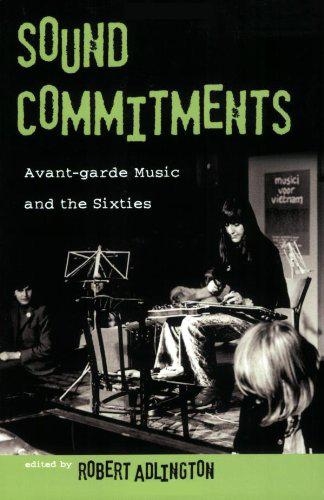

“If you remember the ’60s, it means you weren’t there” is a cliché with a kernel of truth in it—especially the insistence that rock sounds then subsumed other music. Yet the ’60s also saw mass acceptance of new and electronic music, while jazz’s most radical sounds divorced it from its role as entertainment.

Sound Commitments aims to redefine that momentous decade in a dozen essays about the advanced sonic experimentation that attempted to negotiate the currents between political movements and individual expression. On the evidence, triumph of the latter over the former created the longest-lasting sounds.

Some essays are more insightful than others. Most notable are Benjamin Piekut’s piece on leftist composer Henry Flynt, Amy Beal’s history of the pioneering improvising electronic group Musica Elettronica Viva (MEV), Yayoi Everett’s take on Japanese avant-garde music, and Peter Schmeltz’s tale of one Moscow studio that was a centre of pre-Glasnost sonic adventures.

Others of these essays may be of only specialist interest. Beate Kutsche’s elaboration of the socio-political debate involving Süddeutscher Runfunk’s music producer’s refusal to première Nikolaus Huber’s Harakiri after it was commissioned, retells a brouhaha in a beer stein. Similarly Sumanth Gopinath’s parsing of Steve Reich’s 1966 tape-loop piece, Come Out, which the composer says is open to many interpretations, attempts to politicize by inference. It is, for example, far-fetched to insist that Reich’s tape manipulation is “doing violence” to the source and is comparable to the police violence done to the subject whose voice was originally recorded.

Somewhere in the middle between insightful and specialist is Bernard Gendron’s examination of how the 1964 October Revolution concerts and formation of the Jazz Composers Guild, led to acceptance of so-called second-wave avant-garde jazz musicians. Crucially, the one essay dealing exclusively with jazz examines economic necessities and artistic exploitation rather than the art-music grants system at a time when “the artificial borders between classical and jazz experimentalism were still being strongly policed by high culture.” Unfortunately Gendron’s evidence for the canonization of the second wave, based on specialist magazine coverage, is somewhat spurious, considering that he eventually writes, “economics trump[ed] aesthetics,” as rock music gained massive popularity.

Subverting so-called popular sounds to fit composed music is a theme throughout the book. A member of the hard-line Workers World Party, Flynt extended his criticism of “European white ruling class art” not only by demonstrating against a Karlheinz Stockhausen concert, but also by insisting that “Negro vernacular music” must be the only sounds for Marxist-Leninists. He also attempted to translate Ornette Coleman’s innovations to violin when recording agit-prop songs with his rock–blues band.

Similarly, the members of Rome-based MEV, an improvising group consisting of composers, operated as a “tribe” that “believed we could transform the world,” recalls Alvin Curran. Other notable MEV-ers were Frederic Rzewski, Richard Teitlelbaum, and Steve Lacy. Utilizing a portable synthesizer, MEV staged loft performances with audience participation and illegal outdoor shows using radios and contact microphones. Encouraged by the climate for new music in Italy—and supported by American Foundation funding—that version of MEV splintered, following conflicts between those with conservatory background and those who were self-taught.

Elsewhere, performances given at Tokyo’s privately funded Sôgetsu Centre evolved from those involving a blend of traditional Japanese and advanced music—including a John Cage showcase—to happenings such as Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece, which deals with voyeurism and violence. “Themes of social alienation and individual autonomy . . . attempt [ed] to transcend the norms and hierarchies of traditional Japanese society,” notes Everett.

Analogous but unique, the concert series utilizing the ANS synthesizer at Moscow’s Scriabin Museum— named for composer Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin—functioned in the Vnye border in and outside of officialdom because of inventor Yevgeniy Murzin’s high-level party contacts. Although the technology-loving Soviets couldn’t afford to mass produce the ANS, the existing one “officially disappeared” into the museum. Thus, experimental music involving trance, jazz, dance, improv, happenings, costumes, and puppets flourished at the Scriabin. Murzin’s 1970 death meant that rock bands such as Boomerang literally took centre stage. Although the museum’s experiments meant that jazz and rock were judged by the same criteria as so-called “academic, intellectual” music, the Scriabin was “dissolved” in 1975 and the ANS transferred to Moscow State University.

Recounting little-known tales like these confirms Sound Commitments value in tracing avant-garde sound’s movement from the academy to the streets. More volumes of like quality about those times would be welcome.