Rebecca Bruton describes her work as an “understated, Surrealist folk music”—music that’s experimental but also simple, with a sensuousness and a weirdness to it. “Music that makes sense,” she says, “but you’re not sure why.”

A composer, violinist, and vocalist, based in Calgary, Bruton studied music first at York University and then at Simon Fraser University, where she graduated with a master’s in composition in 2016. Since then, she’s already worked with some of Canada’s leading new-music ensembles: with Continuum Contemporary Music through the Canadian League of Composer’s composer mentorship program PIVOT in early 2017; Quatuor Bozzini’s Composer’s Kitchen 2017; and most recently, the award-winning Quasar saxophone quartet’s New Chapter program, supported by the Canada Council for the Arts. Bruton was one of eight Canadian composers selected to participate in a five-day workshop with Quasar in Fall 2017, before their eight new works receive their premiere performances by the quartet in May 2018.

While attending the Composer’s Kitchen, Bruton had started to think about tarot cards: how each card in a deck means something unique, but how those same cards could also be shuffled and combined. The result was her 2017 string quartet All I dreamt; twice as much.—where the central movement is a “deck” of rearrangeable score fragments.

When we spoke in early October, Bruton was about to meet the Quasar quartet at Vancouver’s Western Front artist-run centre for the workshop portion of New Chapter. She had some concrete ideas about the sonic direction her piece would take (“multiphonics, saxophone glissandi, and different forms of long tones”), but the possibilities were open—and so, as a place to start, she returned to the tiny cards of music she made for the Bozzinis.

The following interview has been condensed and edited.

Musicworks: Where are you with this piece right now?

Rebecca Bruton: I’m workshopping sketches [in a few days], so right now I have a lot of ideas floating around. It’s like I’m following a trail and I’m trying to grasp something, but it’s still somewhat ungraspable. But I’m trusting that there’s something there, and that sooner or later it’s going to make sense.

MW: What form are those sketches taking?

RB: I started with the idea of tarot cards: how each card is a really potent world unto itself, but then means something different in relation to the cards beside it. So I’ve been working with these graphic scores on little cards, with very distilled sonic ideas. It’s almost a collective generation, where I arrive to the group with a bunch of really small things, but the possibilities end up being quite broad.

The other thing that I’m working with is a book by Karin Bolender called R.A.W. Assmilk Soap. It’s a story about a woman who engages in a ceremonial marriage to a donkey, with the goal of exploring interspecies relationships through silence. The idea is that she’s coming to know the unknowable—another species—through this silent companionship. She’s interested in how language creates intimacy but also obstructs it.

MW: How does that idea of intimacy-through-silence translate to a saxophone quartet?

RB: That’s the question! I’ll likely be using a lot of metaphors taken from the book. But I [also] think of music as touch, and that’s why it’s about intimacy for me—because it’s vibrating our eardrums, and it creates a sense of physical connection between players and listeners.

A theme in a lot of my work is the difference between a piece of music representing something and it actually being something. When I think about intimacy, a really sentimental song can be a representation of that feeling. But then I’ve found that working with line drawings rather than a score, for example, causes the players to listen to each other in a much more intimate way. I like the feeling that gets produced by, say, a really sentimental country song, but I like the process that happens in these more abstracted techniques.

MW: Will the cards and graphic notation still be a part of the final score?

RB: I’ve been really interested in ways that you can pair them [with standard notation]—and also in moving out more into the extramusical. Could I include a graphic score on one card, and then another card that is a thirty-second film—or a picture, or a set of words—[after which] the piece goes back to being a score again?

That idea came from when I was in the Czech Republic this past summer and saw Jennifer Walshe speak. She goes beyond just sound and includes, say, two people dancing and staring into each other’s eyes [as part of a piece]. She says that it’s “music that lets the world in.” So I’ve been interested in ways that my material could “come in”—moving beyond representing extramusical material and directly engaging with it.

The work discussed in this article, Mammalian Mother Tongues, will be performed by Quasar quatuor de saxophones on May 30 in Montreal at le Gesù (8 p.m.).

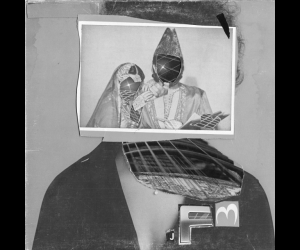

Photo of Rebecca Bruton by Benjy Wilson.