If there is a through line connecting traditional Eastern European klezmer, indie rock, and experimental drone music, it can be found in the work of Jessica Moss. Whether her music is acoustic or electronic, post-rock or post-classical, a stark and dramatic amplified violin performance or a lively klezmer tune with mandolin and Yiddish vocals, Moss’s sonic signature is both eerily recognizable and utterly timeless.

Moss grew up in Toronto and Montreal studying classical piano and violin, and has played with a range of different artists—including Carla Bozulich, Vic Chesnutt, and Feist. She spent fifteen years as a violinist in the Montreal post-rock group The Silver Mt. Zion Memorial Orchestra and five years with the nouveau-klezmer quartet Black Ox Orkestar before going solo in 2014. Since then, she has created four devastatingly beautiful recordings of processed violin music, with occasional vocals and other instruments added sparingly. She will release a fifth album, Galaxy Heart, in October on Constellation Records. It marks another shift in a career that has been full of them.

“Performing solo after twenty-plus years of only being in bands was a really big transition, and it came pretty late in my life,” she says. “I was already an adult for twenty years when I started, and I didn’t think I was going to do it, so it sort of surprised me. It felt like a gift in a way, but it also put me through some painful paces of learning how to be that isolated and also engage with the world and allow myself to go as far into my head as I have tendencies to do and not let it make me into some crazy Beethoven person.”

Like most musicians, Moss was unable to perform live for a good part of the COVID-19 pandemic—there was a 10 p.m. curfew in Montreal for a time—but she found a silver lining in the forced solitude, as it enabled her to take the time to write and record two albums: Phosphenes (2021) and Galaxy Heart. In a way, the pandemic was a blessing in disguise for Moss, allowing her to achieve the kind of intensely focused concentration she needs to create her music.

“The pandemic, the isolation, the curfew: all meant that for the first time in my life I had actual time to work on something without the constraints I’m usually working under,” she says. “Once I launch into making a record, I’m pretty much completely occupied by it, to the point of not being aware of anything else, so I have to plan for it. I’ve learned from my mistakes of not planning for it and becoming encircled and feeling that I was going to melt into pieces. This time was different. This time I had no idea if anyone would ever play a music show again or put out a record or ever see anybody again, while at the same time being in this supremely ridiculous privileged position of being Canadian and receiving a regular CERB paycheque. It was so weird, the feeling of not having this constant hustle.”

Unencumbered by the demands of pre-pandemic life, Moss went into Hotel2Tango—the studio space shared by members of Silver Mt. Zion and Godspeed You! Black Emperor—and started playing. “I took a week and a half in there by myself and just played and recorded as much as I wanted,” she recalls. “And I spent the next entire year crafting them. There’s no differentiation between the music on Phosphenes and the music on Galaxy Heart; in fact, they’re not even all of what I made in that time. I gave myself no constraints. I just allowed it all to come. And I almost lost my mind trying to finish it, because that’s what happens when I have no constraints: I don’t understand how to stop or when to stop or how to engage—even how to make dinner—when I’m in the middle of it.”

Moss’s way of composing and making recordings is unusual, in that she doesn’t write her music down. In fact, ever since her childhood studying classical piano and violin, she has felt limited by a learning disability that prevented her from reading music or understanding music theory, which she hid by memorizing whatever she heard and replicating it—even when she played in the Toronto Symphony Youth Orchestra. It’s a talent—maybe even a kind of genius—that she’s always thought of as a flaw.

“I didn’t ever want to give up playing in orchestras, because I loved it so much,” she says. “But I’d have to memorize the piece in advance. Then I could follow the music. If anybody had ever said, ‘You, stand up and play that thing,’ I would have been found out.

“At the time I just thought I was a dumb person who could not understand theory,” she recalls. “I can see now that obviously I was meant for another path. I’m just saying that’s how I felt at the time, like an imposter. When I started playing in bands, I stopped feeling like that and started feeling like, ‘Oh, there’s something I can actually do.’ Because apart from what I’m bad at, I’m really good at this other thing, which is improvising and listening and making things up—and obviously that’s served me much longer than feeling like a failure in orchestra.”

Even now, after years of creating and performing music as a respected figure on the Montreal scene, Moss still deals with that issue, albeit more successfully. “At no stage of the game do I know what note I’m playing or what key I’m in or anything like that,” she says. “If you put a piece of music in front of me, I can go, ‘OK, I understand,’ but I don’t know what key a thing is, and I mostly relate to the things I’m seeing as sense-memory finger stuff.”

Moss doesn’t really have a writing process, except when it comes time to start working on a recording. “Usually by then I have in my head—in my sleep, in my moments, in my body, in my mind—ideas for things that are inspiring me or preoccupying me, or something that I would like to try and express. By the time I go in to play, I know what I mean to express, and I’ll spend hours and hours improvising. I record everything that I improvise, and then I walk around and listen to all of it. Parts of it will start talking to me, like ‘Oh yeah, that does sound like approaching a lake,’ or ‘That does sound like the sadness I’m feeling right now.’ I start gathering the parts that speak, listening to them and weaving them together, and that is my writing process. Once they’re woven together, I learn them as though they were a piece of music, and once I do that, other things start asking me to leave them behind or add them. The best times are when I’m working on something that’s inside my head and all of a sudden it becomes something else. It’s exciting when that happens.”

Galaxy Heart is dark and strangely soothing, meditative and mesmerizing. When it ends, it suddenly feels like there’s a vacuum in the room, and you miss it. Some tracks, like “Light Falls on Every Door,” are sparse and sadly beautiful, but others, like “Uncanny Body” and the title track, add guitar, vocals, beats and crackles, bass and drums to the violin soundscape. “It was the first time I actually had other musicians play on my record,” Moss explains. “I worked with my dear and oldest musical collaborator, Thierry Amar, the bass player of Godspeed and Silver Mt. Zion. He really understands theory—the rules are fascinating and important to him, and he loves to know how a song works—and when I approached him with this music he was like, ‘How? How did you go from here to here?’ And I don’t know the answer. I don’t feel like I’m not supposed to do these things, but I definitely break a lot of rules.”

During her creative process, Moss thinks about the people she wants to collaborate with more than the instrument she wants to add to a track. On Galaxy Heart, for instance, she wanted to hear Jim White, the drummer of Dirty Three. “It wasn’t drums, it was Jim White that I heard, and the feeling of knowing him and loving him,” she says. “Probably if I asked a drummer I didn’t know or hadn’t worked with to play on something they’d be like, ‘What is this?’ I have this feeling that it’s completely opaque to somebody who needs rules. In the end, Jim sent me three beautiful tracks of drums for the violin study on Galaxy Heart, and I actually took parts from each of them. Same with Thierry. I recorded him and then I recorded me again. I really have to put my hands on it, if that makes sense.”

The hypnotic nature of drone music is one of the reasons Moss’s music is so enveloping. She first fell under its spell when she heard electric bassist Kevin Doria. “He’s one of the main reasons I started playing solo in the first place,” she says. “His band is called Growing, and he also played solo under the name Proto Life. He’s what I’d call a drone artist—he would fill the room with one note, and what we were listening to was everything around this big, incredible note. He came on tour with Silver Mt. Zion a few times, so night after night I heard him lift the room with this incredible gut-wrenching thing that he was doing.

“There’s a way to look at drone music like, it’s easy: you just play one note. In a weird way that’s true, anyone can do it, and it’s also true that you can hypnotize yourself just by really going into it. But with Kevin it was the intention and the care and the work that I could feel went into it. I’m a bit obsessed with intention—I get really upset when I think something is done carelessly or not because you have no choice but to express yourself in this way. I can love many different types of music if they have that intention, and I can hate some of the exact same music if I think somebody’s doing it because it’s easy or it’s cool or if I feel the guts aren’t in there.”

Listening to Doria’s playing made Moss realize how much she was attracted to drone—so much that she asked him if he wanted to work with her, and they began a virtual collaboration; Doria in Olympia, Washington, and Moss in Montreal. “It was the first time I went into the jam space by myself with my whole band setup, all my pedals, amps, everything,” she says. “I had his drones in my ears, and I was inventing what came to me to meet his drones and the space that they gave. And all of a sudden, I had this whole heart full of music. It started coming out—flying out. Only then did I realize that I could tell some kind of story by myself. That collaboration was a jumping-off point for me.”

This fall, in addition to Galaxy Heart, Moss will release a collaboration with Isak Goldschneider on the first-ever transcription of her compositions perform a series of shows across the eastern U.S. and Canada, and reunite with her old friends in Black Ox Orkestar for the first time in fifteen years to release a new album in November.

Black Ox Orkestar began as a quartet of Montreal musicians—Moss, Thierry Amar, Scott Levine Gilmore and Gabriel Levine—looking to explore their roots in Jewish music from Eastern Europe and the Balkans. They translated old songs from their own perspectives, wrote new material that encompassed klezmer and other traditional styles, and released two albums before breaking up in 2007, when Gilmore left Montreal.

“I was devastated; the whole band was devastated,” Moss says. “We weren’t able to talk about it and we never really did, we just kind of moved on with our lives. Cut to two summers ago, when we got an email from a journalist who wanted to write a feature for a New York magazine called Jewish Currents—maybe the only anti-Zionist super lefty print magazine out there. The feature was about whatever happened to Black Ox Orkestar, because this band was making radical Jewish music before that was something people did, and they had this idea that there was a new generation of political, engaged, anti-Zionist, lefty Jewish people who would want to know about this band.”

That caused the four members to connect for the first time in years, and one thing led to another. “We realized that we all felt unhappy with how it ended, and we started talking,” Moss says. “And it was during the pandemic and everything was happening virtually and remotely anyway, and so what if we had more things to say? And Scott started sending us demos and they were incredible. And we started working on them. Thierry and I would go into the studio in Montreal and add some things and Gabe in Toronto would add some things and it was a beautiful experience that led to—after many logistical difficulties—recording together. And so, with no expectations but the most beautiful of intentions, we got together and made this record, and it’s really good.”

Moss’s deep connection with klezmer music was strengthened on a Spring 2022 tour of Eastern Europe and the Balkans with Radwan Ghazi Moumneh, the producer and leader of Jerusalem In My Heart, who has engineered many of her albums. “He’s the person that I connect creatively with the most,” she says. “We were finally sharing a tour together after wanting to do it for many years, and we were in these countries that I’ve dreamed of going to, and my only regret is that I wish I could have spent more time in each city.

“My favourite music comes from that part of the world and my own Eastern European Jewish ancestry,” she says. “I had this weird feeling of body connection when I was there. It’s such a complicated history, and being there and knowing the heaviness of what everyone has lived through, really not that long ago. And still going on. When we played Belgrade, the show was put on by a promoter team that had relocated from Moscow. They left this well-appointed agency and came with nothing, and we were the first show they were putting on in Serbia. I can’t believe I get to experience stuff like that. It was incredible.”

Moss Transcribed

This fall Jessica Moss is embarking on a previously unthinkable collaborative project that will see her compositions transcribed for the first time and performed by a chamber orchestra.

Isak Goldschneider, musician, arranger, producer, and director of the Novarumori chamber ensemble and the Montreal concert series Innovations en concert, is working with Moss and the thirteen members of Novarumori to create seven arrangements of her compositions and perform them at a concert in Montreal at the end of October. But he’s also going further, developing additional arrangements for string quartet, orchestra, and even solo piano, that could open up more possibilities for performance.

“We’re looking at many different ways to build lenses that refract her work into different forms, but always being true to the spirit of the forms,” Goldschneider says. “The way I worked with Jessica’s music was just listening to it many, many times and making all kinds of mind maps and processes to recreate but also to expand and underline different elements of her scores. Some of the arrangements I’ve written are more open to improvisation and some are very strict in terms of the way they’re notated, and I’m looking for all kinds of different formats.

“I think of it as music that has a lot of soul,” he adds. “It’s one of the things I love about her work. It’s interesting because she is kind of an orchestra in her own right. And I love how she uses electronics as a solo performer with this amazing sense of melody, really this melodic genius—it’s not something you hear very often. She’s a pretty exciting artist, and I’m thrilled to be working with her.”

Goldschneider is also an admirer of klezmer, having played clarinet in klezmer ensembles in the U.S. and Montreal, and when he moved to Montreal one of the first things he bought was a Black Ox Orkestar CD. “What I find really interesting about klezmer, and I think Jessica really gets this, is that klezmer itself is an amalgam of many different musical styles,” he says. “It’s a kind of music that came out of the lived reality of Jewish people in Eastern Europe who were dealing with influences—some positive, some not—from many different cultures. Russian culture, Turkish culture, German culture—you hear all these different threads combining in the fabric of klezmer. That’s something I really hear in her work as well.”

Moss is thrilled at the thought of someone taking on the transcription of her music. “This,” she says, “is what I’ve dreamed of since I made my first record: ‘Imagine if somebody could listen to this and write it down! Imagine if it went from being in my head to being a physical thing like a score or a real piece of music!’ It’s so exciting.”

In the past, Moss thought such a project could never happen. “I would not know how to do it, beyond giving someone a track and saying, ‘Could you learn this by ear?’ Because that’s all I know; so it felt impossible. But Isak was so encouraging, he could do it by ear, he could listen to these things and work with them. And he’s coming up with arrangements for us to play with all these musicians.

“I have this dream of walking into a place and I wasn’t playing my music, I just got to listen to it. At least after this, this music will exist, which is amazing.”

FYI: The Novarumori chamber ensemble performed chamber arrangements of Jessica Moss’s compositions on October 29 at La Sala Rossa in Montreal. Black Ox Orkestar returns with a new album in November 2022, and will perform at the Music Gallery in Toronto on December 13 and at the Museum of Jewish Montreal on December 14, followed by shows in New Hampshire and Brooklyn, NY.

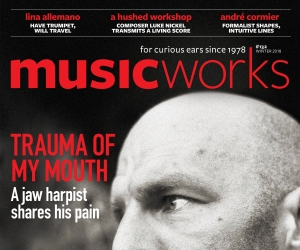

PHOTOS:

Photos of Jessica Moss by Stacy Lee.

Photos of Jessica Moss with Isak Goldschneider and Novarumori during rehearsals in Montreal, 2022 by Evan Shay / Nick Jewell Photo Services.