A maze of thin, transparent hose bundled by lock ties runs along the walls and floors of a spacious studio painted white from floor to ceiling. At the back of the studio near a tool and supply room, an air compressor kicks into action with a thump. Hissing air begins filling the lengthy veins of hose and provides an airy prelude to a conversation, as if the studio walls were leaking oxygen. Behind a worktable littered with latex balloons, plastic tubes, and tools, stands Jean-François Laporte, solidly built, with a shaved head that renders his large inquisitive eyes even more engaging. He checks for air leaks, listens to switches clicking, and adjusts the mechanized arm that sets in motion the hammer of tu-yo, his invented wind instrument.

Jean-François Laporte is a Montreal artist-explorer of insatiable curiosity and drive. I am witnessing him in action at the headquarters of Contemporary Totems, his aptly named production company, on the fourth floor of an industrial building near the railroad tracks in Montreal’s Mile End neighbourhood. Serving simultaneously as a lab, studio, office, workshop, and performance space, this is where Laporte’s invented instruments, which he calls totems, take life, growing from conception to fabrication to performance. Seeing his instruments displayed in the studio in their intimate and fetish-like uniqueness explains his company’s name. You sense that a wizard with tools is working late hours and that the instruments represent more than their sound-making qualities. Laporte is approaching the end of his second decade of sound invention, which has included a 2002–2003 stint at highly reputed IRCAM in Paris, international touring and co-production, numerous awards, and ongoing commissions.

“I don’t fit very well into the contemporary music world,” claims Laporte. “My work isn’t taken seriously.” He is poker faced, shop-worker-ready, looking for the right tool. He waves a yellow balloon in one hand, and with the other demonstrates how the position of the plastic lock ties, used as hammers to beat latex membranes, varies timbre. “I play balloons.” Nothing appears clownish about the latex stretched over aluminum pipe or wide-mouthed steel bowls. The look is studied, homemade industrial design: clean, no pretense, but made to be viewed.

Attractive, integrated visual elements are recent additions to his family of sound installations. Gaining attention in the visual arts world, Laporte captures and manipulates images of his instruments in performance in order to visually enhance the projects while also demonstrating how they make sound. In the context of autonomous installations, the visuals are an extension and substitution of his role as a performer. All of his projects currently in development take visual production into account and are planned to function as installations. It’s indicative of his current interest that when travelling, he goes more to exhibitions and contemporary dance than to music events. While his engagement with the visual arts milieu is currently increasing because he thinks his work fits best there, he nonetheless assures a flexibility in his creations that allows for a variety of presentation platforms, including concerts.

Physical, sensorial sound is Laporte’s obsession. He is totally engaged in the understanding and manipulation of sound as concrete material, and chooses acoustic sound production for his invented instruments over digital sound abstraction. He employs computer applications to activate, control, and observe his music, but sounds are made and experienced exclusively acoustically. Despite an increasing tendency towards robotic control and refined mechanical gearing in current projects, nature’s physical and sound phenomena are the essential references for Laporte. This is only one of his numerous dichotomies. His sounds smack of industrial thunder and humming, yet mythical names denote the powerful forces that inspire his instruments: Psukhô (breath), Kyokkoufu (winds of the polar lights), and Seaquakes. Experimenting with the reverberation of a trumpet sound in the cavernous hold of an iron freight boat, for example, is the kind of experience that touches him deeply, having perhaps a similar effect to that of sacred music of another era blasting through organ stops to fill cathedral vaults.

His quest for unlimited control and modulation of his totems has a Faustian vibe. On the one hand, he wants a finesse and power beyond human capacity; on the other, it’s nature’s heartbeat and breath that inspires him—all reasons to barter with a Mephistopheles, in search of a new musical idea.

Raw materials

“The more limited the means, the more powerful the expression.”—Pierre Soulages.

This quote from the famous contemporary French artist is an ideal for Jean-François Laporte, and he actively applies the notion in his own work by reducing his instruments to the simplest principals: air vibrating a latex membrane, percussive tapping, timbre exploration, arrangement variety, and modulation within narrow limitations.

“It’s very easy to appear complicated,” he notes. “Just put lots of different things together. It’s more challenging to find richness in simple materials and processes. That’s what I am interested in.”

Laporte’s youth afforded him an extensive manual-work experience, whose importance he readily acknowledges. “We built houses from beginning to end, excavating the hole and setting foundations to installing doorknobs. Everything.” Although he insists he is not a tinkerer, he builds his instruments and installations himself as much as possible: cutting, shaping, connecting, wiring, fitting, and plumbing the parts. He says it’s the only way to really know how things work—and knowing is his absolute quest.

The ongoing elaboration of his instruments reveals a systematic approach. As totems, they are emblematic of what Laporte has discovered about sound. Still, he insists he operates by intuition and instinct. As multi-pitched droning fills the studio, he observes his totems with an innocence that makes one believe that their voices are totally new to him, though he has spent the last twenty years teaching them to sing. It is not surprising then, that the intellectualism and abstractions dominating much of contemporary music alienate him and further provoke him to shift his focus from the musical to the visual arts world. Classes with Quebec teacher and musician Marcelle Dechênes were an essential influence in his formation as an artist and composer.

“Aesthetic preoccupation was primary in her approach. In a way, we worked on everything but the music itself. In composition, her attitude was to listen, and talk afterwards. We didn’t intellectualize the music first. That was important to me. However, we did discuss things like the title, the lights, the placement of musicians, the whys and wheres of the piece, but not the form, structure, or articulation.” Dechênes deeply influenced Laporte and this underscores his reticence with regard to his two-year stint in Paris. “At IRCAM, we only talked about structure and articulation. That seemed elementary to me, not part of an art that is advanced or refined. IRCAM made it impossible to ask any of the ‘why’ questions or to have fundamental exchanges between people. Any discussion of aesthetics or ethics was totally removed from creation.” From the outset, his hands-on approach was perhaps a mismatch for IRCAM.

Laporte cites the example of Mauricio Kagel, an innovator who wasn’t taken very seriously, but whose influence, in the end, has been considerable. One finds within Laporte’s comment an insistence on having his work recognized in professional circles and heard by a large public.

Composing

Laporte also writes unconventional music for conventional ensembles: a sixty-minute 2013 commission for Montreal’s Transmission Ensemble, solo instruments, string trios, Quasar Saxophone Quartet, and others, including pieces for grain silos and train and boat sirens. Recent performances of his pieces include a 2011 Venice Biennale presentation. He creates extensively for contemporary dance and performance art, including intimate sound-movement collaboration duets. A new dance-sound piece with Frederic Tavernini will première in Montreal in January 2013, and another with Barbara Surreau the same year in France.

In hopes of assuring optimum performance conditions, Laporte is increasingly selective about commissions. “Having your music played badly is the worst thing possible. Contemporary ensembles don’t take the time necessary to rehearse pieces. Many composers seem to adapt to the situation by writing music that doesn’t need to be rehearsed much.”

Transmission is asking for a full-evening piece that “grooves.” Laporte begins by asking what that means for them. While observing the micro-movements of his latest totem, Vibes, perched in the corners of his studio as it responds to Max/MSP tuning commands, he says he appreciates the limitations of scoring for traditional instruments. Perhaps at that moment he is already thinking about what he will write for a contemporary sextet, while contemplating his latest invented wind instruments. One senses a freshness that will allow him to compose for a piano as if it were just another totem, a history-free invention that makes shapeable sounds.

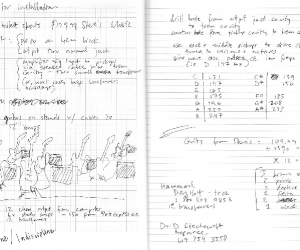

“Commissions are a way to survive,” he notes candidly. He cites his admiration for the music of Ligeti and Stockhausen and states that two-hundred years of purifying the sound that Western instruments make with tonal music has erased the variety of timbre possibilities. “Nothing really new has been done in music since electroacoustic exploration. That gave us a new sound colour at the time . . . but what you experience with your computer? My idea is to look for those sounds acoustically. Acoustic sounds permit reverberation and are propagated in space in a way that electroacoustic sounds are not. You have to enter into a sound’s duration to enjoy and perceive it. If you work in the hold of a boat or in a silo, you acquire a true physical experience, one that affects your vision of the world.” His scores reveal intense visual figurations of what he wants to hear. His goal is to provoke vibrating experiences by sculpting sound.

Performing, a love supreme

“I consider myself a researcher even more than an artist.” This declaration merits consideration and perhaps best illustrates why looking for his grand oeuvre is a misguided way of trying to appreciate his efforts. Laporte is a keen performer, a place where the personas of artist and researcher adhere perfectly.

It already seems ages ago, but it is a month before the end of the millennium, November 1999, and fears of massive information-systems dysfunction and breakdown are being forecast for day one of 2000. Around this same time, in a dimly lit, intimate Montreal performance hall where he has been offered a carte-blanche series, Jean-François Laporte takes a laboured first step towards the audience. Clad only in briefs, he supports a massive wooden frame harnessed to his shoulders. His shaved head exceeds the frame’s interstices; arms, cross-like, support one of the horizontal beams. More than fifty circular metal saw blades dangle freely from the frame, close to his skin, their sway and swivel catching flecks of stage light. The slightest alteration of Laporte’s balancing act, each step forward, sends the sharp metal teeth on a collision course towards each other. The performance is called the Way of The Cross, and the video recording of it shows the magic and drama of the performance. Ordinary notions of time are obliterated as the composer-performer traces his path across a stage that appears as a black square of infinity. Chiming marks Laporte’s steps, a tolling every bit as powerful and haunting eleven years later as at the moment it first rang out. Laporte makes dangerous and delicate music here, playing attentively, endangering his flesh, transporting sound, and bearing its weight like there’s no tomorrow. Only the present exists, and the audience is witness to a rare moment when metaphor, object, and realization are in absolute unity. One Montreal critic wrote, “Laporte possesses that gift of transforming what he hears into a poem, of blossoming his imagination into unsuspected sound bouquets.” Another spectator commented that his Way of The Cross traced a border for contemporary music at the end of one millennium and at the starting edge of another. The high pitch of flashing, metal saw blades dinging into the future left a mark on those who witnessed it.

Laporte is perhaps at his most powerful when performing on his instruments. Shaman, inventor, intense scientist, shop-guy, and seducer all fold into one persona on these occasions. It is perhaps regrettable that the robotization of his instruments will diminish his role as player and effectively eliminate an obvious human presence.

Performances are constructed live. Laporte, however, admits his discomfort with improvisation defined primarily by spontaneity and constant invention. It is interesting that his highest admiration for a performer-musician goes to one who set the mark for improvisation that is still an artistic icon for many musicians. “Nothing comes close to Coltrane.” He shakes his head. “Mastery, talent, expression, inspiration are totally united. It must be the purest joy and freedom to make that music.” Laporte’s tu-yos, khrônos, and vibes don’t immediately sound anything like Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, but Laporte’s intense quest, total engagement, and artistic risk allow a comparison. “The individual on stage in front of the pubic . . . there is nothing as demanding as performing alone for an audience. It takes nerve. You never feel that with a computer.”

He performed solo in Montreal recently with a rope and a tin can at the Opus Music Awards Gala, swinging his flying can, a vintage instrument made from a ventilated tin can attached to the end of a knotted cord. When skilfully guided, it creates a spectrum of haunting sounds that are sculpted, turbine-like, by varying speed and direction. Many in the audience had never heard the piece before, though it comes from his work from “the last century.” Laporte twirled alone at the centre of the singing arc, holding the rope end and casting for the exact timbre.

Kill the concert: installations

A singular creator in every sense of the word, Laporte is not alone on an international hybrid scene that integrates sound art, musical composition, performance, installation, and digital art. He readily cites artists whose work he admires and studies carefully, including Quebecker Jean-Pierre Gauthier, with whom sound is a commonality, and international heavyweights such as Anish Kapoor, Richard Serra—with his astounding simplicity and tactile relationship to raw materials—the kinetic sculptures of Theo Jensen; James Turrell’s work with light, Andy Goldsworthy, the brute force of Anselm Kiefer, and the quirky, hip installations of Zimoun.

His move toward installation is directly related to the perceived limitations in the musical world. “Music doesn’t take humans into account,” he states. “From the word go, visual art does, and it is more open to new experiences.” He perceives the omnipresence of video during contemporary concerts as a sign of desperation. Crossing borders to visual arts might be providing him with a broader view now—but for how long?

Akin, on some levels, to the exclusive group of contemporary creators mentioned above, Laporte combines elements in his own totems. He asks, “What is an installation?” and thrives on the stimulation produced by searching for an answer. He considers diving into formal visual arts studies to inform his quest.

Still hungry for the “big show,” Laporte’s Contemporary Totems produces snappy media documents with attractive images and brief descriptions of his process. In the images’ gorgeous warm light, spectators are pictured as being drawn to the sound-making and its visual phenomena. “I’ve never had a problem engaging my audiences. Young, old, and neophyte, they are always interested and want to come closer.” Indeed, he has intrigue and fascination in his back pocket, know-how at the tip of his fingers. His comment, “I consider myself a researcher more than an artist,” echoes significantly when you listen closely, somewhere in the micro-spaces of his vibrating chord drones. He is also a seducer. The installation-and-visual-arts world might deflate the pestering question of “serious music or not” as fast as a pricked balloon.

Close your eyes for a moment. Forget the tubes, the latex membranes that look like fiery planets. What does it sound like? One gets the distinct feeling of listening to the humming parts of a recycled, post-industrial world, refitted for our curiosity and listening pleasure. Perhaps Faust, loose in abandoned warehouses and factories? Maybe nature’s forces reclaiming our rusty primal pulse?

Orchestra-totem-futures

Laporte dreams of a wall that vibrates. Sketches of a new project show a seventeen-metre metal labyrinth that you can enter to listen and watch. Its working title is Spiral. Plans are in the works for a choir of flying cans (Orbites) whose disc-like bottoms project the faces of spectators. Vibes, the current project nearest to completion, has an inner ear made of a tiny microphone that replaces Laporte as the first listener and feeds information about pitch to a computer program that responds by commanding adjustments in the resonating lengths of plastic tubes. The current touring project, Rust, combines invented acoustic instruments in duo with the electronic instruments of Benjamin Thigpen.

The years 2012 and 2013 are already fully booked with scoring, performing, teaching, and animating his Contemporary Totems studio, where he invites public and artists for a variety of regular activities.

What does he imagine for the future from the heights of the Contemporary Totems? A chamber orchestra of his invented instruments at the disposal of composers, musicians, researchers, and multidisciplinary artists. Composers are already invited to make music with his instruments in a seasonal studio project called Totem Invitation during the first week of June each year. “It forces composers to work with instruments they don’t know.” So far, no one has refused his invitation.

Is a magnificent totem opera or symphony imaginable, or is that beside the point? The onus might be on other composers. If he gets his way, a small, robotic chamber orchestra will be permanently installed in a university research centre. It would be an optimal home where you can’t hear the air compressor pumping, and where players and composers can make music while engineers study and experiment. Will it inspire new possibilities or impose crushing limitations?

Jean-François Laporte works with the concrete, seeks the unlimited, and banks on the unpredictable, a Faustian risk that serves to renew music in this young century.

Audio: Le Sang de la Terre (Excerpt, 2003). Composed and performed by Jean-François Laporte. Image: Jean François Laporte pictured with his invented instrument: the tu-yo. Image courtesy of: Galerie Foundry.