As spring erupts in the Centre-du-Québec region, so too does FIMAV, the festival of exploratory music that’s been running since 1984. “Eclectic” barely describes the four-day event. Its scope ranges from near-silent to deafening, from the ineffable to the ridiculous. The music originates in Montreal or Tokyo and points in between, taking in every methodology from through-composition to free improvisation. As one traverses a day’s concerts and venues, a map of the festival—and the genres it presents—emerges: an uncanny mix of musics that no one listener could love—even like—yet that has seen this festival thrive. Among the achievements of this year’s festival were the high proportion of women musicians on stage and the range of Asian musicians and music presented.

Some of that range was apparent on opening night, when the first concert in the Carré 150 concert hall paid tribute to Québécois composer Walter Boudreau, a founder of the elastic musique-actuelle concept, with two different ensembles: the first, the young 333 ToutArtBel, played Paix, from 1972, a tensely conducted work that jumped genres in a way that perhaps inevitably felt dated; the second, performed by the august Société de musique contemporaine du Québec and conducted by Boudreau himself, was very different: Solaris (Incantations VIII-IXh) is a mature work reminiscent of Pierre Boulez. A now rare foray for FIMAV into contemporary composed chamber music, it was a richly orchestrated piece with subtle textures developed between strings, winds, and percussion.

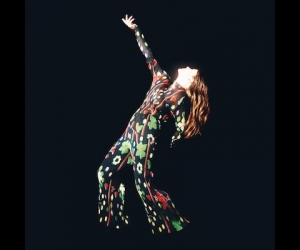

Down the street at the Colisée—a space usually reserved for sports, from hockey to motocross—the composer, singer, and erhu master Lan Tung demonstrated levels of methodological interactivity unthinkable just a decade ago. Her Giant Project combined two ensembles, her Vancouver-based Proliferasian, comprising jazz and Western classical musicians, and the Taiwanese Little Giant Chinese Chamber Orchestra, a traditional group playing such instruments as sheng, pipa, and zheng. The program included composed pieces that cleverly explored cultural contrasts, including an opening piece that matched Ron Samworth’s manic electric guitar with the almost cinematic merger of Eastern and Western idioms. Collective improvisations among selected members of the two ensembles developed a startling synthesis of methods, creating new sonic colours among the mingled instruments.

That improvised synthesis of East and West arose on Friday as well, when pipa player Liu Feng joined violinist Malcolm Goldstein and guitarist and mbira-player Rainer Wiens. Wiens created delicate backdrops against which the others drew sparkling lines. Goldstein improvised distinctively Chinese lines through melodic shape and rhythmic emphases, while Feng explored the sheer sonic power of her resonant, guitar-like instrument. While this trio forged its identity in interweaving lines, another did it through dramatic differences. Toshimaru Nakamura has been combining his no-input mixing board with Martin Taxt’s microtonal tuba since 2006, creating stark mixes of electronics and sustained bass tones. Here they added Danish saxophonist Mette Rasmussen, a wildly exploratory player from the world of free jazz. Given the differences in their three instruments, it’s hard to imagine close interaction, but the results were just as arresting when they seemed to pursue independent paths as in moments of close congruence, the three developing a sound world of sufficient space to accommodate their independent voices—calm, chaotic, industrial, abstract—as fascinating simultaneities.

Last year FIMAV launched an afternoon acoustic series at the Église Saint-Christophe-d’Arthabaska, a restored nineteenth century church with a resonant, light-filled interior. This year it was home to a brilliant series of solo performances, each a festival highlight. The first was by Swiss vocalist and violist Charlotte Hug, whose performance was shamanic, a wild calling-up of spirits and sounds with Hug exploring the limits of voice, from near-whistles to gravelly, bass multiphonics. At one point she matched high-speed glissandi between voice and viola; at another she reduced the performance to the near-silence of bow-hair dragged across viola body. Every gesture made sense and yet was a complete surprise.

The following afternoon, piper Erwan Keravec somehow matched that achievement with a display of technical innovation, articulation, and sheer mastery that would put him in the front ranks of solo improvisers. Within the pipes’ legendary roar, Keravec found abundant opportunity for grace, complexity, and subtlety, exploring polyphonic possibilities as well as the instrument’s traditions. The third of these solo concerts was by Lori Friedman, who brought soprano, bass, and contrabass clarinets to a program that mingled improvisations and compositions, presenting them in ways that somehow lent complex scores the feeling of spontaneity and improvisations the structural clarity of written works. Friedman’s performance balanced whimsy, virtuoso complexity, and a deeply felt lyricism, a singing quality that illumined the reflective, melodic passages that arose during the hour-long set.

Friday night was devoted to jazz of a particularly heady sort, with two great bands touching on traditions in deeply rooted programs. ROVA, the San Francisco-based saxophone quartet, emphasized works in which soloists improvised against composed ensembles, the format suggesting a radical update of the Basie and Ellington bands, bringing an element of swing to an otherwise contemporary language. William Parker’s In Order to Survive possesses all the vitality and necessity the name implies. The bassist began with a forceful ascending bass line, anchoring a performance in which the brilliance of senior pianist Dave Burrell, drummer Hamid Drake, and saxophonist Rob Brown fused to create driving, transcendent music.

Other concerts of note included the Vancouver-based Dálava playing Moravian folksongs transcribed a century ago by singer Julia Ulehla’s great-grandfather. Saxophonist Mats Gustafsson provided all the volume anyone could want, both with his thunderous group Fire! and in a trio with noise artist Merzbow and drummer Balázs Pándi.

And, oh yes, the ridiculous: singer YoshimiO (of Boredoms fame) shrieked over electric sitar and percussion in a bizarre appropriation of Indian classical music called Saicobab; it seemed reasonable, however, in comparison to the Russian group Phurpa, which consisted of three men in robes and hoods seated cross-legged onstage, burning incense and performing a heavily amplified travesty of Tibetan ceremonial music. It evidently appealed to more people than the solo series at the Église, suggesting that it somehow made possible the musical wonders and unique balance of FIMAV.

Photo: Erhu master Lan Tung (far right in red, seated) and her Giant Project perform at FIMAV 2018. Photo by: Martin Morissette