Still Listening: New Works in Honour of Pauline Oliveros (1932-2016) is a project initially conceived to mark Oliveros’ eighty-fifth birthday on May 30, 2017. Eighty-five artists were invited to create eighty-five new compositions, each with a duration of eighty-five seconds. Organized by trumpeter Eric Lewis and flutist Ellen Waterman, with help from McGill University students Landon Morrison and Katherine Horgan, the idea was to celebrate Oliveros’ continuing and vibrant presence and monumental influence. A composer, improviser, and musical theorist, Oliveros is perhaps best known for the development of Deep Listening, which she described as “a practice that is intended to heighten and expand consciousness of sound in as many dimensions of awareness and attentional dynamics as humanly possible.”

With Oliveros’ passing in November 2016, the project—which will include an art exhibition, a concert series, and a conference, all held in early June—has increased in significance. All scores will be displayed at an exhibition held at the Marvin Duchow Music Library at McGill, with organizational assistance from head librarian Cynthia Leive. Performances of all eighty-five works will take place during the opening concert of the 2017 Suoni per il Popolo Festival. Many leading Quebec-based musicians and improvisers have already signed on, and some of the composers will perform their own works. A conference on the theme of Improvisation and Listening, which includes academic papers, workshops, and soundwalks mirroring Oliveros’ own practice, will run concurrently.

Musicworks asked Lewis, a philosophy professor and director of the Institute for the Public Life of Arts and Ideas (IPLAI) at McGill, to fill in some details about the conception and works that will be presented. This interview has been edited and condensed.

Musicworks: How did the project come about?

Eric Lewis: I knew Pauline though her participation in a Canadian-based international research project, Improvisation, Community, and Social Practice, which later became the International Institute for Critical Studies in Improvisation, led by Ajay Heble at the University of Guelph. Both Ellen and I have performed with Pauline, and we both thought it would be appropriate and fun to come up with something that recognized her work. In collaboration with her life partner and artistic colleague Ione, we constructed a list of former students and collaborators spanning her history from the San Francisco Tape Center to Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Everyone said yes, and it was obvious that the whole community wanted to celebrate Pauline in this way.

MW: How did the project change when Pauline died?

EL: With Pauline’s passing, Ellen and I felt an added sense of responsibility to get it right. Some composers saw fit to modify their scores upon her death. Originally these compositions were birthday presents to be performed at a party, but now they will be gifted to Pauline’s estate. The secret was well kept, and Ione believes that Pauline never knew right up to the end. It will be both sad and celebratory. We received a fantastic collection of scores, a survey of the breadth and depth of Pauline’s influence. Some are pieces of paper with standard or nonstandard notations, others are sculptural art works that perform their own score. It resembles a survey of postwar compositional methods. Pauline was an advocate for women in the arts, and we hope to capture this important element, in that more than half of the contributions are from women.

MW: What were some of the works included?

EL: We received a score from Roscoe Mitchell titled “Bells for Pauline” for two glockenspiels and four tubular bells; and a piano work called “The Great Beauty (in celebration of the life of Pauline Oliveros),” using standard notation, from Terry Riley, who has not written a traditionally notated score for quite a while.

Olivia Robinson’s “Resonance in Gratitude,” a wall-mounted textile score with LED lights, is intended to inspire thought and vocalizing, one spectator at a time. Similarly, China Blue and Seth Horowitz created “Theta for Pauline,” a 3-D printed object that plays an MP3 file through headphones.

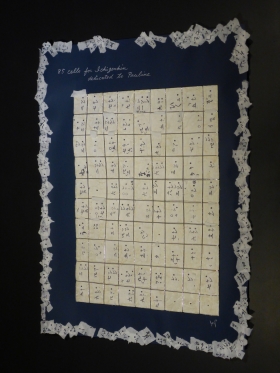

Issui Minegishi’s “85 Cells for Ichigenkin: Dedicated to Pauline” (LEFT IMAGE) is a wire-grid, mixed- media, wall-mounted score. Ichigenkin literally translates as “one-string zither.”

Norman Lowrey contributed “BuddhaBigEars,” a tabletop metal-and-paper sculpture about a foot high, with a six-inch-square footprint. When switched on, it plays the piece through electronic circuitry sounded through a small speaker.

MW: There are some conceptual pieces that are a bit like her Deep Listening exercises.

EL: These performances are internalized, where you view, read, or watch something, and then think about certain pitches or tones or sounds, and perform them in your head. Michael Galbreth gave us “Untitled #6 for Pauline,” a beautiful score written on a piece of parchment which came with a custom-hand-crafted string. The performance is to tie it around a tree, and it ends when the paper is dissolved away. This is very much in keeping with Pauline’s naturalistic impulses, listening to nature and engaging nature as a participant in performance.

And one suspects that Pauline will be somehow present, listening deeply.

FYI: Full programming details are now available for Still Listening: Pauline Oliveros Commemoration, which takes place June 1 to 3, 2017, at various venues in downtown Montreal. Nearly all talks and sessions are free and open to all.

Photo of Pauline Oliveros by Claire Harvie, taken at The Music Gallery's X Avant Festival in Toronto, October 2017.

Lawrence Joseph writes about music in Montreal.