“There’s a group of students who used a term I really liked: countermemory,” Tenzier founder Eric Fillion tells me over Skype from Montreal. “I almost like that better than counterculture.” He’s talking about Tenzier, the avant-garde label which has put out five critically acclaimed vinyl releases in as many years, as well as Tenzier the nonprofit organization. “I don’t want [Tenzier] to be presented only as a label,” he continues. “There’s a mandate that goes beyond putting out records.”

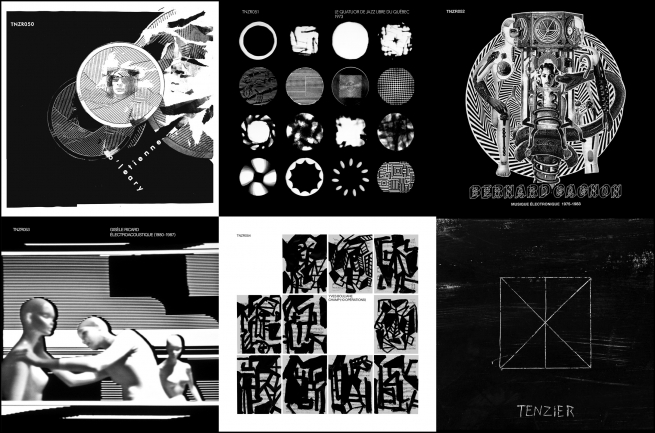

Fillion founded Tenzier in 2010 with the release of Etienne O’Leary’s Musiques de films (1966–1968) [TNZR050]. At a rare screening in Montreal, Fillion had become captivated by the self-composed collage soundtracks that Quebec-born filmmaker O’Leary produced in the ’60s while working in Paris. After matching this music with visual artist Marie-Douce St-Jacques, who created the album’s striking artwork, a label was born. “After one LP, I realized I might as well do another one,” he recalls.

Though Tenzier focuses only on the Quebec avant-garde from the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, it’s decidedly not a home for reissues. Fillion seeks out unpublished, archival recordings by musicians who were “working in the margins,” as he describes them, before cassette culture was born and self-dissemination of music became easier.

Under this umbrella, Tenzier alternates between electronic and improv releases, and already offers a wide range of sounds, from the ruckus of Quebec’s first free-jazz ensemble, Quatuor de jazz libre du Québec [TNZR051], to the electroacoustic hauntings of Gisèle Ricard [TNZR053] or Bernard Gagnon [TNZR052].

While Fillion prefers countermemory to countercultural, his obsession is championing outsider music of forgotten eras. “To me it’s pre-punk, what they were doing in the ’60s and ’70s . . .” Fillion explains. “One of the objectives of the organization is to challenge dominant discourses about Quebec culture. I’m focusing on the people who chose to operate outside the key institutions and universities, against the mainstream—they were real pioneers. They established the networks that my generation, and the one following after me, are building upon. They’re interesting, both because of their pioneering role musically, and for creating infrastructure, in terms of making a point that art and music is a social practice.”

Fillion himself is a retired musician; he stepped back from playing music in 2010 in favour of graduate research on Quebec’s cultural production in the ’60s through ’80s—“but not really avant-garde stuff,” he grins. Tenzier is a way for Fillion to stay in Montreal and Quebec’s avant music scenes and harness his love of history by offering new perspectives on the past, through releases, facilitating artistic collaborations, and special one-off events.

“I want to allow the younger generation to know people were doing what they’re doing twenty, thirty years before,” he says.

Each stylized black-and-white release has had a contemporary Quebec visual artist matched with the music of the past—except 2015’s Champ (10 opérations) [TNZR054] by improv musician Yves Bouliane, who supplied the artwork himself—and live events are curated to bridge different generations of creators.

Support from Canada and overseas has been strong. “People who engage with vinyl are usually very committed to the format and the music,” Fillion says, “I think Tenzier has found a niche.”

As a nonprofit, Tenzier is also committed to securing places for its releases in cultural institutions such as the Quebec National Library and Library and Archives Canada, as well as digitizing archival works. A current project with Éric Normand (Tour de bras) and Mario Gauthier will see a massive digitization of Quatuor de jazz libre du Québec recordings from 1968 to 1974. The undertaking will see hours of music become available online within the next year and a half, alongside interviews and visual components—all this while Fillion plans Tenzier’s 2016 vinyl release (to be determined) and a collaboration with Montreal experimental festival Suoni Per Il Popolo.

Tenzier’s inspiring commitment is not just exposing wonderful, anxious sounds of undergrounds gone by, but tracing new maps for Quebec’s artistic future. “Expand your network, look beyond just your immediate network of friends, and see all the musician-artists who are still there and still have something to contribute,” Fillion advises. “The exchange goes both ways.”