In many respects, the year 2020 was a time of reckoning for Asian Americans. Hot on the heels of the landmark Asian ensemble-cast blockbuster Crazy Rich Asians, South Korean filmmaker Bong Joon-ho made history with Parasite, which took home the first Academy Award for Best Picture ever to be received by a subtitled film. After a decades-long struggle for representation and legitimization from Hollywood, Asian Americans shared this brief moment of pride. Just a few weeks later, however, shutdowns in cities across North America due to the COVID-19 pandemic triggered waves of anti-Asian sentiment across the continent. Hate crimes against Asians surged in both Canada and the United States through 2020 and into 2021. Yet despite these frequent large and small incidents of racist violence, the Asian American community was, at the same time, galvanized by the unprecedented political unity around the #StopAsianHate marches.

Marginalized communities across North America seek belonging in the context of media representation. For many, it is a valuable symbol of a widening definition of the identities that make up Western popular culture. However, in the wake of escalating attacks on the Asian American community, the urgent insistence on media representation lost its lustre; a true sense of belonging is rooted in the absence of fear and violence. Rather than fight for legitimization in the eyes of North America’s media gatekeepers, many artists across the continent have been focusing their energy on the creation of alternative spaces in which to centre themselves, as well as on preserving the existing artifacts of their cultural and heritage.

In Canada, Chinatowns across the country face predatory real-estate development that often results in the kind of gentrification that displaces the most vulnerable segments of marginalized communities. Saskatoon-based respectfulchild and Montreal-based Parker Mah—both Canadian musicians of Chinese descent—are reclaiming their own identities and also advocating for the preservation of Chinatowns through their art practices. In doing so they create radical new self-defined models of what it means to be Chinese Canadian.

“I love the idea of a gate as both an entrance and a portal, as if you’re going from one place to another. The image of the gate was transporting us, connecting us from our physical, mortal world to the spiritual, ancestral world.”

— respectfulchild

In October 2020, musician and sound artist respectfulchild suspended a delicate, sculptural framework from the ceiling near the tall windows in a corner of Remai Modern, a new museum of modern art in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. As part of this installation piece, entitled 落叶归根:: Falling Leaves Return to their Roots, respectfulchild invited people to write messages to their ancestors and submit them on paper or online (to be printed out) and gradually papered the gate frame with notes. In December, respectfulchild “handed over” the messages to the ancestors in a ceremony, burning the paper, and letting the smoke carry the words to the heavens.

A Malaysian-Chinese settler Canadian and an agender nonbinary artist, respectfulchild is known primarily for meditative and sensual ambient-music compositions that combine violin and electronics, and their practice has broadened to include sound design and sculpture: “respectfulchild has kind of morphed into a space where I can explore anything.” While preparing a fall 2020 exhibition at the Remai Modern, respectfulchild learned that the land the gallery sits on had been the location of Saskatoon’s Chinatown in the early twentieth century. While many people familiar with their work expected them to create a sound installation, respectfulchild instead chose to build a gate as a homage to the early Chinese settlers and Indigenous ancestors, a sculpture that was meant to be burned in the spirit of Chinese ancestral-worship practices. In exploring and honouring ancestry and tradition, the piece symbolized Saskatoon’s proposed Riversdale Chinatown Gate, which was never built, as well as the ephemerality of Chinese Canadian identity—a theme that has come to permeate respectfulchild’s work.

Their artist name is a riff on their Mandarin name 敬兒 [jìng er]: “It’s kind of funny that I use the English version. To me it feels so obviously like this translated name, and it feels kind of janky. That’s kind of how I feel living between multiple cultures and multiple worlds—like a janky translation of cultures, in a sense.” In their early twenties, respectfulchild describes grappling with their sense of social responsibility while navigating the worlds of community organizing and activism. “I was throwing myself into so many different roles and slightly failing at them. I was trying, but not really doing that well. Eventually I realized that maybe that’s not the role for me, but that’s okay. I can still care about stuff, and I don’t have to try to be something I’m not.” In response, they made space for themselves in the world of respectfulchild to explore questions of connection to self and of meaning in their identity. As their practice expands to include more disciplines, so too does respectfulchild’s willingness to embrace themself and the complexities of their experience.

“Sometimes I feel like I’m being too nice, like I’m being too respectful,” they say, describing the role of activism in their art. “Some people can be really abrasive or challenging, but when I try to do that it still comes off in this gentle and embracing kind of way. That’s part of the Asian American identity: when you’re seen as the respectable group, the message is easier to digest because it’s said in a nice way. I’m trying to challenge myself to not fall into that, but also to accept that maybe that’s just the way I am.”

Their 2017 album 在找 :: searching :: delicately embodies these tensions with its enchanting layers of violin loops and swirling ambient rumbles. Moving between serene meditations and tense evocations of anxiety, the seven compositions embody respectfulchild’s at times wistful and other times joyful journey to connect with their ancestry. “Learning about Saskatoon’s first Chinatown and Chinese history in the prairies had me thinking about connections between past and present. These patterns of racism persist even if they look slightly different now.”

“For instance, at one time Chinese people were forced to open laundries. They were doing the work that white people didn’t want to do, they were being paid terribly, and at the same time there was the rumour that they were stealing white people’s jobs. It feels familiar when compared to the narrative of migrant workers on farms today. It becomes one more reason to stand in solidarity with each other. Our communities are experiencing the same attitudes. It’s being repackaged again and again.”

For many Asian American musicians, racial identity becomes an awkward patchwork of distant nations and ethnic groups that occupies the space between Black and white. Montreal-based musician, DJ, and cultural educator Parker Mah bounced between those polarities as a pianist, moving from classical music to jazz before finding his voice writing original compositions that are a rich hybrid of musical influences.

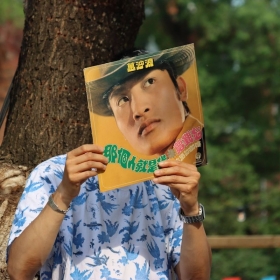

Mah’s artistic practice is closely connected to his efforts as a community organizer in the city. As founding member of the Chinatown Working Group and the Progressive Chinese Quebeckers, he’s had palpable impact as an activist, although his involvement largely arises from making art and staying engaged. “Community organizing has come to me not as something I chose, but from wanting things to change and to see things with a critical eye,” he says. Progressive Chinese Quebeckers was founded after the release of directors Malcolm Guy and William Ging Wee Dere’s 2013 documentary Being Chinese in Quebec: A Road Movie, in which Mah and a companion travel the province to meet other Chinese Quebeckers. The film (which includes music from Montreal-based Chinese Canadian DJ and producer Kid Koala, aka Eric San) inspired a swath of artists, activists, and academics of Asian origin to seek out community; the group they created advocates for Chinese diaspora communities and solidarity with other racialized groups in anti-racism and anti-oppression-based work. As part of his advocacy work in Montreal’s Chinatown, Mah has been involved with a photo exhibition in the streets of the neighbourhood and is actively working with local government to play music by Chinese artists in the pop-up lounge space near Montreal’s Chinatown gate.

For Mah, the relationship between music and organizing is tied to racial identity formation and knowing oneself: “I wasn’t able to make space consciously before I knew where I was coming from, because I didn’t know what space I wanted to make for myself before that journey had been completed.”

His experiences as a young pianist growing up in a Vancouver suburb were shrouded in expectations from his educators that he should conform to and perfect the music conservatory style of piano playing. “I had to decondition myself in order to open myself up to the possibility of making space.” The first phase of this deconditioning occurred when he moved into the jazz world. “It took several years to reassure myself that what I was doing was not wrong. I had to unlearn things that I was taught in classical music to fully embrace playing jazz.” Eventually, though, Mah also became disillusioned with the institutional form of jazz education. “The ways that success and creativity are measured are based on things like output. How many things have you achieved? In jazz school, creativity is no longer okay by itself. It must be measured and standardized, which ends up stifling creativity. I experienced a different kind of reconditioning by exposing myself to different types of music outside the usual bebop and hard bop canons.”

Mah’s musical sensibilities changed significantly following an invitation to host a community radio show on Simon Fraser University’s CJSF 90.1FM. “I remember walking through that music library on my first day—there were, like, 50,000 CDs in there and I had never heard of any of those artists. I realized that I don’t have to make my place according to mainstream rules.” Releasing music as Rhythm & Hues, Mah skirts the music-industry expectations and creates compositions that combine jazz improvisation with the music of Colombia’s Atlantic coast and Senegal. “The hybridity in my composed music comes from a point of self-awareness around my position and privilege. As an artist from a privileged Western country, I did not want to do music that is not from my place; I wanted to do something that was true to myself without being extractive or being appropriative.”

This spirit of respectful cultural blending also permeates Mah’s practice as a DJ. Known for his extensive vinyl collection—running the gamut of the Afro-Latin-Brazilian-Caribbean musical spectrum—he is deeply invested in expressing the sociocultural impact of these traditions. “The more I dove into Afro-Caribbean music the more I realized how hybrid it all was. All the music we like, it’s all hybrid music, whether it’s come about because of something like the transatlantic slave trade, or because of repressed groups being forced to flee and mix with other people. Those moments of mixture influence all the popular genres, from house to rock, R&B to soul and jazz.” Mah is invested in highlighting the significance of the margins in all he pursues. “I refuse to play into dominant narratives. I’m trying to play music that’s honouring the otherness and the beauty and the values of all of these musics that aren’t Western.”

Parker Mah and respectfulchild have both contended with finding space for themselves and for their particular articulation of what it means to be a musician of Chinese descent in Canada. While both artists create within different musical traditions, they share a desire to find reflections of themselves around them, which speaks to the inspiration they find in Canada’s Chinatowns.

“Chinatown is important because in places where the Chinatown has not survived, that memory and the contributions of those people have been erased from the dominant collective memory,” explains Mah. “I didn’t learn about Chinese Canadian history in school—things like the Head Tax and the Exclusion Act. If Chinatowns don’t exist, it’s like saying anything other than the dominant culture is not worth preserving.” Whether it be through a commitment to the ancestors through a sculptural installation piece or a celebration of music’s ability to fuse cultures, these artists strive to find their own authentic ways to embody a counterpoint to the dominant culture and to bring the margins into focus in their respective practices. Music is their resistance, as they take a defiant stand where few Canadian musicians of Chinese descent have gone before them.

PHOTOS: Photos of respectfulchild by Blaine Campbell; photo of Parker Mah holding a vinyl LP at the launch of Asian Night Market by Kimura Byol; bottom photo of Parker Mah by Guy L'Heureux.

FYI: A Haphazard Handbook of Artists & Organizers across Chinatown is a collection of essays and conversations between six collectives of community-based artists and grassroots organizers who are working in and around their cities’ Chinatowns. A project of Tea Base, the handbook was published in August 2021 and edited by Florence Yee. Find it here.

ON THE CD: Singe 猿 (Parker Mah); s.a.d. (respectfulchild)