Gentle and intense, soothing and exhilarating, traditional Filipino kulintang music provides the kind of richly immersive experience that makes an hour go by in what seems like a minute. The intertwining, hypnotic rhythms of its gongs and drums rise and fall as the players change tempos and improvise together over repeating patterns to create a fascinating, ever-shifting soundscape that hovers tantalizingly between the ancient and the avant-garde.

Orchestral kulintang music has been played for centuries in the southern Philippines, particularly by the Maguindanaon, Maranao, and T’boli peoples. Sometimes accompanied by dance, it has served many purposes: to send signals between villages, to celebrate weddings and homecomings, to heal, and to entertain. Passed down through oral tradition, kulintang music travelled to Canada in the hearts and luggage of Filipino immigrants. Recently, it has sprouted some intriguing new offshoots in Toronto, as musicians interested in connecting with their Filipino roots combine the traditional gongs with guitars, keyboards, vocals, and even hip-hop beats.

The seven-woman ensemble Pantayo, the spoken-word artist Luyos MC, and the rapper HanHan have all incorporated kulintang into their contemporary music—or their contemporary music into kulintang—and are producing their own remarkable hybrids. Ensconced in Toronto’s close-knit Filipino-Canadian musical community, they share a reverence for kulintang—not just because of its beauty, but also because they see it as a true representation of precolonial Filipino culture. While their paths frequently intersect, these musicians have different ways of working with kulintang, and sometimes play to different audiences.

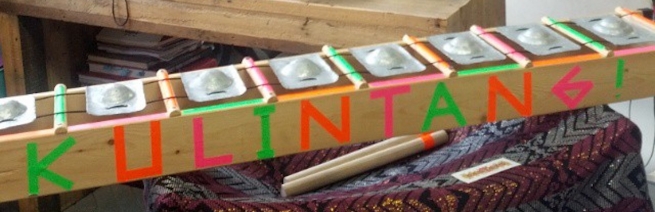

The word kulintang refers to both a style of music and the main instrument it’s played on: a set of eight bossed (or knobbed) gongs suspended on a cord, laid on a wooden rack that serves as a resonator, and struck with wooden beaters. That set is often accompanied by other gongs—a larger one called an agung, hanging ones called gandingan, and a small one called a babendir—as well as a drum called a dabakan. There’s no set tuning for the gongs, which have their own timbres and pitch levels. There are prescribed rhythms for the gongs, and these form rhythmic modes over which the player improvises.

Loosely related to other gong-chime music in Southeast Asia—like gamelan in Indonesia and piphat in Laos, Thailand, and Cambodia—kulintang predates the arrival of Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, and Christianity in the Philippines, and has endured despite the many occupations the country has experienced. The impacts of Spanish and American colonialism on Filipino music have been massive, creating guitar-folk and pop sounds that dominate the airwaves and concert stages. But a surge of interest in indigenous Filipino music in both the Philippines and Canada, for both political and musical reasons, has brought kulintang to the forefront in the search for authentic precolonial music in an age of disposable culture.

PANTAYO

Though most members of Pantayo grew up in the Philippines, it was only after immigrating to Canada that they felt the need to connect with their culture through playing kulintang. They found each other, and other members of the Filipino diaspora, through Toronto’s Kapisanan Philippine Centre for Arts & Culture, a creative hub for young Filipinos that offers dance and music workshops and rehearsal and performance spaces.

Pantayo cofounder Christine Balmes of Toronto studied kulintang at the University of Michigan, and upon returning to Toronto formed a band called Santa Guerrilla, which combined the gongs with electronic instruments. Balmes was interested in learning traditional compositions, but she also wanted to explore the playing of her own original kulintang that’s influenced by her identity as a diasporic Filipina living in Canada. She decided to hold a kulintang workshop at Kapisanan, which was attended by Kat and Katrina Estacio, Marianne Rellin, and Michelle Cruz, and in 2012 they formed Pantayo; Joanna Delos Reyes joined a year later, Eirene Cloma in 2015. After searching for kulintang instruments, which aren’t easy to find in Toronto, they began playing together.

“We started on Katrina’s practice gongs, and when we got better, Christine brought in her bigger gongs and we started playing them,” Cloma recalls. “And then we found more instruments in the Philippines and San Francisco.”

They eventually discovered transcriptions made by ethnomusicologists of compositions that described the rhythmic modes using numbers. “They look like tabs,” explains Kat Estacio. “We look at the numbers and go, ‘This part is gongs three to seven and this is gongs four to eight,’ and it makes a pattern. It’s improvisation mixed with a pattern, like an ascending pattern, and then there’s some kind of descending pattern.”

The group spent many hours practising the traditional compositions, getting the rhythms down so they could think about improvising on top. “It’s funny, because we didn’t know it was improvisational when we started,” Estacio says. “The improvisation only happened after we became familiar with the gongs.”

“It was very technical in the beginning, the way we would play,” Cruz agrees. “It was only later that we started to become creative about it.”

“It’s important to note that we’re diasporic and somewhat new to this culture,” Estacio adds. “When we started we were really rigid and played slowly. But when we looked at YouTube videos of kulintang players in the Philippines, we saw that they play really fast.”

As the band members became more comfortable with the gongs, they started to think about integrating them with Western music. “A big part of playing the gongs is your stroking technique,” says Cloma. “It’s the same hand pattern, but you move up and down the gongs. It’s also about learning what groove, tempo, and feeling we want. And we found similarities to other forms of music in the grooves.”

“Once you’ve established the rhythm, you can deviate from it,” explains Estacio. “That’s when we started looking at the structures, and breaking them down. And that’s what we’re working on now: rearranging the traditional songs to incorporate chords and vocals.”

But the first addition was drums. “I was used to hearing cymbals and kick drum, so it felt natural to add them to establish a steady beat and provide the backbone,” Estacio says. “And then we incorporated bass, because we felt a need to fill the lower end, and then some ambient synths and a bass drum.”

The vocals, performed mostly by Cloma and Delos Reyes, came last, and while they’re pop-influenced, they have an echo in kulintang. “Some traditional songs played on the gongs imitate the way people speak or sing,” says Estacio. “So we’re kind of working backwards, looking at the notes on the gongs and using them to create vocals.”

Playing with all those elements requires the band members to be precisely attuned to each other, shifting tempos together seamlessly. “One of the first lessons we had to learn was how to connect with each other,” says Cruz. “The songs end at the same time for each instrument, and each instrument is connected to another instrument. So we have to have that connection.”

That wordless simpatico came gradually, after playing together so intensively. “It takes hours of practising to create a song,” says Cloma. “There are times when we jam for twenty minutes straight, because we’re really feeling the gongs in the room.” That’s not hard to imagine when the repetitive rhythms and drones can induce a trance-like feeling. “There’s something about the frequencies that makes it soothing. You can really feel the gong sound vibrate in your body.”

“I’ve heard it described as a soundbath,” says Estacio. “It kind of engulfs you.”

Pantayo is recording its debut album with producer Alaska B of Yamantaka // Sonic Titan, with whom the band previously worked on the soundtrack for the videogame Severed. For that project they were inspired by the soundtrack for the movie Akira, which features synths arranged in gamelan tuning. “Playing the gongs for as long as we have, we kind of get wrapped up in our own bubble,” Estacio says. “Alaska gives us different ways of thinking about songwriting and arranging. The idea of incorporating gong tunings into guitars and keyboards was our first insight into other ways we could interact with our instruments. You can create so many sounds. If you hit the boss, it’s a different sound than if you hit the face. You need to fall in love with your instrument over and over and find new things about it. We incorporate the traditional stuff and put our own twist on it. That’s been our training, and it’s still evolving.”

Indeed, some of the tracks Pantayo had previously recorded and put on their Bandcamp page are being revamped for the album, with added vocals. “We’re like gong punks,” says Estacio. “We’re interested in so many things; we can’t stick to one genre. We even incorporate some R&B.”

In the meantime, they’ve been blowing away audiences at their mesmerizing live shows and continuing their education in kulintang. “Our deep interest in connecting with something [is what] brought us together,” says Cruz. “But now we’re learning about all the possibilities of what we can create, and it’s vast. There’s so much for us to explore. Because we’re not just a traditional kulintang ensemble. We’re respectful of the music, but we can’t fully be ourselves if we stick to the traditional ways of playing.”

And yet, for Pantayo, kulintang is more than an instrument. “It’s important to talk about cultural appropriation outside of the music, and the presence of the gongs serves that purpose,” Estacio explains. “It doesn’t have to be spoken in words, because it’s a message in itself. That’s why I think it’s important to incorporate traditional songs and not just write music on top of the gongs. We’re not just using the gongs as different instruments, but for everything associated with them.”

The artist Luyos MC has a different approach to kulintang. She has studied and played the gongs intensively, but she recites poetry overtop, and emphasizes social activism. Luyos MC, who is MaryCarl Guiao offstage, grew up in Mississauga, Ontario, and didn’t know about kulintang until she heard American composer and percussionist Susie Ibarra’s music on the campus radio station in Guelph. “That was the first time I heard those indigenous instruments,” she says, “and my first goal was to learn more about them.”

Guiao travelled to San Francisco to pursue studies in Filipino dance and music, and was lucky enough to study there with legendary kulintang master Danongan Kalanduyan—an ethnomusicologist and performer who passed away in 2016, but whose tireless efforts to teach and popularize kulintang have helped it become a bridge of sorts between traditional and modern Filipino culture. Guiaio bought a kulintang set from Kalanduyan and practised with him until she felt it was part of her. “You’re supposed to grow up hearing it all the time, but that didn’t happen,” she says. “So he would just play, and then I would play.”

In Guelph, where she is now based, Guiao started incorporating poetry into her kulintang, and then added bird songs and other nature sounds. “I use those to remind people of nature,” she says. “And I use healing frequencies that correspond to nature sounds. There are certain sonic frequencies that are believed to affect people on a physical level—they’re calming in a healing way. My intention is to create music that’s soothing, but the social mission is number one. And that is to encourage critical thinking about colonialism. I think it’s important to hear perspectives that don’t usually have a platform, and it’s more appealing to people when there’s music behind it.”

A Luyos MC performance begins with traditional kulintang compositions. “I start with that so people can see where it’s coming from, and I talk about my teacher,” she explains. “And then I’ll have a spoken-word piece.” Guiao plays the sarunay practice gongs and also the gandingan. “I bought the wooden version of the gandingan because I like the sound of wood,” she explains. “I don’t really have a structure— if I like a sound, I’ll play it. I’ve been doing beatboxing. Things come spontaneously, and I’ll add them. I was [recording] a song, and my dog kept barking, but when I listened to it I realized she was in time, so I kept it.”

At a certain point, Luyos MC began adding live sound manipulations and sometimes dancing. “In order to have more things going on without my having to worry about technology, I worked twice with an artist called Dragün,” she says. “There are many elemental sound references that he cued up in one performance he accompanied me on.

“I’d like to collaborate with people who will add layers like electronics and allow me to learn more,” she says. “I don’t want to be a solo performer. I want to collaborate.”

HANHAN

Perhaps the most visible performer of modernized kulintang in Toronto is HanHan—Haniely Pableo in private life—who raps over gongs and hip-hop beats. Pableo learned about kulintang at school in the Philippines. In her hometown of Cebu there was a yearly Mardi Gras celebration with traditional instruments, and “That’s when I was introduced to kulintang,” she recalls. “It’s a weird festival: it celebrates people converting to Catholicism with traditional dances, so it’s tribal music in celebration of colonization.”

Pableo played guitar and wrote poetry, and didn’t become interested in kulintang until she came to Canada and started working as a nurse. “As an immigrant you’re always seeking something,” she explains. “You need something outside of work. I was thinking of joining a choir, but then I met a guy in the library who told me about Kapisanan. I started attending events there, and then I walked into a poetry class.”

She began doing readings, and then spoken-word artist Myk Miranda asked her to perform with him, opening for a band that included her friend from the library, Robert Bolton. He and Alexander Junior were also playing with Christine Balmes in Santa Guerrilla, and they invited Pableo to join that band. “They used gongs with hip-hop, and it was really theatrical, there was dancing and spoken-word poetry and singing,” she says. “So I started rapping and singing backup vocals for Santa Guerrilla.”

Pableo also started learning to play the gongs and performing with Balmes in a duo called Super Inday. “Christine played the kulintang,” she says, “and I would support with a babendir or something.” Eventually Balmes left to form Pantayo, and HanHan began working with Alexander Junior, Romeo Candido, and Rudy Boquilla, who made up the Filipino hip-hop group DATU.

These musicians are part of a tightly knit interlocking circle of Filipino expatriates, all connecting with their roots in their own ways. “Everybody,” Pableo says of the musicians, “knows each other, but everybody has a different focus. Christine was more focused on traditional ways of playing the kulintang.” And HanHan is more focused on live performance with visual elements and lots of collaborators. “I've performed on my own, but it doesn’t feel as good,” she admits. In 2014, she recorded her self-titled album with DATU. “I never intended to make an album,” she says. “During jam sessions we’d create music, and I was satisfied with that. But Alexander Junior kept pushing me because I had so much material. It’s different-sounding, with gongs plus hip-hop. Basically I wanted to show that the new and the old could come together and make something beautiful.”

HanHan’s music combines the gongs with keyboards and infectious dance beats, on top of which she raps in two languages, Tagalog and Cibuano. Her vibrant, high-energy performance on the video for “World Gong Crazy,” backed by DATU and the dance group Hataw, has attracted attention in the Filipino diaspora around the world. “This girl messaged me from Austria!,” she says excitedly. “I got a message from a French DJ who featured my music on his radio show. I thought, ‘Cool! A Tagalog song on French radio!’ And my songs were on an Amazon series called Mad Dogs.”

Future plans for HanHan include a new single in the fall, and contributions to new albums by DATU and the Toronto band Phèdre, which features fellow Filipina April Aliermo. And two of her songs, “Tawa” and “Sige,” were included on a compilation in the U.K. “‘Sige’ was one of the first songs I wrote,” she says. “It was inspired [by my visit to] a live-in caregiver diagnosed with lupus. Nobody was taking care of her, and she was threatened with deportation. My mom was a live-in caregiver, and it resonated with me. Most of my songs are inspired by personal experiences—things I want to say to myself, but in the third person.”

HanHan differs from Pantayo and Luyos MC in that she is addressing Filipinos, with lyrics that most Toronto audiences won’t understand. “If I put something out, I want it to be honest, and you can only be honest if you speak in a language you can fully express yourself in,” she explains. “It's not really for the general Western culture. If they appreciate it, OK; but I want it to be empowering to a new immigrant trying to integrate into the culture. It's not easy, because you always crave that belonging, and sometimes you want to conform and you lose your identity. It’s good that we broke some musical barriers, but I wanted it to be something that someone like me could listen to and think, ‘Yeah, I feel that way too.’ So when I heard the comments from Filipinos all over the world, it made me feel complete.”

Pableo refers to the “World Gong Crazy” video as “basically a culture bomb. Because there’s not a lot of Cibuano rappers out there, especially women. Filipino women are regarded as modest and ladylike. For a Filipina to be rapping [goes] against the grain, and most Filipinas are not as outspoken as me. But sometimes you have to be bravely bad, and break the rules.”

Meanwhile, HanHan is donating proceeds from her album to a school she visited last year that works to preserve indigenous culture in the Philippines. “It’s like a cycle,” she says. “We’re advocating for it here, and going back to preserve it.” Or, as Pantayo’s Estacio puts it, “For diasporic Filipinos, it’s yearning to connect with your culture and finding your own identity, and that looking back to look forward kind of thing.”

Top photo of Pantayo at Wavelength Music Festival by Michael Thomas. Kulintang photo by Christine Balmes, who can be seen below in foreground of Pantayo photo taken at Music Gallery's 2015 X Avant festival (photo by Claire Harvie). Luyos MC photo by Kasia Zygmun. Han Han, performing in "High Blood" at the 2016 SummerWorks festival, with members of DATU and Hataw (photo by Bo Fajardo).