“God is alive / Magic is afoot / Alive is afoot / Magic never died.”

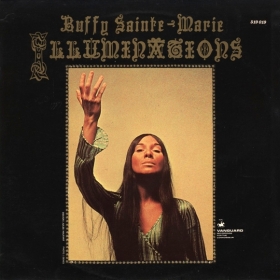

Those words, written by Leonard Cohen and sung by Buffy Sainte-Marie, open a doorway into the mystical world of Illuminations—one of the most musically beguiling, technologically groundbreaking, and undeniably brilliant albums of the 1960s folk era. Unlike a few of Sainte-Marie’s earlier albums, Illuminations failed to find commercial success upon its release in 1969, and fifty years later, it has yet to receive widespread appreciation. Though many musicians, listeners, and critics consider it their favourite album in Sainte-Marie’s sprawling discography, the stories behind its innovative combination of acoustic and electronic sounds have remained largely untold over the years.

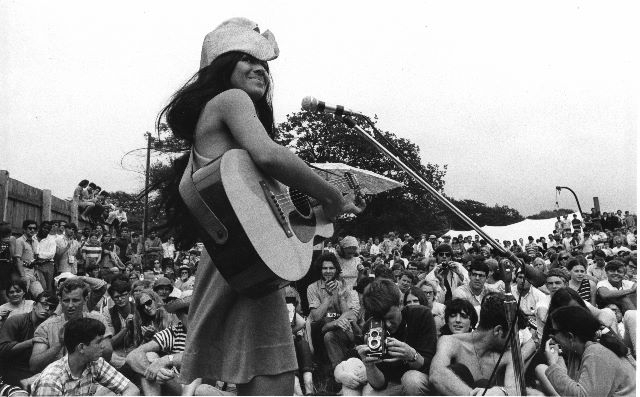

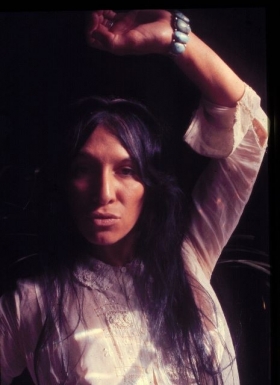

By the end of the 1960s, Sainte-Marie’s music was well known, even if she was yet to become a household name. Donovan landed on the charts with his cover of her military protest song “Universal Soldier”; Janis Joplin created shockwaves with her riveting take on Sainte-Marie’s drug-addiction meditation “Co’dine”; Elvis Presley, Françoise Hardy, and the Monkees were among many notable artists who covered “Until It’s Time for You to Go.” Fans and critics were taking notice as well, with Billboard naming Sainte-Marie the best new artist of 1964 and crowning her “the new patron saint of the non-hippie hipsters.”

Born in the Piapot Cree First Nation reserve in Qu’Appelle Valley, Saskatchewan, Sainte-Marie took the title of her debut album It’s My Way! (1964) as her mantra as she became more widely known. Sainte-Marie never caved to the pressures of the industry nor did she desire to play the game. She preferred to help others, including carrying around a cassette of Joni Mitchell’s demos, which she played for every record executive who would listen, until Mitchell got her break. While Sainte-Marie’s folk peers fought for civil rights in big-city marches, she focused on bringing awareness to Indigenous issues, for example, taking African-American civil-rights activist and comedian Dick Gregory on his first visit to a reservation so he could spread the word about less-documented injustices.

Sainte-Marie was no stranger to sonic experimentation. The rock band on her 1967 album Fire & Fleet & Candlelight was augmented with electronic orchestral arrangements. She galloped in the opposite direction on I’m Gonna Be A Country Girl Again (1968), travelling to Nashville to record with Chet Atkins. For Illuminations, her sixth release, the twenty-eight-year-old artist moved even deeper into left field. With her blazing band and hair-raising vibrato at the peak of its powers, Sainte-Marie wove together songs through spectral Buchla-synth samples of her voice and guitar, fearlessly fusing genres while exploring the natural, spiritual, and metaphysical worlds.

“My philosophy was to bring something that nobody else was bringing,” Sainte-Marie says during our summer 2019 interview. “No sense in trying to be a second-rate Joan Baez or Judy Collins. I’ve always liked covering the bases that nobody else was covering. Since I was so early with electronic music, and so few others in the industry appreciated it, I learned to use it as a spice, not as a meal.”

Throughout the presidential terms of Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon, empowered by the iron fist of FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, many radio stations across the U.S. blacklisted Buffy Sainte-Marie’s music because of her outspoken antiwar lyrics. “Here’s how it was done,” she explains. “A couple of guys in the administration go into the back room and make calls to their cronies at the networks, and airplay stops.” While she didn’t learn about the ban until years later, the cycle of recording and touring, spurred on by her label Vanguard Records, had by itself started to take an emotional toll.

In the late 1960s, to avoid burnout, Sainte-Marie left bustling Greenwich Village for the tranquil greenery of Hawaii. While this visit was intended to be short term, she ended up meeting someone, got married, and has lived in Hawaii ever since. Through a mutual friend of that husband (she later remarried), Sainte-Marie met guitarist Robert Bozina, who was studying philosophy at Santa Clara University. While rehearsing and recording together, they cowrote the rollicking song “Native North American Child” before touring across the U.S. and Italy.

In early 1969, Sainte-Marie returned to New York to record Illuminations. Bozina invited to the studio the drummer John Craviotto, who had previously lent his steady stickwork to Otis Redding, Ry Cooder, and Moby Grape. The band was rounded out by bassist Eric Oxendine, a Lumbee Native American who was discovered by Richie Havens’ producer and photographer Mark Roth while performing at Greenwich Village hotspot Café Au Go Go. Oxendine’s claim to fame includes playing with Jimi Hendrix, Muddy Waters, and Van Morrison, as documented in his book Jammin’ With Jimi.

Though Sainte-Marie’s new quartet performed only three of the twelve songs on Illuminations, the musicians’ contributions to the album’s hard-hitting sound are paramount. Less than two minutes into “With You, Honey,” the quartet lays down a stomping rhythm and squealing riffs while Sainte-Marie unleashes furious wails akin to Yoko Ono’s vocals in “Approximately Infinite Universe.” “Guess Who I Saw in Paris” is the languid calm in the eye of the storm, setting the stage for the album’s most raucous cut, and one of Sainte-Marie’s finest musical moments, “He’s a Keeper of The Fire.” Fans of that song include Oasis’ Noel Gallagher, who selected it for his MOJO Magazine compilation, Well… All Right! A 15-Track Musical Journey: on a track list that includes Black Mountain’s rendition of “No Satisfaction” and Nina Simone’s live version of “House of the Rising Sun,” Sainte-Marie fits right in. Propelled by a filthy, swaggering groove, “He’s a Keeper of the Fire” pays tribute to the bad boy in Sainte-Marie’s life, and she belts it out: “He’s got a funny kinda voodoo, baby / You oughta see him at the zoo / He’s got a heavy kinda hoodoo, baby / And he can lay it on you.”

“When we were doing ‘Keeper of the Fire’ it got a little hot, as she liked it,” remembers Oxendine during a recent exchange. “We got a bit more blood pumping into the arrangement, which was exciting. [The album] was all scattered, so I said, ‘You need some rock and roll in there.’ That’s how I wrote the bass line.”

While Illuminations’ sundry song styles may preclude slotting the album into a tidy classification, Sainte-Marie is quick to point out that this has been her modus operandi from the beginning. It’s My Way! included a song written in Hindi (“Mayoo Sto Hoon”), oddball tuning (“The Incest Song”), and an Appalachian folk standard played on a mouthbow, which uses harmonic overtones from inside the player’s head (“Cripple Creek”).

She defies expectations even more fiercely on Illuminations, quivering over gothic organ sounds on “Mary” and trilling like her hero Édith Piaf to the sound of swelling strings on “The Angel.” A slow-burning freakbeat cover of Richie Havens’ “Adam” links up thematically with those biblical allusions, while the dark banjo hoedown “Better to Find Out for Yourself” is a cautionary tale about deceitful men who’ll “love you some” then “laugh and let you go.” Sainte-Marie sounds even bleaker on “Suffer the Little Children,” a Pink Floyd–style condemnation of unfit mothers pushing their babies into the capitalist nightmare of devils dressed in suits. “Did you think he’d be a bogeyman?” she shouts, warning listeners against a hell-on-earth of our creation.

“I had a concept in mind for the album, both deep and shallow, and I stick up for both,” says Sainte-Marie, who studied world religions while at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. (She graduated in 1961 with a double major in teaching and Eastern religion.) “At the time, I was loving illuminated manuscripts—like the ones in museums that portrayed the lives of saints. If you look at these beautiful works of art, you see a diverse world of angels, demons, miracles, cruelty, martyrdoms, wonders, and glorifications of all kinds. By being all over the place, it has its own gestalt, like the whole world taken together.”

Another unlikely contributor to Illuminations was composer, educator, and music satirist Peter Schickele, best known for his beloved comedic character P. D. Q. Bach. As an in-house arranger for Vanguard, he provided orchestral backdrops for “Mary,” “Adam,” and “The Angel,” just as he had on her previous album, Fire & Fleet & Candlelight. However, after Sainte-Marie heard initial mixes of Illuminations, she requested a “spacier” sound, resulting in the electronic postproduction that would transport the album into truly groundbreaking territory.

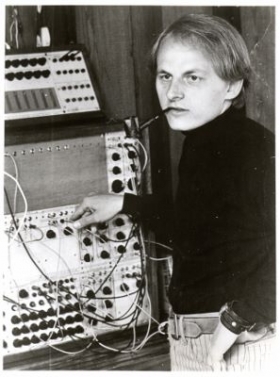

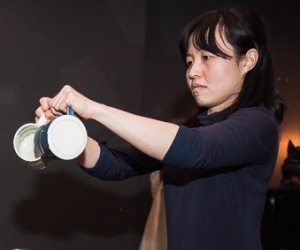

Schickele moonlighted as a music teacher at New York’s Juilliard School, where he worked alongside Michael Czajkowski (pronounced “Tchaikovsky”). At this time, Czajkowski [see photo below] had come in possession of the Buchla Model 100 synthesizer, a pair of wooden cabinets filled with retro-futuristic racks of dials, wires, and peg holes that Sainte-Marie says “looked like what a Lily Tomlin telephone operator would use in 1950.”

When Czajkowski first heard Sainte-Marie, he was smitten: “Back then, she just strummed her guitar and you would swear that the room changed colour. I don’t know if you would call that musicality or mysticism.”

Morton Subotnick was the previous owner of the Buchla Model 100, which he used to record his influential late ’60s album trilogy of Silver Apples of the Moon, The Wild Bull, and Touch. After moving across the country from his job at Mills College in Oakland, Subotnick set up his synths at a Bleecker Street loft and launched the NYU Composers Workshop. It was here that he came in contact with Czajkowski, who would go on to perform alongside or to teach future electronic titans such as Alvin Lucier, Nam June Paik, and Laurie Spiegel. The Model 100 was also used to create Czajkowski’s only solo album, People the Sky. That album’s gale storm of modular gurgles provides an excellent counterpart to Silver Apples of the Moon, and was issued by Vanguard Records the same year as Illuminations.

The dawning possibilities of electronic music had captured the minds of the mainstream at this time, thanks to the BBC Radiophonic Workshop’s Dr. Who theme, Gershon Kingsley’s novelty hit “Popcorn,” and Wendy Carlos’ Moog masterpiece, Switched-On Bach. However, no one had attempted to connect the seemingly opposing worlds of folk and electronics until Sainte-Marie swooped in with her radical concept.

With the magical touch of Czajkowski, Sainte-Marie’s voice and guitar were manipulated through the Buchla’s watery, wraithlike effects. Czajkowski’s Juilliard colleague Luciano Berio’s 1961 piece “Visage,” which transformed the wordless utterances of his wife Cathy Berberian into something truly terrifying, was a primary influence. The songs of Illuminations were then further enhanced with an array of robotic sputters, trippy tape loops, and hazy chemtrails, melding its songs into continuous sidelong shimmers. Unobtrusive but completely otherworldly, Sainte-Marie’s sonic spirits crossfade from side to side like ghosts haunting the headphones or speakers in quadraphonic sound.

“I didn’t want to just plop electronic sounds on top of what Buffy had done, because that wouldn’t have been very organic,” recalls Czajkowski from his home in Aspen. “The label gave me a copy of the album, and I manipulated that with the Buchla’s filtering, modulating, and gating effects. I thought about the cover photo, the Leonard Cohen poem, and how it was about mystical stuff. That set the tone in my mind for what she was doing. I wasn’t going to add any groovy beats or anything, because those were there already. It was more like a sonic veil, because I wanted to enhance her songs instead of overpower them. They gave me her original recordings and I just sat there and dreamed.

“I created stereo tracks for each of the songs and of course it was edited way down, mainly to intros and transitions,” Czajkowski continues (which sends one’s mind racing to imagine an entire album-length version of his electronic manipulations). “My tracks were laid down separately from what she had done in the studio, and then the engineers went through it. They used what they liked of it and that was that. I hadn’t met Buffy at all before the album was recorded, but she was really happy with what I had done. She was even interested in working on another album together, but it sadly never made it to the concept stage.”

Illuminations’ mind-expanding experience is bookended by its most imaginative songs. Sainte-Marie’s feverish reading of “God Is Alive, Magic Is Afoot,” a poem from Leonard Cohen’s 1966 novel Beautiful Losers, was completed in a single take. She describes her process in a section of her Web site: “I propped two pages of his book on a music stand and I just sang it out, ad libbing the melody and guitar music together as I went along. I love the way the power of the words obviously commands the music and drives it beyond any consideration of time signature.” Czajkowski’s treatment of “God Is Alive” makes the song mesmerizing, but his pièce de résistance comes on the album’s closing cut, “Poppies.” Accompanied by a sparse acoustic guitar, Sainte-Marie’s voice becomes one with the synthesizer in a crystalline cave of electronic echoes. Predating the sound of Animal Collective’s collaboration with folk singer Vashti Bunyan by nearly forty years, the song has also been acknowledged by Genesis guitarist Steve Hackett as a formative influence. As Illuminations comes to a close, the opening words from “God Is Alive” return like a lysergic leitmotif before swirling back into the afterlife forever.

The opening lines of “Poppies,” which are among Sainte-Marie’s most poetic, are intoned with a gentle waver: “I tippy-toe across your dream each night / So as not to wake you.” On the LP’s back cover, the song includes a dedication to Mr. Allerton, whose identity has been a mystery for the past five decades. Over the phone from her home in 2019, she solves it with a gleeful laugh.

“When I first moved to Hawaii, John Gregg Allerton had a huge piece of property that had formerly been owned by one of the royal families. It was absolutely beautiful and was later turned into the Pacific Tropical Botanical Garden. A bunch of us hippie musicians used to sneak in there. It wasn’t a garden for the public just yet, but there were a lot of beautiful little paths and hobbit caves where we would hang out. One time we got caught, so I got to meet Mr. Allerton. He threw us out but he was really nice. I ended up devoting the song to him as a kind of apology.”

Fifty years after its release, Illuminations would not now be out of place as the illustration for a reference-book definition of the term “cult favourite.” Despite failing to crack the Billboard Top 200, the record has earned a handful of glowing retrospective reviews from Allmusic, Julian Cope’s Head Heritage, and The Wire, which included the album in its 1998 feature ‘100 Albums That Set The World On Fire While No One Was Listening.” There, British journalist Biba Kopf penned a hilarious piece of alternate history. “If Dylan going electric in 1965 turned folk purists into baying hyenas, Buffy Sainte-Marie going electronic would have turned them into kill-hungry wolves, if they weren’t already a spent force.”

Andrea Warner, author of Buffy Sainte-Marie: The Authorized Biography, finds it equally frustrating that the album has yet to be recognized as revolutionary. While Sainte-Marie has continued to innovate throughout her career—sampling powwows on her 1992 album Coincidences and Likely Stories, creating an online Indigenous education resource with the Cradleboard Teaching Project, and becoming the first woman to breastfeed her child on Sesame Street—her generally accepted contributions to musical and cultural history largely remain limited to her songs. Warner believes this is due to a toxic mix of racism and sexism that continues to poison the patriarchal media well.

“I think a lot about the idea of someone knowing in their heart that they’re doing something innovative, experimental—and at least five to ten years ahead of their peers—and for that thing to go unnoticed,” she says. “I know Buffy doesn’t need external validation, and that’s not [why] she creates music or art, but she is part of an industry, unfortunately. People need to at least acknowledge your contributions and not just ignore them, [which is] erasure. We know the reasons why you can’t find a bunch of stuff written about this record. It’s such a shame, an invalidation, and an indictment of music journalism.”

But Illuminations does have its fair share of fans among electronic artists of note. These include U.K. producer Bullion, who turned “God Is Alive, Magic Is Afoot” into an elastic disco track on “Magic Is Ruler” (2011). Vito Roccoforte, drummer of the Rapture, used “Poppies” as the basis of a bumping edit, while Anticon rap crew Deep Puddle Dynamics spit fire over Sainte-Marie’s vocals on 1999’s “Purpose.” Most recently, multinational hip-hop collective Humble Drum Circle sampled “Poppies” on their claustrophobic posse cut “Paths of Ice.”

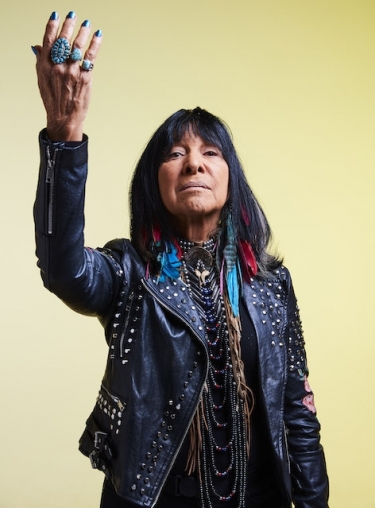

For many Indigenous musicians working in electronic and experimental fields, Sainte-Marie is far more than just an artist to sample. Navigating a five-decade career on her own terms while continuing to release acclaimed albums such as the 2015 Polaris Prize winner, Power in the Blood, and remaining an enchanting live performer at age seventy-eight, she has continued to prove that any barriers can be overcome.

“Her being is a giant influence,” says

cellist and electronic musician Cris Derksen, who performed on

Power in the Blood. “She has such strong convictions, following her heart so dearly and intensely. It’s so powerful to see someone do that, because it gives you the feeling that you can too. Buffy opened the door for all Indigenous artists making a career out of being a great musician. She has earned great respect, and doesn’t just the talk the talk but lives it. She’s the great aunty for all of us.”

“What’s inspiring to me is the way Buffy has always led her life,” echoes

noise artist and composer Raven Chacon. “She’s made the music she wanted to make and did not play the game in the way some folksingers decided was the proper way to do it. She’s held her stances and convictions throughout her career, and

Illuminations is sonic evidence of that. Confusing the music and having other presences beyond her voice would have been the last thing her contemporaries wanted to do. To me, that kind of experimentation and vision is what defines her as an innovative artist.”

A Tribe Called Red’s Ehren “Bear Witness” Thomas and Tim “2oolman” Hill are also among Sainte-Marie’s admirers. The duo’s remix of her 2008 song “Working For The Government” has become a staple of their live sets, with Sainte-Marie’s voice riding the groove of speaker-rattling beats. Their upcoming album is a collaboration with pioneering producer Malcolm Cecil using his legendary TONTO synthesizer, which was developed in the same years as the Buchla Model 100 and now lives on at Calgary’s National Music Centre; A Tribe Called Red’s use of it preserves and furthers the Indigenous electronic continuum.

“Listening to Illuminations now, I hear all of those wicked tape-delay effects where they just ride it,” says Bear Witness. “Tim and I were literally playing with that same technology a few months ago with this big modular synth. I wouldn’t know what that was if it wasn’t for Malcolm Cecil showing us. We learned how to create a never-ending sound without any distortion. There’s this whole connection with our work right now that feels very full circle.”

“I don’t think Illuminations could be any more perfect,” adds 2oolman. “It’s flawlessly executed, right down to the way they melded Sainte-Marie’s vocals with the synth. I don’t know if it was intentional, but it seems like they were trying to create an organic electronic sound. It wasn’t overbearing. Back then, electronics were used as a main instrument, almost like a vocal; but they kept her at the forefront of it all. Her voice influences the synthesizer. It’s the perfect marriage of both electronics and Sainte-Marie. That’s definitely an inspiration for our projects to come.”

All 2019 photos of Buffy Sainte-Marie by Genevieve Caron. Archival photos of couretesy of Sainte-Marie, except the photo of Micahel Czajkowski, which courtesy of Czajkowski.

Audio: "Poppies" (1969) by Buffy Sainte-Marie, from the album Illuminations (Vanguard Records, 1969).