IN 2013, NASA CONFIRMED THAT the Voyager 1 probe had become the first manmade object to cross the heliopause, leaving the bounds of our solar system and entering interstellar space. In addition to its scientific instruments, Voyager 1 was famously carrying a Golden Record entitled The Sounds of Earth. Put together by a committee led by noted cosmologist Carl Sagan, the disc was literally a phonograph record pressed on gold-plated copper, that even came with an accompanying stylus, in order to act as a sonic time capsule of planet Earth, for the benefit of spacefaring extraterrestrial civilizations. The record offered alien listeners a selection of natural sounds and music ranging from Bach to Chuck Berry. The record also contained images of Earth and directions on how to find it—a fun fact since exploited by paranoid science-fiction stories.

When the news broke of Voyager 1’s adieu to our solar system, never to return, Canadian composer Andrew Staniland was working on a commission from classical guitarist Rob MacDonald. The piece, Dreaded Sea Voyage—included in Talking Down The Tiger, Staniland’s new Naxos CD of works for instruments and electronics—took its title from an eerie line in a biography of Gustav Mahler: “For several months, Mahler had been living in half-acknowledged dread of the impending sea voyage.” Another inspiration was a sensationalistic Toronto Star headline regarding a respected physicist’s warning about our species’ risk to our planet: “Stephen Hawking says we must flee Earth.” But it was Voyager 1’s precious cultural cargo that provided the thematic and structural basis for the piece.

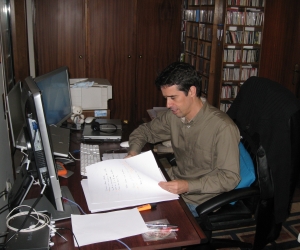

“Can you imagine being the person who got to choose what was on that record?” Staniland enthuses over coffee at the espresso bar of Toronto’s Royal Conservatory of Music. “Having to choose sounds to represent Earth?”

What composer doesn’t want, much like the clichéd mad scientist, to play God—or at least, Carl Sagan? The late Cosmos guru’s committee worked valiantly to represent a diversity of human culture through music: from Navajo chants and Peruvian panpipes to Glenn Gould playing The Well-Tempered Clavier and Mr. Berry singing “Johnny B. Goode.” To score Dreaded Sea Voyage, Staniland chose a few excerpts from the Golden Record and transcribed them into a computer scoring program, and then, as he describes in his liner notes, “began modulating different pieces together, using an extrapolated Frequency Modulation technique, breeding one measure of a piece with a measure from another.”

As he explains the process in layman’s terms, “I took the Mozart and the Bach, smushed them together and made some pitch material.” During the electronic section of the piece, the composer exploited the tones of the Javanese gamelan, which travelled nineteen billion kilometres aboard Voyager 1. “I think it’s just fascinating,” Staniland enthuses over the Golden Record idea. “It’s a wonderful question to ask somebody: if you had to put something in a time capsule of any kind, what would you put in to say you were here?”

Born in Red Deer, Alberta, in 1977—the same year Voyager 1 began its journey to the stars—Staniland grew up in the provincial capital, Edmonton. He got into music through playing guitar, and began playing in heavy-metal bands as a preteen. “I think I was always a composer,” he says. “I remember coming up with colour-based notation schemes to record my pieces for guitar, which had multicoloured strings. I was always writing, in one way or another, through high school; I had a great music teacher named David Smith, who really fanned the flames of curiosity about music.” Staniland studied jazz and arranging at Edmonton’s Grant MacEwan Community College (now MacEwan University), where he seriously began to hone his composition chops, studying with Gordon Nicholson. After follow-up studies in classical guitar at the University of Lethbridge, Alberta, he moved east to pursue masters and doctorate degrees in composition at the University of Toronto. Staniland became a noted talent among the youngish generation of Toronto-bred new-music artists, alongside his regular performers MacDonald, percussionist Ryan Scott, and saxophonist Wallace Halladay, plus fellow composers Brian Current and Scott Good. (“My musical family,” he calls them). During his time in Toronto, Staniland garnered numerous awards and notices for his compositions, including the 2009 National Grand Prize in Evolution, a contemporary music competition created by CBC Radio 2 and Espace musique in partnership with the Banff Centre. As an affiliate composer to the Toronto Symphony Orchestra from 2006 to 2009, Staniland composed the orchestral piece Four Angels, which he considers his finest achievement.

But the composer has voyaged ever further east across the Canadian dominion; since 2010, Staniland has called St. John’s, Newfoundland, home. A city with a strong new-music tradition, thanks to institutions such as the biennial Sound Symposium and the improvising ensemble The Black Auks, St. John’s has become an important hub for creative music in Canada, despite its geographical remoteness. Upon visiting Newfoundland with Toronto new-music collective Toca Loca for Sound Symposium 2006, Staniland quickly fell in love with The Rock, as the island province is known. “I remember phoning my wife from a pay phone and saying, ‘This place is just amazing. You gotta check it out.’ I didn’t know that a couple of years later I’d be living there.” Although he has called Newfoundland home for half a decade—and is a faculty member at Memorial University, and started a family on The Rock—Staniland still has alien status. “There’s a name for us: the CFAs, the Come-From-Aways,” he tells me during out talk in Toronto. “I don’t think my youngest son, who was born there, will ever be considered to be from there. I think you have to have lived there a few generations . . . I do love it though!”

The day of our conversation, Staniland was in Toronto to attend the premiere of Large Hadron Collider, his brand new commission for Esprit Orchestra. “Alex Pauk [Esprit artistic director] and I have been trying to get a piece together for about four of five years now,” he explains. “He finally phoned about half a year ago and said, ‘Let’s just do it.’ He didn’t have many guiding principles for me, other than that he wanted it to be about seven minutes long, and he didn’t want it to wallow in the pianissimo register for the entire piece. That was the only information he gave me at the time, so off I went. And I wrote about what I was interested in at the time, the Large Hadron Collider [particle accelerator]. I actually went to visit it a few years ago, at CERN [European Organization for Nuclear Research] in Switzerland. It’s just this enormous tunnel under the ground, and it’s the biggest, most elaborate machine ever built.”

All to find the smallest thing?

“Yeah, just to see what’s there. It’s incredible how far curiosity can drive you.”

Though space and science appear to be abiding obsessions for Staniland, they are just two among many diverse interests. “I’m easily excitable and easily interested in many things. If I had a superpower, it would be that I’m easily interested—I don’t find it difficult to get inspired.”

Behold: Curiosity Man!

Staniland laughs, then turns serious for a moment: “Being curious is an incredible driver of creativity and innovation.”

In scoring Large Hadron Collider, Staniland makes the orchestra run some laps in an attempt to suggest the velocity of the machine that inspired the piece. “There’s actually been quite a lot of data sonofication from CERN, and people have already made musical pieces out of it. I went more for the metaphorical angle. To find out what’s inside these small particles, we’re smashing them open—it’s a brute force investigation. Imagine if you were investigating something else, and you smashed it open to see what’s there!”

Well, there’s no other way to get around the strong nuclear force.

“And luckily there’s no shortage of particles, so they’re not precious in any way. The piece takes an idea and accelerates in a certain direction until it reaches a maximum velocity. Then I stop that idea a third of the way through the piece, and then accelerate another idea in the opposite direction. And then you put them in the same tube until they hit each other, and you see what’s there.”

You might think that Curiosity Man composes as quickly as his metaphorical particles dash about, but the opposite is true. “The evolution of these things is always very long. It’s very rare [that] you get the call and seven months later you’re at the piece. I usually work two or three years in advance. So you’re not the same person you were when you dropped the question. So you really have to remember where you were, and you have to continually reinvent the project.” One wonders if he ever worries about losing interest or connection with pieces when they’re incubating for so long. “I don’t engage with them until it’s time. And like other things in life, the most attractive thing is the very next piece you’re going to do—not the one you’re in, because it’s work at that point! It’s the one just out of reach—‘Oh, I can’t wait to dig into this!’ . . . That’s where the magic is.”

If, as Arthur C. Clarke once sagely pointed out, any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic, it would then make sense that a musical musician like Staniland would want to invent some technology. The composer built a lab at Memorial, which he describes as a “state-of-the-art research and teaching facility,” and recruited a crew of engineers to help solve a common problem in contemporary electronic music: the introversion of performance. It’s a familiar criticism of live electronic shows: the musician staring at his or her laptop, unengaged with the audience, and vice versa. (The “It looks like he’s checking his email!” complaint.) When the audience can’t see what the performer is doing, there is little “cause and effect” to enjoy.

Their solution was an instrument, the Arc, a four-pointed star with an oaken body encasing electronics, that sits comfortably upright on a lap, much like a guitar, or perhaps an accordion. The Arc features thirty-two force-sensitive pads and eight touch faders that operate without a slider mechanism, and through these controls the user can manipulate audio software such as Ableton.

“There’s something really nice about using something anthropomorphic. As soon as you can kind of shape something, it becomes something else,” says co-inventor Staniland.

The Arc is going through a transformation of its own, as one of the graduate students who helped develop it, Scott Stevenson, is working to bring it to market, under its new name, the Mune. Product shots play upon the woodgrain tactility and plug-and-play appeal of the electric guitar, though the Mune is clearly something new and different.

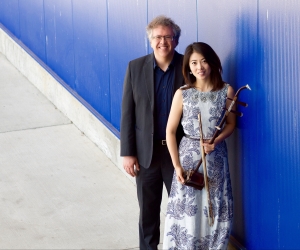

Otherwise, Staniland is happy to be a composer rather than an entrepreneur, and is excited about two new premieres on the horizon: Choro, which was performed by Russia’s Grisha Goryachev and Brazil’s Fabio Zanon (“two of the greatest guitarists in the world,” according to the composer) at a May 2015 concert presented by Soundstreams at the 21C Music Festival in Toronto; and The Ocean Is Full of Its Own Collapse, a “huge” thirty-five-minute piece for violin, piano, and narrator (for its premiere, ballerina Evelyn Hart), based on the tragic 1982 sinking of the offshore oil rig the Ocean Ranger on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, and performed at Ottawa Chamberfest in July 2015.

Asked if there’s one aspect of these maiden voyages that most excites him, Curosity Man simply exclaims, “It’s all exciting!”