I first met John Oswald as a fellow musician in Toronto’s new music, improv, and modern dance scenes of the 1970s; we co-launched Musicworks in 1978. By his own account, he began mashing up appropriated music on a home tape recorder as a teen. Since then, he’s explored and systematically developed mediated ways to make music of intellectual rigour, humour, musical elegance, and power.

With parallels to sound collage and musical montage, Oswald is best known for the genre of music he coined: plunderphonics. Beneath the surface cleverness, technical adroitness, and structural legerdemain of Oswald’s work lies the theme of the metamorphosis of sound and image, akin to what mid-century French situationists called détournement. Many plunderphonics works feel, to me, like an homage to the appropriated original composition, composer, performance, or performer.

While Oswald’s plunderphonics releases initially landed him in hot water with the commercial record industry, by the 1990s his approach was valued enough that the Grateful Dead came calling. Oswald responded with two critically acclaimed Grayfolded albums. The same decade, the American new music string ensemble Kronos Quartet commissioned Oswald to compose works in a slightly different style. With disarming wit, he dubbed it Rascali Klepitoire, explaining, “These pieces are distinct from my plunderphonics work in that rather than being transformations of pre-existing recognizable recordings of music, which are plunderphonic, rascali klepitoire designates performable compositions or recipes, based on existing scores, often from the classical repertoire or written transcriptions of music.”

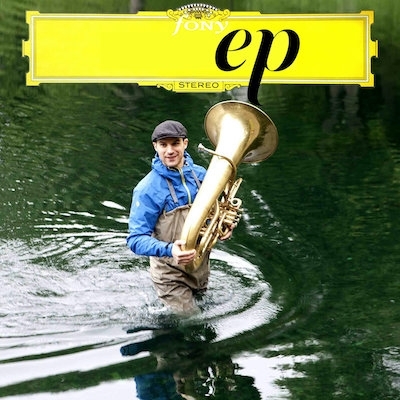

In that vein, Oswald’s imprint Fony has released Classics from the Rascali Klepitoire (teaser) EP on Bandcamp, followed up with three albums giving Beethoven’s music his signature klepitoire treatment.

Classics’ six tracks run the gamut from the hilarious (while always musical) bonus track Ludwig aNew : vol.1 — two 5ths, an unapologetic electronic orchestral riff on Beethoven’s classic symphony, to the thoughtful Oswald–James Rolfe co-composition bird, for chamber orchestra and soprano. The latter is a radical, playful cabaret-esque transformation of Leonard Cohen’s “Bird on the Wire,” though it strongly hints at many more musical and lyrical layers.

In from exquisite lune, which is based on Debussy’s familiar piano piece Clair de lune, the mood shifts dramatically to soft, reflective, and slowly unfolding. Oswald subcontracted the score from Toronto composer Linda Caitlin Smith. The music, reflecting Oswald’s pervasively palimpsestic methods, is rendered by two different Disklavier pianos, recorded separately and mixed in Oswald’s studio into an ensemble version.

Continuing in the same vein is lontanofaune, my favourite track on the album. Credited in the liner notes to “Claude Debussy and György Ligeti, superimposed and mixed by John Oswald,” the work’s rich orchestral sound and hazy harmonic textures—especially in Ligeti’s 1967 Lontano, but a feature of both source works—are relieved by recognizable melodic themes from Debussy’s 1894 symphonic poem Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun. I find lontanofaune moving and the entire album musically deeply satisfying.