This article was originally published in Spring 2013.

The applause following the introduction of Akio Suzuki at his first Toronto performance since 1984 quickly died down to reveal an echo emerging from the concert-hall seats. It was a consistent pattering—not a true echo but a sonic answer to the applause. The source of the sound came from Suzuki, who was sitting humbly in the front row, tapping together two stones in his hands. After a few moments, he stood up and moved around the space in front of the stage, changing the rhythms and patterns of his tapping as he went. Most notably, he began to vary the quality of the sound by cupping his hands around the stones in different ways and by bringing the stones closer to his lips, where he created a small soundbox with his mouth.

The concert was a beautiful précis of the range of Suzuki’s interests and talents. He set up his instruments at various stations across the stage, moving from one to another. He focused his attention on smaller sound objects along the way: the aforementioned stones played a prominent role and he ended the show by creating sounds using a sponge on a metal plate. His performance illustrated his interest in the relation of acoustic sounds to the natural world, the thoughtful listening that he provoked in the audience, and a deep fascination with the power of the echo, the past-present-future of sound that plays a key role in his work. It is a central touchstone for the sonic universe that Suzuki explores. He talks fondly about the mountains of Japan and of how his many journeys on their pathways revealed to him the reverberant power of the echo.

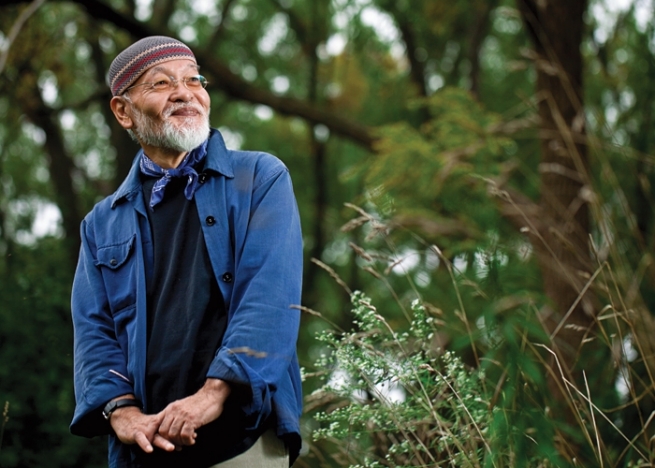

Born in 1941 in Pyongyang, Korea to Japanese parents, who moved their family back to Japan when he was four, Suzuki grew up in the Aichi prefecture, near Nagoya. After initially studying architecture, he turned toward sound. The ’60s found him in a period of self-study, initiated by the happening Kaidan ni Mono wo Nageru (Throwing Things at the Stairs) in 1963, where he threw a bucket of objects down the stairwell of the Nagoya train station. The movements of the time (Gutai, Fluxus, etc.) created an atmosphere for his experimentation, but Suzuki worked largely alone in the development of his ideas. The sonic details of that initial event—the live, raw sound of those objects falling down the stairwell and the reverberation of the architecture—became a central influence for his self-study, as he worked to follow the sound of the natural and manmade world and to develop ideas that would place him in relationship to that sound. All his work—from live improvisation to installations and instrument design—is based on an interest in the echo. The echo is the perfect example of the temporal continuum of nature. An echo brings the actions of the past into the present (for what is an echo but the mountains responding through repetition?), but also prepares for the future. It is a type of being-in-the-moment, which contains all sonic time.

Of the many instruments that Suzuki has designed, the Analapos is the one he continues to return to in order to further explore the possibilities of the echo. Originally designed in the 1970s, and modelled after a spring reverb, it is based on the design of a child’s toy telephone made by joining two tin cans together with a string, in this case connecting two large metal cylinders by a fifteen-foot spring wire. The Analapos is a cheeky response to the musical zeitgeist of that period; its humour extends to its name, a portmanteau of analog and postmodern. As Suzuki explains, “New technology was developing for music, where the echo became a futuristic thing during that time period.” But his personal interest stemmed from his interest in the natural world. “I used to play with echoes in mountains, then I invented the Analapos.” It is amusing to think that this simple instrument resembling a children’s toy competes effortlessly with complicated electronics designed to add special effects to disco and progressive rock, and that its very acoustic qualities draw from the sublime characteristics of the natural world.

Suzuki has one Analapos that he holds horizontally like an alpine horn to sing through, and a pair that are suspended vertically by a stand, so he can drum on the cylinder lids and the seven-foot spring suspended between them. The metal spring in between the two cylinders amplifies Suzuki’s voice and percussive hits to the cylinders, creating a rich and beguiling reverberation. To witness Suzuki in performance on the Analapos is to witness the way natural reverberation alters sound.

The Music Gallery presents: Akio Suzuki from The Music Gallery on Vimeo.

Through performance, Suzuki’s explorations concentrate on the acoustic properties of sound making. It is as if he is bringing nature into the hall—the simple resonance of two stones; percussion that sounds like a rainstorm; echoes like those heard on a valley floor. Suzuki, even at seventy years old, brings attention back to his interests as a child. In conversation he talks about his enjoyment of landscape, from watching from the window of his hilltop birth home in Pyongyang, North Korea to his afternoons spent in his house at Lake Biwa in Japan. “After it finished raining, the water flowed through the garden and I was always watching,” he recalls, “hearing and watching.”

Suzuki’s Hinatabokko no kukan (Space in the Sun), which was made over the course of the year in 1988, reflects his practice of hearing and watching, and was inspired by Debussy’s La Mer, a depiction of the ocean in sound. “I thought Debussy was sitting in front of the sea for a day,” Suzuki explains, “but I had never done such things before. I never used time like that before.” In fact, Suzuki later learned that Hokusai’s famous ukiyo-e woodblock painting of a wave had originally inspired Debussy to compose La Mer. This cross-pollination of inspiration between the East and the West is something that comes up often when discussing the range of Suzuki’s work.

Space in the Sun gestated in Suzuki’s thoughts for ten years, until he finally found the time and place to create the piece. On a quest up the 135th meridian east in Japan, Suzuki came across the Tango region outside of Kyoto and thought it a perfect spot to realize Space in the Sun. He negotiated with the locals to rent him a mountain and a small shelter to work from. For the next year he went back and forth from the shelter to the mountain, making earthen bricks using the sand and dirt from the mountain. He made 10,000 bricks, which he used to construct a brick floor seven meters long by seven meters wide. He then constructed two facing brick walls on opposites sides of the floor to create a space to focus the environmental sounds around him. Except for those two walls, the space was completely open to the elements.

After a year of building, Suzuki was able, on the autumn equinox, September 23, 1988, to sit down and listen all day from before sunrise to after sunset. In an interview with musician Aki Onda, Suzuki thoughtfully reflected, “I acquired through this bodily experience, the skill to become one with nature, like the trees that surrounded me.” He sat there, exhausted after a year of work, especially attuned to the surroundings in which he had spent so much physical labour. He was finally able to listen.

Space in the Sun resonates beyond its location because it illustrates the idea of building a space for the privilege to listen unabated to the natural world. With it, Suzuki claimed a space and directed his own listening. Although Space in the Sun is in disrepair, it still exists for sonic pilgrims who want a space for their own listening. While the end product is fascinating—the idea of sitting for a day in one place to listen to the world—the amount of labour that it took to build it is of equal importance in Suzuki’s work. Suzuki’s art is also about the work that he does to get to this place of listening. The piece, although we initially only recognize it at its stopping point, has a compositional relationship between movement and rest. The composition is the movement, the act of its making, the creation of space where there can be a rest.

The idea of movement and rest in Suzuki’s work is apparent in his installation oto-date, first created for the Sonambiente Festival in Berlin in 1996, at the invitation of Matthias Osterwold, the curator of the festival. Suzuki went to Berlin to create the installation and, not content to install his work in a gallery, decided to explore the central island of Berlin, called Museumsinsel, and to create a work out of these wanderings. He got the idea for oto-date by drawing on his earlier interest in searching out echo points in nature. “The capital had changed from Bonn to Berlin, so there was a huge building rush, with the city building lots of buildings during that time,” Suzuki explains. “There were cranes. So many constructions. It was a nice point in time to present oto-date . . . For me, the landscape, the natural world, is a focus, but everything is as it is—cities, too. Cities, cars, are noises. That also has a nice rhythm. For me the noises from the car are also a natural rhythm.”

The name oto-date derives from wordplay that Suzuki explained in the catalogue of a 2009 exhibit in Ichinomiya City: “In Japanese, nodate is a tea ceremony held in the open air. [On the basis of] that elegant concept, I suggested that the process of listening to the sounds of an urban environment could be called oto-date, incorporating the Japanese word for sound, oto.” For oto-date, Suzuki wandered about the central island of Berlin looking for listening points. Over the course of his time there, he found twenty-five points from which to listen to the city. On each spot, Suzuki stencilled a circle with a drawing inside it of two ears, positioned like footprints, inviting the listener to stand there and contemplate the surroundings. Since it is a cityscape, the sounds always change. Suzuki made sure that some of the points were referential and humorous evocations of the change of sound over time. One stencil was put on a manhole cover, with the expectation that its orientation would change whenever someone had to do work underground. Another was only accessible during dry weather.

“I found a very good echo point in Berlin,” Suzuki explains. “After a few days, I came back to spray the stencil, but because it had rained, there were ten centimeters of water there. But after all the water dried up I sprayed there. So, people who visit there after a rainy day, they will be surprised or confused.”

This sense of humour also shows how the piece opens itself up to the audience, allowing for an easy passage into the contemplation of the city’s soundscape. “Even residents of the city will find new places in the city,” says Suzuki, reflecting on the audience’s experience of the piece. “In the process of going to a spot, people find a different street. In a festival, I place the echo point and ask people to come and stop, but actually I create my work by wandering, and I want to share this sense of adventure with the people.” The compositional process of creating the work is as important as the points where Suzuki asks the audience to stop and listen.

The wide range of sonic experience that a listener hears when experiencing oto-date brings to mind the work of John Cage. “In regard to oto-date, I was influenced by John Cage,” Suzuki says. “Especially his chance listening. oto-date is a musical piece. Normally, a musical piece is five lines and dots—a score. My score is this big field where people come and stop and then they listen and compose music by themselves with the surroundings. Each person hears something different and there are many various ways of listening.”

In fact, John Cage was also a visual reference point for the oto-date. The ears that look like footprints, which Suzuki draws in the circle he paints on the ground to designate a listening point, are modelled on Cage’s ears, which Suzuki sketched from real life. As he explains, “The first time I was in New York, I spent time with John Cage and the Merce Cunningham dance company. We went to [put on] a performance in the Canary Islands. While we were waiting in the Kennedy airport, I had the time to sketch John Cage’s left ear. It was very important to me, so I always brought that sketch everywhere.” At Somnabiente, he finally had the chance to use that image, by making it into the symbol for a listening point.

Suzuki is very clear about his sense of the visual world in relationship to sound. As well as being a sound artist, he is also a practicing visual artist, so while a concert audience may privilege the hearing of it, the visual aspect of it is also very important. This is apparent in the minimal, striking designs of his instruments and the beautiful brick walls of Space in the Sun. It is also quite clear in oto-date, which not only opens up a sonic space, but also frames vistas of a city changing before the viewer’s very eyes.

Suzuki explains his relationship to the visual world in these terms: “Any kind of living thing sleeps at night and wakes up in the daytime, so life and living means open eyes. I want people to open their eyes when they listen. Sometimes in a concert, people close their eyes and listen only to the sound—to try to listen to pure sound. But I want the audience to use all their senses. I want people to open their senses, open their eyes, and feel their total surroundings.”

With Suzuki’s work, it is clear that we attend to our surroundings at the same time as we listen to him. His acoustic instruments, with their striking simplicity and visual purity, blend strongly into the world, whether he is performing on a stage or in an outdoor environment. He asks us to stop and listen to that world, whether aided by his live performance or guided by the points on the landscape that he marks out for us. His listening practice, like Cage’s, extends beyond the music to a philosophy of hearing and watching. That philosophy absorbs the ever-changing environment as if it were a score, allowing sound to accumulate and reverberate, to echo through our lives.