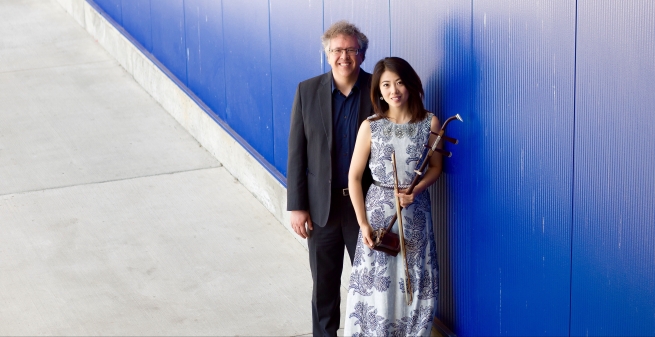

“Let’s begin with a short history of this instrument,” says Nicole Ge Li, in a video shot at the Vancouver offices of the Canadian Music Centre. She’s speaking to a roomful of composers, gathered there to learn more about writing for PEP (Piano and Erhu Project), her joint undertaking with the man who’s just introduced her, Corey Hamm. PEP’s online audience has grown exponentially since the duo’s debut in 2012.

“The erhu is one of the most important string instruments in traditional Chinese music,” Li continues. “It’s made up of two strings and a bow. We think the erhu functions like the Western violin, so it has been called the Chinese fiddle in many countries. The word erhu is actually made up of two distinct Chinese characters. The first character, er—or two, in English—can either refer to the two strings of the instrument or to the fact that it is the second instrument in pitch and character in the erhu family of instruments. The second character, hu, is a reference to the Hu people, who first introduced this instrument to China, over one thousand years ago.”

The Zhengzhou-born performer goes on in the video to explain that despite its long history in folk music, the erhu has been a subject of serious study only for about a century. She talks about its construction, its tuning, its three-octave range, and its fingering, illustrating her points with short musical examples.

“In addition, the erhu is still evolving,” she says later in the six-part series, which can be viewed online at PEP’s Web site. And while she’s talking specifically about recent additions to the erhu family—such as the shao quin, pitched a fifth lower than its smaller cousin—she could very well be talking about the new expressive possibilities being discovered for the erhu and its kin by composers all over the world. And that’s largely the result of the work that she herself has been doing with Hamm for the past five years. As PEP, they’ve embarked on an extraordinary intercontinental and intercultural venture: introducing the erhu to Western new-music composers and audiences, while opening up new sonic possibilities for the instrument in its native land.

Like so many other brilliant ideas, PEP began almost accidentally, when Li and Hamm’s separate bands shared a stage in a program that included new works by respected Canadian composers Owen Underhill, Dorothy Chang, and John Oliver.

“Nicole is the concertmaster of the British Columbia Chinese Music Ensemble, and I’m in the Nu:BC Collective with [flutist] Paolo Bortolussi and [cellist] Eric Wilson, and we had this joint performance,” Hamm recalls, in a conference call with Li. “That was a really fun thing.”

Fun, and gratifying enough that Li asked Hamm to play piano at her own solo recital a few weeks later. “We loved it, loved working together. So we thought, Okay, this is fun; we get along well musically and otherwise, so let’s explore more erhu-and-piano music!

“Nicole brought two or three different volumes of Chinese music that had been written for erhu and piano,” Hamm continues, “and we played through a bunch of it. It was all very nice music, but it tended to be one style: it wasn’t really progressive, and really none of it was exploring the possibilities that exist for contemporary music as we think of it. So we thought, Oh, well, there’s a little niche; maybe we can explore that. Why don’t we ask some of our composer friends?”

An informal call-out to some twenty composers, most of them Vancouver-based, garnered an almost unanimously positive response, even though Li and Hamm had no commissioning money to offer. They did, however, provide their friends with the perfect mix of a blank slate and some known quantities: two recognized virtuosos, and a combination that no one had written for before.

“We wanted to have as many different styles as we could,” Hamm notes. “We really wanted to have popular things, and movie-music things, and crazy avant-garde things, and everything in between: with electronics, without electronics, whatever—just composers that we really liked. And almost everybody said yes.”

For Dorothy Chang, writing for PEP was a natural development—after all, one of her pieces was on the program of the concert where Li and Hamm first met. Although piano is Chang’s first instrument, the Chicago-born, Vancouver-based composer had studied erhu while living in China.

“I’d written for Chinese instruments before; I have several pieces for mixed Chinese and Western ensemble, mostly for slightly larger ensembles,” she explains, in a separate telephone conversation. “In those, I had played a lot with the idea of cross-cultural [music], mixing East and West. So when Corey and Nicole approached me to write a piece for them, I decided I didn’t want to do that again. And one of the things that I find most amazing about the erhu is its ability to take on other styles and the repertoire of other instruments. So I thought I would write a set of pieces where not just erhu, but erhu and piano, could take on different personalities. One of them is a tango, and one is more like a folk song . . . It’s a set of four whimsical pieces, and I decided I’d just have fun with it.”

Chang’s Four Short Poems is among the highlights of PEP’s second CD, issued on Vancouver’s Redshift label. At least three more volumes are in the works. Also underway is a double concerto for erhu and piano, which Chang is writing for Li and Hamm to perform with the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra in 2018.

“They requested specifically that it be a showcase piece, and something that would explore the cross-cultural aspect of the duo, but beyond that, it’s up to me,” she notes. “As far as I know, there’s no existing double concerto for erhu and piano, so I’m going to have to do my homework!

“I’m going to think about that aspect of hybrid cultural identity and how that might play out in the music,” adds Chang, who spent part of her youth in Taiwan. “I might go very far into the idea of folk song . . . maybe collect folksongs from both cultures and somehow create a new type of mashup. That’s something really exciting to explore.”

Just as exciting for Chang, though, is the idea that her music is getting much wider exposure, thanks to PEP’s promotional efforts. Hamm and Li are not just recording the pieces submitted to them: they’re touring worldwide, making professional performance videos and posting them on YouTube and the PEP Web site, and planning to issue the complete scores for each CD release. And there’s more.

“Nicole is involved with this online music-education program,” Chang notes. “It’s a huge online school thats being developed somewhere in China, and part of it is that the performers teach how to perform specific repertoire. So she’s interested in taking some of the repertoire written for PEP and putting it out through the school, reaching who knows how many people . . . literally millions!

“Nicole and Corey are just so dedicated to what they do and to the music that’s written for them,” she adds. “They’re so creative and inventive in getting the music out there and creating opportunities for the music, for the composers, and for themselves. I think that’s why so many composers are enthusiastic about the project.”

In addition to developing online tutorials for the iArt School, Li and Hamm have already had some success bringing new repertoire for erhu and piano into China, where they have performed. The works that have been created for PEP appear to fit a growing need for chamber music that goes beyond the old-school erhu-with-chords format, and some—Vancouver composer Roydon Tse’s Blues n’ Grooves in particular—are quickly becoming part of the established repertoire.

“Two or three years ago, a world-class erhu player [Song Fei] from the China Conservatory of Music brought her ensemble to Vancouver to do a visit and performance with UBC, at the Chan Centre,” Li says during the conference call with Hamm. “We introduced PEP to her, and also performed Roydon’s piece. She was very impressed, and she spent some time looking at scores. So Song Fei was the one who brought this piece to China, and it got performed multiple times.

“On our tour of China we went to her institute in Beijing, and finally we got a chance to play a whole concert to her and her school,” she adds. “And after that, she and another teacher there asked for more scores. So they’ve been playing several of PEP’s scores already, especially in chamber-music concerts, because there is a lack of chamber music for erhu in China.”

As a Chinese-trained musician living in North America, Li has been particularly gratified by how playing contemporary music has sharpened her technique. Having been privy to this from the start, Hamm observes that his musical partner is “maybe the only erhu player who has really mastered this type of stuff.

“There are a lot of fantastic erhu players, but not with this vast amount of experience in contemporary music,” he says. “Now, I can’t say that for myself at all: there are millions of fantastic pianists, and I’m just one of many. But Nicole is not . . . I don’t think that there is another erhu player with this kind of ability in contemporary music—but of course we hope that that soon changes, because the reason for PEP is to get work like this out there and get other people playing it. We don’t want to hog all this for ourselves.”

“Some other players and conductors, they tell me I pick up quite fast,” Li says. “I think that’s all because I play so many PEP pieces. And then certainly, tempo-wise, Chinese pieces are always like 4/4, and never really changing in the middle of the piece, but contemporary pieces, they change all the time, and there are a lot of weird rests. Also I really have to keep my ear on Corey all the time, and that’s made me more sensitive to music. When I go back to some Chinese pieces, I feel, strangely enough, that their structure is more clear than before.”

“I think she has shown tremendous growth,” says Chang. “She pretty much can play anything, as far as I can tell. I did sense, at the beginning, that some things were new for her . . . and now it’s flawless.”

That’s an opinion shared by Jared Miller, whose Captive appears on the duo’s debut CD. “She’s incredible,” he reports, on the line from New York City. “I mean, the piece that I wrote for them is not easy—for the erhu in particular—and she just nails it, which really says something about her versatility and mastery of the instrument.”

Li will soon have new challenges to face: at the time of our interview, she had just announced that she was pregnant with her first child. But her work with Hamm continues. Not only has the duo’s repertoire expanded from the original twenty pieces to approximately sixty, there are at least another thirty in the works, with the composers ranging from internationally recognized masters Frederic Rzewski and Michael Finnissy to rising stars Gabriel Dharmoo and Remy Siu and acclaimed Chinese artists such as Gao Ping.

It’s a heartening development, especially—as Hamm notes—at this time of rising nationalism in the political sphere. “We’ve encountered no xenophobia; instead, there’s been an embracing of it all,” the pianist notes. “So in spite of what’s going on down south in the States—and elsewhere, too: even in our own country, Canada—there seems to be a real interest and enthusiasm, at least in the arts, for cross-cultural pollination, and we’re excited to be a part of that.”

Top photo of Corey Hamm and Nicole Ge Li of PEP by Oby Ivan Su. Performance photo of PEP by Robin Wan.