Pleasure Calls is a collaborative, interdisciplinary installation and performance by Camae Ayewa and Carmel Farahbakhsh that activates revolutionary ways of loving one another. The installation is the culmination of a week-long residency in early March of 2019 at the Khyber Centre for the Arts, an artist-run centre for noncommercial work located in the historic Halifax harbour area. The pair met serendipitously at the 2017 edition of Halifax’s Obey Convention festival, where Halifax-based Farahbakhsh opened for Philidelphia-based Ayewa’s avant Afrofuturist-activist solo project Moor Mother. They have since nurtured a strong and totally unique togetherness, resilient to physical separation, that draws upon legacies of ancestral care, self-devotion, and devotion to community and family.

“It’s good for [the Halifax community] to see how we can come together in a historical way, in a family way, in love of poetry and senses and smells and memories and things that are important to us,” Ayewa shares. “Carmel’s been able to see my community as this sort of global exchange, so it’s nice to make work here where they live.

“It’s not just a show for the people, but also a way to expose the inner and outer workings, since you can look back and see the things we’ve talked about and thought about and how we brought it all together.”

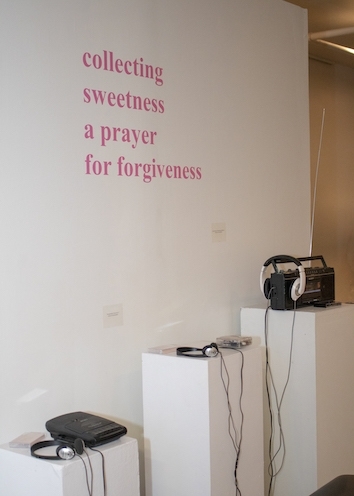

Farahbakhsh describes the installation as “artifacts of shared experiences that are pillars of comfort and safety built [during] a long-distance relationship.” The artists explore how sounds, scents, and images create and build memory across distance. “This residency was us creating a home for our sounds that was also an act of devotion to ourselves and each other in this space.”

Pleasure Calls sounds much like a love letter or diary entry left trustingly open. This was exemplified by the opening-night performance, during which they built an improvisation upon layers of their collected experiences. Ayewa’s poetry and signature synthesizers-and-samples playing combined with Farahbakhsh’s rich yet humble, classically trained electric-violin playing. Farahbakhsh’s singing in Farsi was presented like a personal form of worship song, at once devotional, rooted in tradition, and exploratory, contemporary, and including everything—all sounds and gestures equally welcome. “We created various altars and spaces of memory transportation that are rooted in home and family, and through those acts of devotion we create this call to ritual and call to self that we can share with the people we love.”

Farahbakhsh speaks to the radical aspects of pushing traditional forms, “So much of this work for me is about acts of prayer—not in a stereotypical way, but in the context of [asking] what does it mean to queer a prayer? What does it mean to hold prayer for people who are speaking a variety of languages and have many different relationships to faith? What does a prayer feel like? How does it transport us in and out of places of loving? How do we call that into sonic joyfulness?”

The task of “archiving significant memory as an act of healing the virtual limitations of time, distance, and borders” and expanding the “possibilities of compassion, reclamation of ritual, and queer love as spiritual practice” may seem daunting, but Farahbakhsh assures us that “sonic joyfulness is about getting back into where our ease and safety is, and about how to bring that out in art-based work.”

Adds Ayewa: “It’s a lot of work—and work is work—but at least it’s easy, gentle work.”