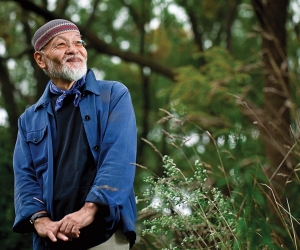

The world of improvised music has spawned a core of musician–organizers who have built scenes and networks and record labels to support and extend the music. Few, however, have achieved what Éric Normand has, creating a hotbed of free improvisation in the relatively isolated little city of Rimouski, more than 500 kilometres northeast of Montreal along the southern shore of the St. Lawrence River.

Normand’s accomplishments are remarkable. He’s created twenty-two editions of Rencontres de Musiques Spontanées (Spontaneous Music meetings) in Rimouski, bringing musicians from twenty-five countries to attend. He has also enlisted numerous celebrated guests to conduct workshops and created a record label, Tour de Bras, to release his own work and that of his associates. Above all, he’s developed GGRIL (Grand Groupe Régional d’Improvisation Libérée), an improvising orchestra of around a dozen members that’s been active for a decade and has recently toured in Europe.

Normand started out even further east, growing up in the far smaller Mont-Joli where he was born in 1977. His involvement in music came early and his taste has always run toward the vigorous and immediate. “I started playing music at twelve, as a drummer in an absurd punk band,” he recalls. “I loved bands with politically engaged texts: The Clash, Dead Kennedys, and Citizen Fish were some of my favourites, along with provocative French punk bands like Bérurier Noir and OTH, and the local [Quebec] scene.”

From those beginnings, Normand started to explore further. “As a teenager I wanted to dig jazz a bit, so I asked a friend who was listening to it. He said, ‘Miles and Coltrane are the two big things.’ So I went to the record store and bought what I found: Kind of Blue and Stellar Regions. At the time the Miles album sounded like grandfather music, but Coltrane was a revelation for me.

“So I started to grab old LPs of modern jazz (this was before they cost thirty dollars) and made my way through that story—from Ellington to Gil Evans, from Monk to Albert Ayler, Steve Lacy, Sonny Sharrock, Zorn’s bands, and also AMM and the English free-improv scene.”

The music service of Radio-Canada—the French-language counterpart of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation—broadened his purview further: “[Back then] it was still an artistically oriented radio network and was producing a lot of experimental content in close relation with artists. As I was living in a remote location, it was my simplest contact with new music. My number one radio show was Navire Night with Hélène Prévost. I listened and recorded it every week. That’s where I discovered Fred Frith, Xavier Charles, John Butcher, Luc Ferrari and, of course, all the Québecois musicians linked to musique actuelle, such as René Lussier, Jean Derome, and others. If I were that age today, I wouldn’t have that access to this music. Now the CBC only plays pop-oriented stuff and there are fewer and fewer independent record stores.

“During my university years studying French literature, I went into more intellectual music, contemporary music, and also soundscape and more conceptual sound artists. Through music and writing I went into Cage, Kagel, Berio, Aperghis, Lucier.”

If Normand was an early connoisseur of outside music, he also understood that the isolation of his hometown made it conducive to outsider art. “Rimouski is a pretty small place, but I believe that some interesting things are now coming from outside major cities, where money is a mess for musicians. I felt that I could do something great here, with all the places, with the people. So I started to organize some concerts. Not only my stuff, but trying to bring all kinds of sounds here.

“The Québecois artist Serge Lemoyne said in the ’70s, ‘The artist of today is a producer; he is not the skilled craftsman, but the one who makes things happen.’ I can relate to this. I make no distinction between playing my own music or bringing great musicians to the same room. In a small place, you have room, and you have time. John Cage said that everything is possible, if you start from nothing. In this place, outside the usual circuits, I’m just trying to make possible the expression of more personal views on music-making, outside of pop, outside the academic, outside the hip.

“I’ve always felt my music to be so different from what was happening in Montreal, so I started shaking things here, and now we have a scene, a bunch of devoted musicians having a deep personal practice. I’m really happy to see that this music is now growing outside of me, to see people doing great, to see Tom Jacques building microtonal instruments, to see Olivier D’Amours digging electric music; to see Alexandre Robichaud bringing trumpet to the extreme. I don’t know if I’ve created it, but I’ve surely excited it, made some things possible and concrete. Since Montreal is the only big city in Quebec, it’s just not normal to have us existing and running a big band in Rimouski. I like it. For me it’s a creative position.”

Founded in 2004, GGRIL literally began with Normand’s enthusiasm. “I had wanted for a while to have an improvising orchestra. At the very beginning, it was pretty much a community thing with nonprofessional musicians, open to everyone who wanted to come to rehearsal. I was interested in the history of this music and wanted to share it with other people. But it turned out too well to leave it there. With the deep engagement of musicians like [violinist] Raphaël Arsenault, [guitarist] Robert Bastien, [guitarist] Olivier D’Amours, and [violinist] Catherine Massicotte, the band became so good that I wanted to bring some great musicians to work with us, to learn from their experience, their feelings.

“I’ve always felt the need to go forward with open forms, so we’ve tried a lot of different ways to do ensemble improvisation, from graphic scores to totally free and also some partly written music. I was pretty influenced by [writers] like Georges Perec, Raymond Queneau, and Italo Calvino, and I was thinking that we could be free through constraints. We realized that we are more stimulated by games, with pieces that have no fixed beginning or end but that can surprise us all the time. That’s why [we used] conduction as well as card games. Conduction turned out to be a good tool for us—not a finality, but a tool, part of a process to do good group music. Any member of the band can take the floor and conduct at any moment. There is no hierarchy.

“The band is really democratic. We want to learn from the meetings with others and also to do things our own way. We’re not authoritarians; we defend freedom. Our first and most important rule is: you are free to not obey the rules.

“As [novelist Italo] Calvino said, we chose légèreté over gravity. That doesn’t mean that we cannot be serious in the music-making. but we didn’t want to legitimate our music by theories, we wanted the music to be good by itself. And we all wanted to have fun together. Then we did this with so many great musicians, and each time it was a particular thing with different sensibilities, that influenced our own work while letting it go its own way.”

Improvising with a big band is not something to be learned from books, Normand says, so GGRIL developed its own thing by working with “great people”—musician–organizers such as Evan Parker, Jean Derome, Joëlle Léandre, Ingrid Laubrock, Michael Fischer (Vienna Improvisers Orchestra), and Olivier Benoit (Orchestre National de Jazz). “The first meetings were pretty challenging for some band members,” Normand continues, “and then we got more and more confident, understanding that playing with these legends is not about ego or success, but about sharing an important and rare event, and also about defending this practice. Now the band has its own language for conducting and the music is still [getting] better and better.”

GGRIL’s original sound is likely a result of this unique combination of isolation and access. Its identity as a regional band shows in the mix of instruments, favouring multiple electric guitars and basses and a slightly irregular assortment of strings, accordion, and relatively isolated winds, all contributing to a sound. There are subliminal traces of folk idioms as well. On the other hand, GGRIL has worked with as broad a spectrum of guest conductors and soloists as any band located in a metropolis—from its ongoing associations with Danielle P. Roger and Derome to recent international guests.

“The extended work with Jean Derome was, maybe, our first big evolution in conduction,” remarks Normand, reflecting on those early meetings. “Comparing Jean’s complex signs to our methods was relevant and helped us to figure out what we wanted to conduct and what we wanted to be free. The work with [French clarinetist] Xavier Charles has also been important. He only asks us to listen in particular ways and never tells us what to play. We’ve learned that we don’t want to use a thousand signs, that it’s better to keep it simple and organic. The point is not to focus on the language, but on the communication.”

Meanwhile, GGRIL is finding increasing opportunity to travel and interact with other improvising groups. In March 2016, GGRIL embarked on a remarkable European tour, engaging with other musicians, ensembles, and conductors: across ten performances in Austria, France, and Italy the band played with great ensembles such as Vienna Improvisers Orchestra, Muzzix, Le UN, On Ceim, Omedoc and Le Lobe, and also with bassist Barre Phillips, cellist Emmanuel Cremer, and guitarist Jean-Sébastien Mariage, among others. “It brought the band to a higher level of interaction in the music, but also in performing and living and being all together,” Normand says. “I’m now working to take the band to the U.S.A. and Japan in coming years. That’s how it should be if we want to grow and be a band that counts, that move things.”

Normand’s creativity is immediate and engaged, evident in his active do-it-yourself instrument-building and a host of musical projects. Unhappy with commercially available electric basses, he decided to start building his own. “I built [one] out of hard oak and made the nut out of a roast beef bone. It has a short scale that I tune higher than normal, because I wanted a lot of string tension but easy action. I also paid particular attention to electronics and contacted a brand that does handmade pickups to get versatile sound settings and a lot of harmonics.”

He feels the same way about effects pedals. “I love fuzz boxes, mostly those with a lot of harmonics and noncompressed sound. They can make the bass sound like Albert Ayler’s tenor sax. Wow!

“I tried a lot and didn’t want to pay, say, three hundred dollars, for a boutique pedal that is mostly built out of modern components. Even those sold as vintage fuzz are driven by modern silicon shit. So I decided to DIY. I ordered a bunch of different, old-style transistors from Russia, Bulgaria, and Japan. I started to experiment and it turned out pretty well. They’re all a bit unstable and can break anytime, but that’s all part of the fun. I’ve built one for Martin Tétreault: The Tetronic. He used it for a couple of years and then it broke. That’s life. I have a new one in mind. It will be a present when I have time to build it.

“It’s the same as free music. Doing this stuff is a big statement for me, against the music business, against genres and for the creative human being. I follow my curiosity. Improvisation is nomadic music.”

It’s in the small groups that you hear how fully developed Normand’s musical identity is, whether he’s playing anarcho-folk with Nova Scotia-based guitarist Arthur Bull or in a “non-idiomatic” duo with Xavier Charles. “Most of my long-lasting projects are duos—not usually people I can play with really often, but people with whom I have a good connection, with whom I share common interests in sound. I feel that it’s a good context to invent new languages, new connections, with pretty great musicians. My work with [reed player] Philippe Lauzier in the duo Not the Music is really important for me and always evolving. We now want to go forward with a new project.

“Arthur Bull is another precious collaborator. We’re doing all kinds of things together, but we’re focusing on the folk-song project called The Surruralists. We sing old songs from Quebec, Cajun songs, blues and also some of the Clash or Ornette Coleman in a kind of freak-out folk duo with guitar, banjo, harmonica, bass, and both singing. It’s really fun and really free in a way. We don’t have to care about being serious or modern, we just have fun and do what we want.”

His duos with Charles and [Australian reed player] Jim Denley are equally stimulating and challenging. “They are such fantastic players with really unique languages,” he continues. “I have albums coming with both that I’m pretty happy about. I think this free-improv duo work is the most serious: It sounds like it comes out of my being.”

Normand’s most recent release of his own music is Mattempa, which he describes as chamber music. It’s performed by a quintet that includes Lauzier on reeds and GGRIL members Raphaël Arsenault on violin and bowed instruments constructed by Normand, Alexandre Robichaud on pocket trumpet, and Antoine Létourneau-Berger on percussion, with Normand on electric bass and amplified branches. Relatively subdued, it’s music of subtle resonance, filled with unusual textures, voices, and connections.

He also has several projects coming to fruition, including recordings of protest songs and a kind of jazz band called The Jazz Mess, complete with a remodelled version of the cover of an old Art Blakey LP. For 2017, Normand is working on a guitar quintet with French guitarists Julien Desprez and Jean-Sébastien Mariage, along with Quebec musicians Bernard Falaise and Alexandre St-Onge, and GGRIL will pursue new work with Lori Freedman, Gus Garside, Ingrid Laubrock, and Ab Baars.

“We are still moving, still going forward.”

Photo of Éric Normand by: Marie-Eve Campbell.