on a potato farm in Southern Alberta, he has spent the past forty years making passionate, deeply personal music while forging friendly connections with anyone who enters his orbit. Since his debut album, the 1982 cassette release Midnite News, Ohama has become a prolific producer and sound-art composer, as well as a community advocate for Calgary’s most marginalized people.

Throughout his first decade as an artist, Ohama’s independently released albums achieved a modicum of mainstream success, thanks to award nominations, radio airplay, and videos aired on Canada’s MuchMusic channel. Those accolades mean nothing to him anymore, he tells me during a video call from his home in Calgary.

“It doesn’t matter who you are or where you’re from,” says Ohama, who is now in his early sixties. “If you make an interesting recording, someone is going to hear it and tell someone else, and that’s how it spreads. You can never, ever, get success on purpose.”

Ohama grew up on two thousand acres of farmland near the humble hamlet of Rainier, Alberta. His father, Tona Ohama, known as “The Potato King,” sold spuds and Tona Goldentop potato chips to stores across North America. Peak-season production often required fifty employees, many of whom would live with their families on the farm. Ohama recalled the parties that took place each payday. “Sometimes my job was to go over and get people to come to work the day after,” he told Calgary journalist David Veitch in 2018 (The YYScene). “I dreaded that. I was just a kid.”

In these formative years, Ohama began listening to records with his three teenage sisters. By age four, he was a full-blown Beatlemaniac; by age ten, he had discovered progressive rock and keyboardists like Tony Banks (Genesis), Rick Wakeman (Yes), and Keith Emerson (Emerson, Lake & Palmer). Ohama never expected to see firsthand a synth like the ones they played. Then, one day during a trip to Edmonton for a judo tournament, he walked into a keyboard store and was shocked to find an ARP Axxe for sale.

“It was turned on, so I touched it,” Ohama remembers. “When I heard the sound, I said, ‘I want that!’ At that time, when I was fifteen, we didn’t even have calculators in school or personal computers. This looked like the control panel of an airplane. It was way beyond anything.”

Ohama spent his life savings of one thousand dollars (a hefty amount in 1975) and took the synth to friends’ houses in Rainier. “I didn’t play music; I played sounds,” he says. “Imagine a bunch of teenagers in the country smoking weed and playing with this machine in the days before video games.” By the time he began engineering studies at the University of Calgary, Ohama’s instrumental skills were advanced enough for him to join the cover band Merlin, playing prog-rock songs—but only commercial hits like Yes’s “Roundabout.” While building pyrotechnics and wearing top hats on stage was fun, it wasn’t his ultimate fantasy.

“There was nothing magic about it,” laughs Ohama. “I had dreamed of playing with a bigger band, but being an Asian Canadian I knew there was no way I was going to be a frontman. I never wanted that anyway, because I’m not that kind of person.”

After university, Ohama produced a five-year plan to write original songs, hit the road, and pursue music full-time, but his father asked him to return to help on the farm, and so he hit pause on his musical life. When Bruce Toll, his former Merlin bandmate, brought over a copy of John Foxx’s solo electronic album, Metamatic, Ohama saw new possibilities. “That album switched a light on in my head. People like Tomita or Wendy Carlos were doing solo records, but I had never heard anyone sing with a synth before John Foxx. I thought, I could do that, and started working towards it.”

Ohama’s astonishing music from the 1980s was recorded in the basement of his family farmhouse, using synths, drum machines, and an Otari eight-track tape recorder. He immediately ventured into uncharted territories, fusing autobiography with escapism; his lyrics range from everyday life on the potato farm to Cronenbergian body horror about a friend who watched so much TV that she became one. Songs stretch beyond eight minutes, as field samples, sputtering grooves, and pitch-shifted vocals collide with Ohama’s impassioned New Romantic delivery. His 1982 song “Mushin No Shin” (a Zen expression meaning “the mind without mind”), with its discordant, improvised piano solo drizzled with electronic effects, is an early example of his experimental tendencies.

With the release of his 1984 debut LP, I Fear What I Might Hear, Ohama began to receive attention far outside his home town. The singles “Of Whales” and “Where Do You Call Home?” captured the ears of influential CFNY radio hosts Liz Janik and Peter Goodwin, while a low-budget video for “My Time” (featuring Ohama being executed by electric chair) found its way onto MuchMusic. In 1985, he travelled to Toronto for a rare live performance, receiving coverage from CBC’s Brave New Waves program and an interview on the nationally syndicated TV program The NewMusic, during which he was asked if working in his basement studio in the prairies felt like a post-apocalyptic vision. “I think you get a lot of personal power growing up in a place like that,” he answered. “Being isolated, I’m not affected by a lot of things. It’s bad on the one hand, because you don’t get all the influences, but you can focus a lot better. I don’t get caught up in trends.”

Ohama received a nomination in the Best Independent Artist category of the 1985 CASBY (Canadian Artists Selected by You) Awards, and attended the televised ceremony, which featured homegrown celebrities such as Paul Shaffer, Carole Pope, and Gowan. “After the ceremony, I quit music because I didn’t want to have anything to do with it,” he says. “That was my first televised awards show, and I didn’t like the fakeness or how competitive it was. People cooperated where I came from, but Toronto felt really cutthroat. I wasn’t interested in winning that game, and I’m still not.”

The ’90s were a relatively quiet period for Ohama’s music, but not his personal life. He touches on these struggles—such as the custody battles following the birth of his son—in the lyrics of his expansive, emotionally charged comeback album, On the Edge of the Dream. In 1994, Ohama booked the Calgary Planetarium for a ten-night residency, but these ambitious multimedia sets were woefully under-attended. “One show, we had three people,” he told Veitch (The YYScene). “It holds 350 people. Those shows were just heartbreaking, honestly.” Feeling defeated by the disappointing audience turnout and by negative reviews of his album, Ohama accepted a job offer from his old friend Doug Wong at Canada Disc and Tape, which had manufactured several of his previous releases. In addition to assembling music projects in every imaginable genre and format, Ohama worked on industrial training DVDs for airlines, banks, and local schools.

“By the end of a shift, when you’ve been working with music all day, you don’t want to think about it,” he recalls. “So, I quit again. I wasn’t writing any music or recording at all. The ’90s were all about helping other people get their projects out.”

Stricken by suicidal thoughts after once again losing custody of his son, Ohama found himself perilously close to living on the street as a result of his financial situation. The low-income building in downtown Calgary that he called home had become overrun with drug users. To counter this downturn, Ohama began sweeping the streets around the building for hours each day, inspired by something he read in Malcolm Gladwell’s The Tipping Point.

“[It says] that if a window is broken, another one will get broken soon, and everything will deteriorate—but if you fix the window, you can repair a neighbourhood,” Ohama explains. “I really believed that, so I started sweeping and picking up cigarette butts. Through that process, I met everybody out there: business people, police officers, transit cops, addicts, and dealers. I became untouchable. Nobody would mess with me because I was helping the street.”

For the first three months of his 7th Avenue SW recovery project, Ohama emailed his sister every day with stories of his progress and the people he met. She forwarded the messages to friends in New York and Los Angeles, and Ohama’s street sweeping became a widespread source of inspiration. He credits those ninety days of ground-level connection with saving his life, and has kept the emails in a scrapbook that he hopes to publish one day.

Street sweeping led to Ohama’s chance meeting with the young folk singer Solstice, whose songs were “real and genuine” and reminded him of why he turned to music in the first place. Producing Solstice’s 2008 debut album, This Moment Will Never Happen Again, reignited his interest in his own music, and he went on to release a career-spanning ten-disc box set. Around the same time, Ohama met Veronica Vasicka, founder of New York’s Minimal Wave Records, which released The Potato Farm Tapes compilation and introduced his music to a new generation of listeners.

“At first, Ohama was feeling very lonely and felt the need to express himself,” Vasicka said in a 2012 interview with Dazed. “In many cases these artists felt some sort of isolation and wanted to reach out and touch other artists. I don’t think it was a direct response to what was happening in pop music, it just had to do with the newfound respectability of using synthesizers. The majority of the artists weren’t expressing frustration, they were just expressing themselves and the period. It was purely an artistic mission.”

The 2010s yielded a bumper crop of new music from Ohama, in addition to a series of momentous life events that included marrying his present wife, Mia, and heading up north to work as a dishwasher in the Alberta oil sands. Earth History Multiambient (2010) was his first album of new music since 1994. Combining humorous songs with deadly serious lyrics, the collection culminates with Earth, a sixteen-minute eco-rap epic unlike anything else in his dense discography.

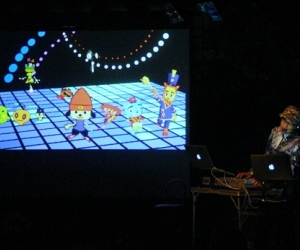

In 2012, Ohama released Thick As A Brick: The Synth Edition, a faithful note-for-note recreation of Jethro Tull’s 1972 album. This was followed by his instrumental soundtrack for the film Pull and by the first in a series of site-specific installations transmitting his music throughout the city’s downtown core. The 2017 collection Grrlz Monosynth Tower includes an album of Ohama’s “multiambient soundscapes” beaming out from the Calgary Tower, plus his collaborations with nine female vocalists (including Solstice). My Electronic Country Album (2021) was another massive undertaking. Autobiographical spoken-word passages are woven through its twenty-nine songs—bleepy covers of prairie wedding-reception staples such as “Wichita Lineman,” “Forever And Ever Amen,” and “Kiss An Angel Good Morning.” He had been listening to eight-bit covers of Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin, and wanted to make a similar album. “For my previous album, no one had seen the liner notes, so I thought I would record them this time,” he explains. “That sounded like crap, but it evolved organically into stories about each song. Nothing was planned.”

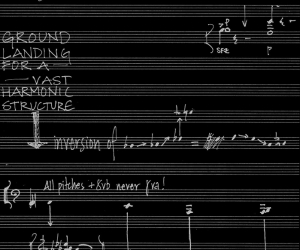

Now in his early sixties, Ohama continues to conjure electronic sounds in his head as the capabilities of technology finally catch up with his otherworldly imagination. His next release, set for 2023, is Dorothy Bishop Cello Soundcapes, a multispeaker installation featuring manipulated recordings of improvisations from the acclaimed Calgary cellist. Gazing even further afield, Ohama will release a collection of new renditions from across his own catalogue. Trimming them down to radio-friendly lengths, he can finally hear the pop songs he’d composed in his head as if they were hits in an alternate dimension.

“It’s the best album I’ve ever made,” says Ohama. “I’ve never been happier with how the synths and vocals are sounding. Back when I was recording those songs originally, I didn’t have the technology or the ability to do certain things that I wanted to do. Now, it seems like everything I’ve done until this point was preparation for this moment. It’s all coming together.”

FYI: In January 2023, Ohama will release a recently uncovered recording of his June 23, 1985, performance at Edmonton's Chinook Theatre. The digital album will be available on all streaming platforms.

PHOTOS: By Allison Seto.

Listen to Ohama on Bandcamp.