“Why don’t you come by my place and I can sell you the CDs you’re seeking,” said the voice on the phone. It was the spring of 2005, I was in Amsterdam and looking for recordings from the Dutch label Unsounds. The voice on the other end of the line was that of Dutch-Cypriot composer Yannis Kyriakides, whose work I had encountered years earlier and who, I had just discovered, is a partner in the hard-to-find recording label. We set a time to meet later in the week, and as I quickly scribbled down the details, I could feel my pulse racing at the prospect of meeting Kyriakides face-to-face. While I have met composers in the flesh before, I had only encountered Yannis Kyriakides through his music, which at that time I found completely exhilarating and unlike anything I had heard before.

At that time Yannis and his wife, singer Ayelet Harpaz (who has performed many of his works), were living in a small house in Amsterdam’s Old West district, just off the bustling Ten Kate Market. As I stepped in the front door of their typically narrow and cozy Amsterdam home, I quickly became acquainted with this composer’s world through his surroundings. Dividing the kitchen and the living room was a wall of books, mostly of ancient philosophy—which I later learned has served as a strong influence on his work. The stairs up to a small bedroom loft angled up off from the kitchen counter!—an ingenious design solution to tight living quarters, and very fitting for the home of a composer who has an interest in playing with sensory space. At this time, Ayelet was very pregnant with their first child. I thought, How does she get up those crazy stairs at night? Beyond the living room, through a set of glass panels I could see a small garden and a little shed. Perhaps they were using that as their bedroom? Yannis informed me that the shed was his studio, which he was reluctant to give up, given how busy he was with his work.

In the Dutch tradition of langskomen, my visit became more than just a quick pop-in to grab a bundle of much-coveted recordings, but an afternoon chat over a pot of tea. Our conversation meandered through a number of topics: the state of new music in Amsterdam, why record shops were having trouble staying open (and where to find the few good ones that remained), and the distinctions between living as a composer in the Netherlands versus doing so in Canada. While the subjects ranged widely, we talked very little about our own work. This was time for us to make acquaintance and be sociable, not conduct business.

Yannis’ career was hitting its stride at the time (and has continued to accelerate successfully to this day). His catalogue of commissions had reached over fifty works; his

third electronic music-theatre piece, Escamotage, was about to be premiered by the Staatsoper Stuttgart; and Wordless, his intriguing multimedia electronics piece, had received a local performance by STEIM (the Netherlands foundation for electronic music) just a month before my arrival.

Of his works from this time, not to mention the numerous others in development, Wordless marked what I considered to be a new creative arrival in Kyriakides’ artistic explorations of music as language and narrative as musical material. The piece consists of twelve sound portraits based on interviews with residents of Brussels. The content was drawn from the growing BNA-BBOT archives, a public audio project that records and shares the stories of ordinary Belgian citizens. The core of Wordless involves removing all of the words from the selected interviews to leave only the interstitial sounds—hesitations, breathing, non-verbal vocal reactions, and environmental backgrounds. By stripping away the surface language, another layer of communication comes into focus—one that is more emotive and more revealing than that which was expressed in the words of the original interviews.

Kyriakides then took these new wordless “interviews” and set them into musical structures composed of wave-based electronic sounds, resonances, pulses, and noise, to amplify the non-verbal narratives. What results is a highly intimate sound portrait of each interviewee. Kyriakides further integrated his other artistic interests in spatiality, perception, and sonic experience through additional audio-visual layers. The presentation of Wordless calls for live playback over a four-channel system, the interviewee voices to be heard through headphones while the electronic sounds are played back through loudspeakers, creating a sense of inside and outside sound worlds—an expanded physical awareness of the listening space. Yet another element of the work is a video display of texts describing the interviewees and their stories, which potentially affect the listener's perceptions of the individuals depicted in each sound portrait.

Wordless represented a new level of synthesis among Yannis’ artistic objectives and, as such, it has been growing in recognition. Not only has it gone on to receive subsequent presentations on two continents but it also has received an Honourable Mention in the Digital Music category of the 2006 Prix Ars Electronica. While I was disappointed to have missed the installation version, Wordless since has been released in a special format on Unsounds.

Encounter with new forms

The encounter that first brought Kyriakides’ music to my attention took place in the spring of 2002 at Esprit Orchestra’s first New Wave Composers Festival. Beyond creating a platform for young Canadian composers to meet, share their music, and exchange ideas, artistic director Alex Pauk had invited a number of guest filmmakers and composers from Holland to Canada to share their collaborative projects. One of these projects—a short, black-and-white dance film by Ester Eva Damen, with choreography by Angela Kohnlein, titled RHOmbos—made an impact that has stuck with me to this day.

The work was filmed from a unique perspective: the camera, rather than facing the dancers directly, was positioned in the centre of the performance space, where it was spun frenetically on its horizontal axis, with continuing deceleration to a point of final rest. As a result, we (the audience) only got rare glimpses of the choreography as it unfolded in the film’s space. It wasn’t until the camera came to its eventual standstill that we could get a firm sense of the space and the dancers that inhabited it, who by this time were completely spent from moving at the same frantic pace as the camera’s spinning. The film’s music was fresh to my ears: enticing, atmospheric, unsettling yet completely integrated with the concept of the work. This was my introduction to the sound world of Yannis Kyriakides. And I was sure I wanted to know more.

At the time I experienced that film, I little knew how much it had to say about Kyriakides’ practice. Its merging of media, performance practices, various sound sources, and unconventional structures touched on many of the key elements that create a through-line from his earliest works, such as No One is Filming—an experiment in imaginary film music for a non-existent film—to his most current projects. It is through this hybridization of various elements that Kyriakides hopes to create a space where the traditional hierarchies of music are de-centred and audiences are offered new forms of musical experience. “I want the audience to come to the music not entirely sure how to listen to it,” he declares. “I like to think that a small dose of disorientation is good for breaking down our rigid habits of perception.”

Encounter with language

Despite an already burgeoning career in Europe, with more than twenty premières at major festivals and concert halls to his credit, as well as the 2000 Gaudeamus International Composition Prize, Kyriakides’ work had yet to find its way to North American concert stages. Nonetheless, mesmerized by RHOmbos, I immediately managed to seek out and purchase a copy of Kyriakides’ debut solo CD, a conSPIracy cantata (known as SPI for short) on the Unsounds label. By experiencing SPI on CD, I perceived Kyriakides’ creative practice even more clearly.

The CD takes its title from the forty-five-minute electronic cantata for two alto voices, piano, radio, and electronics that fills the better part of the disc. The work juxtaposes two forms of cryptic message communication: the mysterious world of “spy number transmissions” on shortwave radio—cryptic one-way numeric communications that have been documented and popularized as part of the Conet Project, issued on CD in 1997—and the enigmatic utterings of the ancient oracle of Delphi. The piece weaves together an archaic sound-world with the chilling atmosphere of Cold War subterfuge, all reinforced by electronic sounds that are constructed of layered radio transmissions, noise textures, pre-recorded voices, and sampled piano.

SPI is a stunning example of Kyriakides’ continuing fascination with the mechanics of communication and its peculiarities, including the potential for innovation, evolution, and failure. In discussing the topic, he tells me, “I find the area where music intersects with language to be an interesting one. I have had an interest in codes and encryption since 1999, when I was inspired by the Number Station transmissions to write SPI. I am fascinated by the spectrum of how music can function on one level, the way language does, or how we can even encode words into music for the sake of economical or clandestine communication. The question of whether or not music is a language is also an interesting one to me, and it lies at the heart of many of my pieces. I also like working with narratives, because I don't believe music ever to be abstract. As opposed to Stravinsky's statement that ‘music cannot express anything but itself,’ I feel that the one thing music can't express is itself. So, there is often a play of narratives on different levels in my pieces.”

As I had discovered in that 2005 trip to Amsterdam, Unsounds was launched by Kyriakides in collaboration with post-punk guitarist and new music improviser Andy Moor and graphic designer Isabelle Vigier. The ongoing project was created as a means to share both Kyriakides’ and Moor’s music, plus the music that the collective admired, without having to ask for anyone’s permission to do so. Since the label’s inaugural release of a conSPIracy cantata, Unsounds has gone on to release fifteen more discs, including music by Robert Ashley, John Butcher, Francisco López, Kaffe Matthews, and many others, as well as documentation of three years of live electronic improvisation that took place at Amsterdam’s popular Kraakgeluiden night.

“It certainly involves a lot of boring work,” admits Kyriakides, “but it’s always been fun . . . especially as a way of making accessible to a larger public what we find beautiful and valuable.”

Managing a label has also affected how he conceives of his own musical output. There were ideas of moving the CD beyond its functions as documentation of existing repertoire or improvisation sessions (Kyriakides regularly improvises with Moor, Butcher, and others) to having it serve as a vehicle for stand-alone projects. However, pursuing this creative path quickly revealed that a CD’s value was amplified by what led up to its creation and the ensuing results. For Kyriakides, the CD is a captured moment in an artistic flux, never an isolated artifact, even if it is the primary medium through which much of the public will be exposed to his artistic work.

Encounter with strategies of interaction

While I have had numerous other experiences with Yannis’ music over the past eight years, my most recent encounter has taken the form of this article, for which we have reignited a transatlantic correspondence. As he hopped from Sweden to Norway to Vienna, attending performances of his work and conducting Ensemble MAE (for which he has served as artistic director since 2005), we have been discussing less about his music and more about the environment in which it is being received, especially given that digitization and the Internet have greatly changed the way we now discover, listen to, and share music with others.

It comes as no surprise that Kyriakides sees these digital developments through his own unique creative lens. “I have certainly been affected by these technological changes. It's difficult not to be. It's also exciting to let these social changes affect my art. I personally feel most inspired when I'm reacting to a new situation, brought on by technological change or social change.” He also has considered these changes in light of his role as label owner, “Economics plays a larger role in our decisions than we often admit. But to think of distribution or audience reach is not a very creative or inspiring starting point. When I speak of reinventing form, I mean to break away from the limits imposed by these very conventions that are created by the music industry or the culture industry.”

Recent experiments with releasing new works on Net labels, such as the Highly Coloured Places project for the Belgium-based Entity, or the Juncture improv CD with Argentinean reed player Lucio Capece for AudioTong, have proved to be unrewarding. “To be honest, because we didn't release these on Unsounds, the experience seemed more impersonal and removed,” he wrote in one of his e-mail replies. “I've even somehow forgotten about them.” The virtual lack of budget and ephemeral format of these recording projects has turned them into a non-event. There is no proofreading of booklets, no error-checking of a CD, no communication with the manufacturer, and no delivery van showing up with a crate of CDs that then must be sent off to various promotion and distribution outlets. All these activities make a CD release somewhat more of a significant event. But not necessarily one that Yannis will miss.

What does this mean for the future of Unsounds then? Many say that the CD is dying. Yet the label just released a run of new albums, including Antichamber, a double-CD set of Kyriakides’ chamber music written over the last ten years. Does the Unsounds collective believe that there is still room for the CD as a format for disseminating new works in today’s digital download environment? “We've talked about this at length recently with the label,” wrote Yannis. “Certainly, it's true that we can't shift as many CDs as before. A lot of our distributors have folded, and we’ve had to limit the number of CDs we produce for each release. While the format’s days are indeed numbered, for the moment it still makes sense to release a limited run of each new CD and to make them available online. I think within a year or two the CD won't even make sense as a promotional tool. That's why I was in a hurry to release Antichamber.”

With any shift in medium comes also a change in function and use. The shifts that have been made by the distribution and diffusion of music through the Internet undoubtedly affected Kyriakides’ thinking about sensory space [see sidebar]. “Indeed, the Internet has limited scope for delivering as full an experience as what we can experience live, at least for the time being. It’s not simply about the limited bandwidth and the effect on the sonic range. It is also tied up with the very particular habits of listening online. For instance, one can never really abandon oneself totally to music online. The experience is too cerebral. Furthermore, the habit of surfing through information overwhelms other motivations. One is more likely to click through to the next bit of sound data than to patiently listen to the end. However, I do think that releasing music online will gradually alter the form, such as through eliminating time restrictions and developing strategies of interaction that more deeply engage the listener.”

One such experiment in form and strategies of interaction is Kyriakides’ QFO, an online collaborative project developed with Isabelle Vigier and commissioned by the new U.K. agency Sound and Music. QFO: on visiting Sir Walter Cope’s cabinet of curiosities takes the form of what could be considered a seventeenth-century travel journal, adapted to contemporary sensibilities and online interactivity. In fact, the text is taken from a Swiss traveller’s description of this cabinet of curiosities that he witnessed in London in 1599. Each of the journal’s fifty pages catalogue an item in the cabinet, in text and sometimes image, accompanied by composed electronic sounds of varying durations, but none longer than ten seconds. QFO, which stands for Queer Foreign Objects, translates Kyriakides’ past interests with music and text projection to the Web.

Precedents to QFO include several audio-visual pieces, like Mnemonist S. and Dreams of the Blind, which take on the form of what Kyriakides calls videotext. Found texts, interviews, and personal stories are projected at a rhythmic pace in keeping with a musical score inspired by the content. These videotext works emphasize his creative relationship with language even more assertively than before. But what is perhaps even more noticeable is how, through their minimalism, they are very adaptable to the Internet and can potentially be more easily absorbed by an online audience—say, through his Yannisky YouTube channel. “Neither of these pieces was actually conceived for the Internet. It is a happy coincidence, but one which I'm happy to continue,” he wrote. “Perhaps they are better suited to the Web because there is a strong weight put on the textual information. There is a new series of text-based pieces for violin and video in the pipeline, but it would be interesting to develop some more Web-only pieces that go further into the field of musical narratives. I'm also planning in the next text piece to work directly with a writer or poet, to explore from a more fundamental level what we can do with language and music.”

Even with the success of the videotext pieces online, Kyriakides is anxious about this form of dissemination, “I have a fear that the tailoring of Internet-based music to fit the listener's taste or mood will become more prevalent, and will become part of the compositional strategies engaged by musicians in the future.” But he does have a glimmer of hope for what is to come. “No doubt there will always be people who do something exciting and interesting and subversive with this.” No doubt Yannis Kyriakides is already among them.

So, what will be my next encounter with Yannis Kyriakides? I have a dream that Contact Contemporary Music will present his Mnemonist S. in Toronto’s Yonge-Dundas Square during one of their New Music Marathons, using the huge advertising video boards to project videotext to amplified live music—an artistic subversion of the City’s attempt to recreate the commercial excitement of New York City’s Times Square. Contact was to bring Kyriakides’ Dreams of the Blind to Toronto this past autumn, but conflicting schedules prevented him from completing the necessary arrangement for the ensemble. Until either of these projects become a reality, I will have to content myself with virtual experiences of his videotext pieces and with my coveted stack of Unsounds discs.

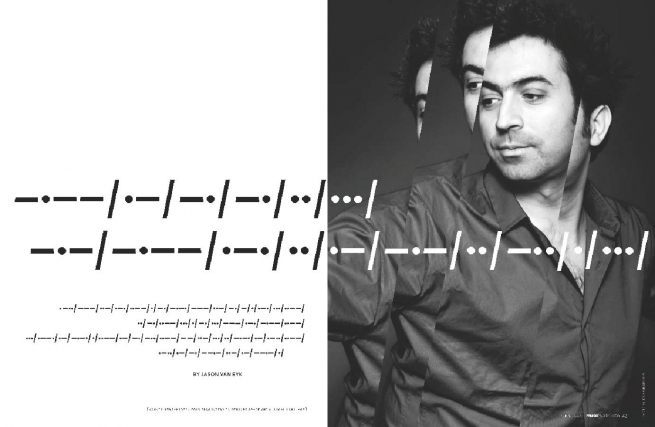

Audio: Music in a Foreign Language (2007). Composed by Yannis Kyriakides. Image: Yannis Kyriakides. Image by: Jochem Jurgens. Image designed by: Lucinda Wallace