I sit staring at the laptop screen in my Beijing hotel room. Writers’ block. Silently trying to formulate words. No sounds enter my consciousness. Only the insistent hum of the laptop. Until my listening body is dropped into a pool of sound. Concentric sonic circles ripple out from the imitation Qing chair. My energy is dispersed via a wave of sudden awareness, not of what is on the screen in front of me but of what is surrounding me, thriving, washing in on me from all sides, swelling out in ever-expanding sound rings from where I sit on my chair within the first ring road of the city.

2010 inner ring (sound ring 1)

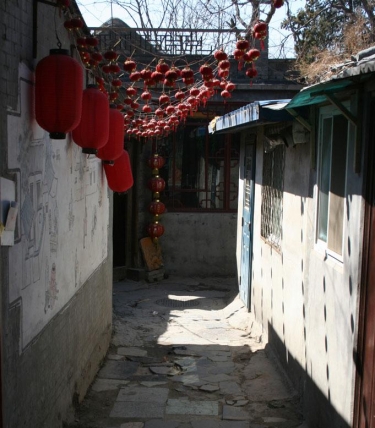

daytime—the high-pitched voices of children playing tag, squealing; women gossiping and scolding—xiao-er xing!—teasing their children; men and women hawking wares and services (I’m just off the main commercial drag of the mostly gentrified hutong, so can’t hear the tourists)

evening into night—man on mobile speaking insistently, young couples murmuring, laughing, troops of young men caterwauling, languorous sweeping with bristly brooms, metal shop-doors being pulled down with satisfaction, clicking of high heels on stone pavers, scraping metal of shovels against hard dirt of late-night construction crew tearing down yet another hutong dwelling

Writing a ghost story while alone in Beijing is something I both relish and dread. The sounds, even when spiked and hyper, of life in the hutong (ancient narrow lane or alley) outside my hotel windows are a comfort—contact with reality, the present, the living. But even as I listen, soothed, the hutong is being scraped and clawed apart from all around me, as daily demolition and capital development grind their steady way.

Beijing’s urban plan is aligned in its organizational structure with something similar to the Cartesian rationalism that governs Western cities like Toronto and New York. Overlaid onto Beijing’s vast grid design are a series of ring roads, seemingly organized according to the Concentric Circle Theory, also known as the Burgess Model, one of the earliest theoretical models to explain urban social structure, where concentric circles of land use develop around a city’s centre, the ring of power.

The old gateways, now mostly gone, were the bustling eastern entry to the Silk Road, and part of the early city walls that enclosed the metropolis and constituted the first ringing of the city. Beijing’s first ring road, no longer so named, ripples out from the Forbidden City and Tiananmen Square to the second ring road that ripples out to the third ring that ripples out to the fourth that ripples out to the fifth ripples out to the sixth ripples out southeasterly to the alluvial expanse of the North China Plain and northwesterly to the encircling mountainous terrain of Xishan and Yanshan.

June 4, 2010 intermediate ring (sound ring 2)

muddled muffled musical porridge of many hi-fis playing varying versions of Mandopop (blandly sentimental Mandarin pop), traditional Mongolian singing in the afternoon, pop at night, and the pipe-playing panhandling family that frequents the commercial drag of the hutong and that stirs both pathos and aversion in me

Aggressively pushing at the power ring edge is the new social order, a younger generation of citizens caught between quickly fading traditions and the new world order of digital technology, information highway, social media, global tourism. Even with the trend of re-embracing Confucianism, Buddhism, tea ceremonies, and the like, there is a breach between the deeply learned and integrated habits of older generations—e.g., that of my mother—and the adaptations and appropriations of the Mao and post-Mao generations. For those more modern generations, tradition is a trend, and the ring of power is not daunting.

I first visited China in 1983 as a young, wet-behind-the-ears idealist convinced that I would locate my true identity in the motherland. It turned into a jolting, humbling experience where the yawning gap between my fantasies about China and the reality of China undermined all my ingenuous presumptions. I spent most of the three months of my stay in Beijing mingling—bicycling, jamming myself into city buses, attempting to blend in by shedding earrings and donning my cousin’s rural re-education clothes. Beijing was a flat grey expanse of a sameness that was dictated by the pervasive paranoia held over from the Cultural Revolution years.

It would be over twenty years before I was to return. By 2004, it didn’t matter what time of the day or night it was—I could look out the window at 3:30 in the morning and see the cool blue sparks of welding frenzy all over the urban landscape. It seemed like half the city was constantly being torn down and thrown back up. And as I listen from my latest residence in the hutong near the Gulou (Drum Tower), an adjacent building is steadily torn down, diminished daily. Many neighbourhoods are happenstance in Beijing. All is thriving and lively one moment, but can shift, relocate, disappear, within a year. In this kind of climate, nothing can be relied on and all citizens must remain alert, itinerant-ready.

Floating thoughts while I'm procrastinating getting to my work

There's a surprising amount of pessimism on the part of some Chinese about their future, contrary to the recent hype in Western media regarding the country’s impending superpower status. I'm beginning to get a handle on the Chinese psyche, despite the squeaky-clean, over-the-brim optimism propelled by the Chinese media, and the battle charge for the acquisition of luxury items, in a darkness befitting the vale of tears. Maybe it's a way of warding off the inevitable, what many Chinese realize: that it's not possible to sustain all this, to find ultimate balance.

Venturing out from the relative comfort zone of the first two sound rings, we reach the ring of traffic that both chokes and transports the inhabitants of this zone. Ring roads are a favoured route of Beijing taxi drivers. They are swung further out, but they get to their destination faster.

June 4, 2010 outer ring (sound ring 3)

honk honk honk honk honk honk honk honk honk honk honk honk honk honk honk, white-noise thrummm of relentless traffic, squeaking of bad brakes, occasional gong, gong, gong-gong-gong, dulled with atmospheric ring distance, of someone beating the massive drums in the Drum Tower (I can see it from my window)

What does development in Beijing sound like? It’s not the mechanistic clunking and churning of mighty machines tearing down old hutongs, but the persistent manual brick-by-brick work of migrant labourers; it is the layered sounds of neighbourhoods in transition, of the ancient, eternal sounds of family dynamics at work and human relationships in process. The sound rings I hear originate in the intimate unhurried core of social life, urban or rural, as it exists in all human societies.

As the sound rings expand beyond the power centre of the principal metropolis in one of the most rapidly developing nations on the planet, how does it resonate to the small villages and agricultural belts outside of the capital, outside the rings of influence? Does the sound become warped with distance and interference? Does it dissipate to barely a sigh?

Everything and nothing has changed in the city of commerce and machinations. Goods and political measures roll in and roll out. The headlong rush to build and accumulate stem from the fear that this pace is not tenable, that this won’t be possible in a generation or two—the raw materials just won’t be there. Nothing more will roll into the city, nothing roll out. Will the city be silent?

Image: ©CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 2009 Murdocke23.