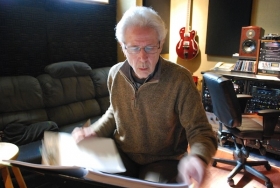

The imagination of electronic composer John Mills-Cockell exists in a liminal space. His music, with its neon-pastoral glow, feels neither jarringly futuristic nor soothingly nostalgic. Nevertheless, as the very first Canadian owner of a Moog synthesizer (purchased the same day Wendy Carlos bought hers from creator Robert Moog in Trumansburg, New York), Mills-Cockell is rightly regarded as part of the vanguard. The premiere of his Moog in a three-night run at the Art Gallery of Ontario in 1968 was the world’s first live performance of music made by a synth.

Mills-Cockell’s work traces a continuum from his late-1960s sensory-overload multimedia collective Intersystems to the melodic genre-hybrids of his early-’70s instrumental trio Syrinx. This work flows seamlessly from collaborations with such artists as Kensington Market, Anne Murray, and Bruce Cockburn, into solo ventures in ambient music and progressive rock, plus decades of celebrated scores for theatre, film, and television. The seventy-three-year-old composer’s output spans a vast sonic territory, yet he views it all as an ongoing Star Trek-like quest to explore strange new worlds.

This astral body of work is being reexplored and celebrated in a three-part, nine-record compilation that Mills-Cockell has dubbed “JMC Retrospective” on his Web site. Covering his recordings from 1967 to 1977, it involves releases by three different record companies. The project was launched in 2015 with Italian label Alga Marghen’s release of Intersystems, a blockbuster box set, in both vinyl and CD formats, of the Toronto collective’s three albums: Number One Intersystems, Peachy, and the cheekily titled Free Psychedelic Poster Inside (there never was one). The vinyl versions are each available on their own; the CD box contains a twenty-six-page booklet; and the three-LP package comes with a 132-page book of essays, poems, press clippings, and photos. For old fans of Intersystems or fresh ears to it, this weighty tome delves more deeply into the group's bag of tricks than anything that’s come before.

In October 2016, the New York-based label RVNG Intl. released Tumblers From The Vault, another three-album set (optional three-LP, two-CD, or digital download), this time featuring the music of the synth-sax-and-percussion trio Syrinx. The band's beloved self-titled debut and its sequel Long Lost Relatives are joined by a third disc of previously unreleased, rarely heard oddities. RVNG presents Syrinx’s music in a modern context, with stylish new packaging and fantastic liner notes from Musicworks contributing editor Nick Storring, whose writing also appears in the Intersystems companion volume. A planned Syrinx documentary film by Zoe Kirk-Gushowaty will tell the visual story, and Mills-Cockell is preparing to revisit the group’s music in live performances this spring.

The third component of the project, with title and label pending, is being shepherded by producer William Blakeney, who conceived the overall project. This concluding set of CDs will include selections from Mills-Cockell’s 1970s solo recordings, soundtracks, and more.

Sifting through these archives, resurrecting the name Intersystems for a pair of new studio projects completed in 2016 and entitled Unfinished World and Network, and preparing to perform Syrinx’s music live for the first time in decades, Mills-Cockell is taking a break from the complex arrangements of his commissioned pieces, joyfully revisiting the spontaneous improvisation of his earliest work.

“There were things I was doing with the synthesizer in the days of Intersystems that I wish I had stuck to more,” Mills-Cockell says, from his home on Vancouver Island. “Using pure electronic sounds and not trying to be ‘musical’ has become of much greater interest. I started with a love of sounds critics would describe as bleeps and squeals and think there was nothing there. That sensibility might not be with us so much anymore, but all of my work is intuitive. If it starts to become too organized and ordered, it’s somehow not as successful.”

Mills-Cockell’s creative career is rooted in off-kilter adolescent impulses. At fourteen, rather than plugging in with a rock group in his garage, he discovered jazz and formed a duo with trombonist Russ Little. Inspired by Benny Goodman and Miles Davis’ Milestones, the pair jammed every day in Mills-Cockell’s basement. “That was what we did before going out to play hockey,” he laughs. “Russ’s trick was ‘name any song and I’ll play it as fast as I can.’ He’s still like that today.”

In 1958 Mills-Cockell’s father and stepmother, finding their son’s burgeoning interests becoming audible, arranged for him to live in England, working in the music section at Harrods in London. The luxury-department-store staff invited Mills-Cockell to a BBC Proms concert at Royal Albert Hall, which inspired an epiphany.

“When the musicians left the stage, there were two loudspeakers,” he remembers. “A guy in a lab coat came out and said they were going to play Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Studie I. He left the stage and nothing happened for a while. Then he came back and said, ‘We didn’t get the tape! We do have another piece by a Canadian composer named Hugh Le Caine—Dripsody.’ He left the stage again and these amazing sounds emerged. I was drop-jawed: ‘This is what I want to do for the rest of my life!’”

The musique concrète of Le Caine’s leaky faucet released a torrent of possibilities in Mills-Cockell’s mind. Yet, at age fifteen he still had two years of high school. This offered ample time for daydreams of wires before enrolling in the University of Toronto’s music education program. When Mills-Cockell mentioned Dripsody in class, his instructor Dr. Myron Schaeffer revealed that he oversaw an electronic music studio. Accompanying Schaeffer to a Victorian building on Huron Street, Mills-Cockell excitedly entered its ramshackle radiophonic workshop. Dr. Schaeffer urged him to assemble a beginner’s toolkit of half-track tape recorders wired together with an amplifier. Adding a tone generator and microphone, he was off to the races with another inspiration few would consider musical.

“I was living on Spadina and had just married,” Mills-Cockell recalls. “I would hang my microphone out the window where the streetcars would go by Knox Presbyterian Church. Back then, the wheels and rails made an incredible squealing noise, and that was my first sound source. I changed the speed, transferring it back and forth until it got more distorted. You can actually hear me reference that on the first Intersystems album, with a lyric about eight metal wheels squealing.”

Mills-Cockell switched his major to piano and composition at the Royal Conservatory of Music, while continuing seminars in electronic music with Gustav Ciamaga at U of T. In 1968 he earned a BMI student composition award for Fragments for Orchestra, Study for Bassoon, Prepared Piano and Magnetic Tape. Udo Kasemets then commissioned two more of Mills-Cockell’s pieces for a concert with trombonist Stuart Dempster, featuring works by Pauline Oliveros, David Tudor, and Gordon Mumma.

Most importantly, Mills-Cockell and his classmate, the late composer Ann Southam, assisted in a DIY electronics course in the basement studio operated by instructor Samuel Dolin. Intersystems members Michael Hayden and Blake Parker and Syrinx member Alan Wells attended the first day of this ten-dollar walk-in class, introducing Mills-Cockell to three lifelong collaborators.

U of T’s Perception ’67 psychedelic art festival was the next major event on Mills-Cockell’s time line. Alongside luminaries Allen Ginsberg, The Fugs, and Timothy Leary (who was blocked at the border but able to hand over a videotape of his talk to a student on the Rainbow Bridge) this weekend happening spawned Intersystems. Mills-Cockell was enlisted as the electroacoustic sound-sculptor, joining poet Blake Parker, architect Dik Zander, and installation artist and ringleader Michael Hayden.

[PHOTO LEFT TO RIGHT: Blake Parker, John Mills-Cockell, Dik Zander, and Michael Haden of Intersystems, 1968.]

“The original inspiration for the group was to get me out of the hot water I had found myself in by declaring I could make an environmental installation that would emulate the experiences of a psychotropic event,” laughs Hayden. He is currently completing a 600-foot LED sculpture at Yorkdale subway station, continuing five decades of large-scale interactive art. Intersystems’ first project was the Mind Excursion, filling ten rooms with what Mills-Cockell describes as “a funhouse of sights, sounds, and smells.” This included a chocolate room with edible walls, a four-foot room with distorted faces gazing upwards, fluorescent confetti frozen midair by pulsating strobes, and cotton cloud-beds floating above an airborne city. Mills-Cockell’s mind-warping tape experiments and Parker’s deadpan narration filtered throughout this immersive trip.

The next two years saw Intersystems invited to mastermind more self-described “presentations” in Vancouver, New York, and Pittsburgh. Their proto-Internet game Network toyed with the transmission of multimedia messages through TVs and telephones, with players consulting a mandala-like chart. It was unveiled in Washington and captured the attention of R. Buckminster Fuller, who invited them to his Southern Illinois University.

The group’s work culminated in Montreal’s Mind Excursion Centre, a far more ambitious update to its predecessor, with months of preparation and a budget in the hundreds of thousands. “It was our largest project and the one fire marshals approved of,” says Hayden. “There were floating rooms and a mirrored room where you walked down the corridor of a kaleidoscope.”

Prior to the adoption of Mills-Cockell’s Moog, the group recorded their first album Number One Intersystems, with homemade devices such as “The Coffin.” This satin-lined box was the resting place for piano wire, tuning pegs, and contact mikes used to switch between ghostly samples, like a radio station from beyond. Its ominous acousmatics combine with scraping strings, hypnotic drones, and Parker’s Burroughsian cut-ups on the album’s signature song “Orange Juice & Velvet Underwear.” As Nick Storring writes in the book that’s in the box set, “they embraced psychosis, lust, hilarity, and, conversely, profound mundanity.”

Peachy (1967) utilized the synthesizer to even stranger effect. Parker’s grim voice floats above jump cuts of electronic crickets, exterminating Daleks, and haunted ballroom music that would make Leyland Kirby perk up his ears. Intersystems’ final album, Free Psychedelic Poster Inside, was created as the soundtrack for the Mind Excursion Centre, with each room containing a chapter of this domestic soap opera starring the doomed couple Gordy and Renee. Of course, it comes complete with woozy stereo pans and sine waves designed to drill into your skull.

“What we were doing was folk music,” says Mills-Cockell. “Blake’s poems are everyday stories and the sound is found art. We didn’t find it in junkyards, but we were always going through electronic stores selling clear-out circuitry. We were banging on instruments that we could barely keep in tune, or even wanted to.”

“People take Intersystems seriously, but not Blake’s poems,” he continues. “The flatness of the delivery makes them feel like artifacts rather than reality. On Peachy, there’s the allegory of finding guns and shooting pigs. It’s just as resonant now, if not more so. At the same time, he’s literally reading things from the newspaper. He tells the story of a man executed in prison in New York State. Like Andy Warhol did with his paintings, Blake took mundane things from life and iconized them.”

[PHOTO LEFT TO RIGHT: Alan Wells, John Mills-Cockell, and Douglas Pringle of Syrinx.]

Electronic flourishes from Mills-Cockell’s Moog flesh out Toronto band Kensington Market’s 1969 album Aardvark, during which the synth player met producer Felix Pappalardi, famed for his work on Cream’s Disraeli Gears. Pappalardi signed the keyboardist to his management firm and set him up with solo studio time on the West Coast. Mills-Cockell packed up an Econoline van and drove from Toronto to Vancouver with his wife and their young child to begin the recordings that would become Syrinx.

After completing these sessions with conga playing by Alan Wells, Mills-Cockell trekked back to the U of T campus for a gig at the restaurant Meat and Potatoes. The improvised music he created there certainly did not reflect the name of the venue. He was unexpectedly joined by saxophonist Doug Pringle, who was schooled in free jazz with groups such as the Kinetic Improvisation Ensemble, and who also performed at Perception ’67. The two musicians immediately clicked.

After several months of supper-hour gigs, which attracted a coterie of followers, the pair moved into Pringle’s loft, where like-minded musicians, actors, dancers, painters, writers, and filmmakers surrounded them. “Sometimes we would have to kick people out so we could get some work done,” Mills-Cockell says. Pringle added slinky sax to earlier recordings of Mills-Cockell and Wells, who himself returned from the West Coast. Kensington Market manager Bernie Finkelstein signed the group to his label True North Records, and Syrinx was born.

The trio’s 1970 debut shifts subtly in mood from the idyllic “Field Hymn” to the majestic “Chant For Your Dragon King.” The impressionist influence of Debussy’s tone poems can be heard on the highlight “Hollywood Dream Trip.” The closing track, “Appaloosa-Pegasus,” hints at the high-spirited sounds the trio would explore in future recordings, with a brisker pace and Mills-Cockell’s burbling solos. Bart Schoales’ vibrant cover art was the cherry on top of their psychedelic sundae.

“I came from a background of electronic music that wasn’t pop or bleeding-edge avant-garde,” says Mills-Cockell. “Doug came from post-Ornette Coleman, post-Albert Ayler free jazz. Alan was a street drummer playing bongos in the park. It was utterly simple and utterly tuned in at the same time. Our unique combination of instrumentation worked amazingly.”

A fertile period of creative cross-pollination saw Syrinx work with everyone from claymation company Laff Arts (which became Nelvana) to the National Ballet and director David Cronenberg. In addition to sharing stages with Ravi Shankar and Bitches Brew-era Miles Davis (“We talked a bit but he was pretty surly,” says Mills-Cockell), they joined magician Doug Henning for a weekly residency at Le Hibou in Ottawa. Before his Broadway hit Spellbound, Henning sawed a woman in half to the sounds of Syrinx.

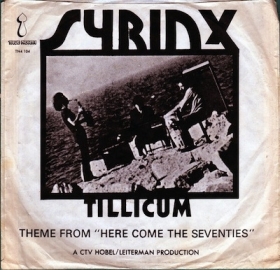

The group’s best-known commission is “Tillicum,” one minute and fifty-eight seconds of sputtering synth-pop created as the theme song for CBC’s Here Come The Seventies . The TV show’s omnipresence between 1970 and 1973 led to the piece being released as a seven-inch single, which hit #38 on the national charts. It could be considered a Canadian counterpart to Delia Derbyshire’s Doctor Who theme or Van Der Graaf Generator’s version of George Martin’s “Theme One” (the former BBC Radio 1 fanfare theme).

“We recorded ‘Tillicum’ twice, because the CBC had suggestions about how it could be better,” remembers Mills-Cockell. “They said it was kind of sad, because it was in a minor key, and that it could be faster. I was grumpy, but I said, ‘Yeah, I guess so.’ We went into the studio at nine the next morning, drank a bottle of rosé and recorded the song in two takes, as fast as we could.”

“I played my horn at night on the back deck of my loft,” recalls Pringle. “The moment we knew we had made it was when we could hear ‘Tillicum’ being played back from the taxi depot across the street on CHUM radio.”

But after Syrinx began recording their second album, Long Lost Relatives, tragedy struck: a fire in the studio destroyed the band’s equipment. A benefit concert featuring Bruce Cockburn, Beverly Glenn-Copeland, and April Wine raised more than enough funds for them to retool. Mills-Cockell used this windfall to purchase new toys, including an ARP synthesizer, a Vox organ, and an EMS Synthi Hi-Fli.

“That would have been a terrible end to the band, but these things happen,” Pringle says. “It was a sort of cosmic intervention. When the truck arrived with our shiny new equipment, it was a great day.”

“We decided to dust ourselves off, pick ourselves up, and keep going,” Mills-Cockell echoes. “I don’t remember any gap.”

During a trip to Myrtle Beach in South Carolina, Mills-Cockell wrote the score for Stringspace while gazing at the ocean from a hotel window. This dazzling symphonic suite, with Milton Barnes conducting the Toronto Repertory Orchestra, became the centrepiece of Syrinx’s second album, Long Lost Relatives. Mills-Cockell’s synthesized flurries, Pringle’s effects-laden sax, and Wells’ tumbling percussion match the intensity of the orchestral backdrop. A second live performance was televised, and audio from this stirring version is included on the RVNG reissue.

“When you have an audience that defined and committed, you play well,” says Pringle, who later cofounded arty synth-punk group The Poles with his partner Michaele Jordana. “It’s the same as punk. People got so elevated and lifted up from the vibe in the room.”

RVNG’s disc of rarities, Long Lost Relics, includes extended solo-synth workouts of “Melina’s Torch” and “December Angel.” An alternate vocal version of “Better Deaf And Dumb From The First” reveals a remnant of Syrinx’s final period, as a quartet with drummer and singer Malcolm Tomlinson. This incarnation opened for Deep Purple and played to a crowd of 150,000 at the Strawberry Fields festival.

“It was in the middle of the day, and when I walked out on a stage like that, for the first few minutes I was shaking,” Pringle recalls. “Then one guy down in the front row said something and I realized they were all real people out there.”

These moments from the band’s history might have been lost forever without renewed interest from RVNG founder Matthew Werth, who grew up with punk rock in Little Rock, Arkansas, and arrived in New York well before avant-garde inclinations took hold. He added Syrinx to his label’s reissue roster of L.A. performance artist Breadwoman, German kosmische synthesist Harald Groskopf, and Italian prog group Sensation’s Fix. Werth discovered Syrinx during the aughts via the influential music blog Mutant Sounds. “I went right past the fringe elements and felt a strong melodic, emotional quality,” says Werth. “That might be different than other people’s experiences. For me, it felt like it came from a very intentionally musical place. Syrinx crafted engaging compositions and then blew them apart with processed sax, crazy percussion, and bonked-out synth lines.”

Part three of the JMC Retrospective, which is nearing completion, has involved the exhaustive unearthing of archival material, supervised by producer William Blakeney. Alongside selections from Mills-Cockell’s solo albums Heartbeat, A Third Testament, and Gateway, the project includes the original lost album Neon Accelerando. The set is rounded out with rare demos, scores from BBC television shows, dance performances, and horror films, and even some surprising covers: Stan Jones’ “Ghost Riders in the Sky,” Joe Meek’s “Telstar,” and Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony channelled on fuzz guitar by Gene Martynec.

Mills-Cockell and Blakeney have also been working at Grant Avenue Studio in Hamilton, Ontario, on two new Intersystems albums, tentatively set for release in 2017 by Alga Marghen. Unfinished World features digital realizations of poems by the late Blake Parker with a soundtrack of vintage Moogs, Mellotron, and a massive 4U system designed by famed electronics engineer Roger Arrick. “I think Unfinished World will be a candidate for the weirdest synth album to ever come out of Canada,” says Blakeney. “One listen to the tracks and you will be hearing fragments of Blake Parker’s narratives for the rest of your life. But if it wasn’t disturbing and profoundly weird, it wouldn’t be Intersystems.”

Network, which revisits the group’s 1967 game of the same name, features a dense collage of 1960s commercials, news programs, and game shows. Mills-Cockell’s electronic score accompanies hundreds of voices in a multitude of languages discussing the topic of psychedelic drug use, all viewed through a post-Marshall McLuhan lens. “It was an incredibly hot topic at that time, like fentanyl is now,” says Mills-Cockell. “The difference is that I don’t think there was a dire danger associated with psychedelics. There was intent to make them sound sensational, but people weren’t dying on the street every day from taking LSD.”

Michael Hayden, whose guiding hand is present in the artwork for the Intersystems albums covers, is also collaborating with Mills-Cockell and Québecoise librettist France Ducasse on the opera Kid Catastrophe. Syrinx live performances in 2017 include an appearance at Moogfest in Durham, North Carolina, in May. With orchestral accompaniment and perhaps a few familiar faces, Mills-Cockell’s electronic imagination not only endures but continues to evolve.

“Music should not be fossilized,” Werth says. “It should be given a chance to reanimate or reactivate. It’s more of a classical-music approach to think how it could be reinterpreted by other people hundreds of years after it was composed. If artists aren’t beholden to a certain time, there’s an opportunity to celebrate the entirety of a musician’s career instead of just a single part.”

FYI: Syrinx regroups at Moogfest (May 18 to 21, Durham, North Carolina) with John Mills-Cockell joined by Toronto percussionist Rick Shadrach Lazar, Waterloo sax virtuoso Willem Moolenbeek. The trio will rehearse in Hamilaton and hopes to play Canadian dates in 2017.

FYI: Canadian comics artist Ken Steacy created "Pangalactic Performer"(HOMEPAGE SLIDE, ALSO IN PRINT ISSUE #127) when he was working on his first graphic novel, The Sacred & the Profane: “My collaborator Dean Motter was a serious audiophile who introduced me to all kinds of amazing work, including that of John Mills-Cockell. I didn’t meet John til much later, but I did get to know Bart Schoales, who designed Syrinx LPs, and John’s later solo concept albums. Dean and I were both so enamoured with JMC’s work that we patterned a character after him. That was the genesis of the image, which is essentially a character / costume study. We completed the black-and-white version of the story, then ten years later revamped the whole shebang in full colour, first serialized in Marvel Comics’ EPIC Magazine, then as an anthology published by Eclipse Comics. But by then our musical taste had shifted, and we modelled JMC's character after John Foxx (Ultravoxx).”

All photos by Bart Schoales, except bottom portrait of John Mills-Cockell (in 2015) by Rob Fantinato.