Chloe Alexandra Thompson has always thought of sound as something visceral. “I think, if I trace it back, my first sound installation happened when I discovered that the fabric in front of loudspeakers could move from the sound vibrations,” she tells me. “I just freaked out and started building this string situation in the living room, folding pieces of paper into tents and placing them on the speakers to watch them vibrate. I was probably five or six years old at the time.”

We’re on a video call in July 2022—I in Toronto, and Thompson in Brooklyn, New York, where she’s now based. A Cree Canadian interdisciplinary artist and sound designer, Thompson bridges installation, composition, music technology, and live performance in her practice, often working with high-density arrays of loudspeakers to craft site-specific, immersive electronic music. She’s fresh off the June release of They Can Never Burn the Stars—a collection of music she created in December 2020 in residence at the New York-based centre Pioneer Works, on the Washington-based label SIGE Records—and preparing for upcoming appearances at Montreal’s MUTEK Festival and the Time-Based Art (TBA) Festival at Portland Institute for Contemporary Art, as well as independent sound-design and composition projects for television and film.

As a performer, Thompson has built a modular, often minimalist practice, combining computer programming with sensors and controllers to create dark, liquid-like sets of music that seem capable of bubbling up and adapting to the size and shape of a particular room. Using her background in both computer science and interdisciplinary art, she has worked with AI, coding, and virtual reality platforms to create interactive, virtual sound-environments. Her sonic explorations treat the hardware and loudspeakers she uses not only as a playback system, but as instruments engaged in questions of ethics and acoustics that resonate with the spaces they inhabit and the people who visit them.

“I guess I’ve always been interested in sound and music,” she says, speaking about the living-room experiments of her childhood. “I realized that sound was a force to be reckoned with.”

Thompson spent her adolescence and young adulthood in the Pacific Northwest—first in Vancouver, where she played and organized live shows in the DIY music scene, and later in Portland, Oregon, where she began to create and exhibit work independently as an interdisciplinary artist. While in Portland, she frequently incorporated sound components in her visual artwork and poems; she also taught herself creative coding and began to create as a sound designer and composer for dance.

She acquired the technical tools for electronic music-making primarily through self-directed learning, mentorship, and on-the-job training. “I left home at a young age, so apart from playing clarinet and singing in choirs growing up, I didn’t study music in school, outside of audio programming” she explains. “I was just out in the world: helping put on shows, interviewing artists for a magazine, learning to set up speaker systems, asking too many questions.”

Thompson’s current artistic practice has grown directly out of her background as a technician; she teases out the different physical and spatial phenomena that can be crafted with electronic sound. In some of her projects, she works with techniques like wavefield synthesis—a form of spatial audio that creates virtual acoustic environments—to play with the audience’s perception of space. In others, she homes in on the physicality of the loudspeaker itself, playing with the acoustic and otoacoustic phenomena that can arise from working with certain combinations of sounds, or from pushing speaker technology to a breaking point.

Moiré, Thompson’s collaboration with Portland-based multidisciplinary artist aesthetic.stalemate (Matthew Edwards), was released in 2021 by Sounds et al. as both a six-track audio album and a downloadable interactive virtual environment. Its title is a reference to moiré patterns, large-scale interference patterns produced when two almost-identical lines, images, or waves are overlaid one on the other, analogously to the beating rhythms heard when two frequencies are slightly displaced or differently tuned. Thompson and aesthetic.stalemate first presented Moiré at the Portland Art Museum’s live cinema series Undertones in August 2019, followed by a performance of the same name at MUTEK and a VR installation at Video Pool in Winnipeg later that year. Moiré has since become a recurring theme in their work together. Thompson is interested in glitch and in error. “I’m just sort of teasing at the kind of inadequacy, to some extent, of the work that I’m doing, as well as these mediated forms of listening that we have.”

Like Moiré, Thompson’s 2022 solo release They Can Never Burn the Stars blurs the lines between the act of music-making and the space it’s made in. The final track, “Touch Modality,” composed for fourteen subwoofers, is a documentation of extremely low frequencies, recorded through hydrophones and transmitted at a high volume—fifteen minutes of shifting, low drones, some of them at the border of audibility. One can also feel several layers of ultra-low noise, inaudible through standard loudspeakers but somehow still present: like the electric energy in the air before a thunderstorm. A higher-pitched, soft clattering comes in and out of focus in the soundscape; that’s the noise of the objects in the room rattling from the sound vibrations, Thompson tells me. On laptop or phone loudspeakers, this rattling is often the only sound that can be heard.

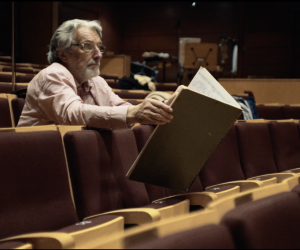

Thompson’s music often can be characterized as sound installation—even when it’s presented in the form of a live performance or concert. For her live shows, she prefers to spend multiple days preparing in the performance space, tuning her music to the acoustics of the room, and planning out musical structures that comprise both precomposed and improvised elements.

“Site-specific installation—responding to an architecture or a lack thereof—is exactly the same as spatial audio to me, it’s about using the loudspeakers in a room to create a different acoustemology than what might otherwise exist,” she says. “I can use software to digitally record the audio that I’m producing on my computer, but that’s actually not what I’m hearing: what I’m hearing is that sound responding to whatever sound system I’m using, and that response to the space that it’s in.”

During her album release show for They Can Never Burn the Stars, Thompson had an issue with her monitors and couldn’t hear the music she was performing. “I couldn’t hear anything that was happening in the house—the noise from the monitors was so loud that nothing else existed for me,” she recalls. “But when I looked out to the audience, people looked relaxed and were closing their eyes and smiling. I realized that whatever I was hearing was completely different from what they were experiencing. I just leaned into that, and threw the plan out the window and improvised, based on how I saw and felt people responding to the sounds that I was making.

“It was this moment of really remembering that good improvisation is about reciprocity,” she continues. “There’s this unspoken contract [with the people in a performance space] where we’re engaging in this exchange, where we’re working together. And if you can hold that connection, hopefully it becomes mutually beneficial.”

Thompson strives across her practice to maintain flexibility and a sensitivity to context as a community organizer, a composer, and an improviser. As a consortium member of First Nations Performing Arts (FNPA), Thompson works with other U.S.-based First Nations artists and arts administrators to build more sustainable, respectful relationships between arts organizations and the Indigenous artists and communities they work with. The project has three Convening Tracks for dialogue: Kinship Work supports connection and collaboration between Indigenous artists and arts workers; Network Track aims to define the consortium’s own goals and the ways it can best support the needs of the FNPA community; and a Decolonizing Track focuses on long-term coursework, consultation, and assessment with settler institutions to work towards more reciprocal relationships with Indigenous people and the Indigenous lands where they are based. In September 2022, Thompson attends the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art’s Time-Based Art Festival for the second in-person convening of the FNPA, in a performance gathering of artists from the consortium’s network. She is also performing there, working with material from They Can Never Burn the Stars to co-create a generative, audiovisual work with Pacific Islander artist DB Amorin.

In many ways, Thompson has built her work around these ideas of music as a site for investigating new forms of being, and for building new relationships of respect. Sound, she explains, is something that situates us—and spatial audio can be a particularly fraught space when considering issues of agency and access.

“When wavefield synthesis is done to a high level, it’s kind of as if you put invisible laser-beamed headphones on the audience. headphones. It’s very directional, and very concentrated, and it can produce a great amount of anxiety,” she says. “In guiding those experiences, you have to consider that the sound object is a host of this material that you are approaching people with in a very physical way—and that if you look back at the history of sound and musical practice—and its relation to our survival instincts, to ceremony, and also how it’s been weaponized—there’s a lot of meaning there.

“I really do base my practice on response,” she adds, “and on how sound is in the real world.”

Sifting through Thompson’s work, I keep returning to “Touch Modality”—the sub-bass-only track from They Can Never Burn the Stars that, depending on which speakers I listen with sounds either like an ominous procession of deep drones or like almost nothing at all. Even when played quietly on laptop speakers, when all I can make out is an occasional faint rattle, it’s as though the invisible presence of those low, impossible vibrations finds a way to make itself known and felt.

“I was using hydrophones in tubs of water to record that piece, and we could see these cymatic effects, where the water would go into these standing patterns from the sound pressure,” Thompson tells me. “We were all wearing hearing protection, but you could still feel it in your body. And if you look at the water, and you think about how we’re made up of sixty-odd per cent water—our bodies’ water is also doing these things. We went home after that recording; and that night everyone had the most vivid dreams.”

In Thompson’s compositions, you can hear her sensitivity to sound as phenomena, to music as something that impacts us emotionally and physically, and to the body as a receptor that can attune itself to the minute details of a space or a noise or a musical moment, if we prompt it to.

“There’s a power that resides in sound that allows us to communicate what words might lack at times,” she says. “It’s something to be dealt with with care—but it’s really beautiful, too.”

AUDIO: An Exchange (2022) 05:15 Composed and performed by Chloe Alexandra Thompson. From her album They Can Never Burn the Stars (Side Records, SIGE 108), released June 17, 2022. [Track also appears on the Musicworks 143 companion CD.]

PHOTOS:

Top two photos by Amelie Jackie.

Bottom photo: Chloe Alexandra Thompson (left) and aesthetic.stalemate performing at the 23rd MUTEK Festival in Montreal, August 2022. Photo by MUTEK / Myriam Ménard.