I first saw crys cole perform in a tiny gallery in Winnipeg’s Chinatown. Seated with a contact mike, a pane of glass, and little else, cole reflected the minimalism of her setup in quiet soundscapes and restrained gestures. Immediately, she had the room under her command. There was a charged tension in the air, as if cole was sharing a level of intimacy usually hidden from public view, just by subtly amplifying the movement of these basic tools.

Her calm yet highly concentrated energy is hypnotic, both in live performance and on her rare recordings—though lately her recorded output has increased, with the 2015 release of her debut full-length solo LP Sand / Layna (Black Truffle) and recent collaborations with James Rushford in the duo Ora Clementi and with her partner Oren Ambarchi.

Getting in touch with cole for this article was difficult at times; the globetrotting artist and festival director travelled four continents in only three weeks during our email exchanges earlier this year. Yet it seemed fitting that an artist whose work is determined by space and environment should be occupying so many different countries while we discussed her recent tours, collaborations with musicians such as Ambarchi and Jessika Kenney, gallery installations, intimacy and imperfections, her willingness to fail, and the unique career she’s traced through sound art.

Long before she collaborated with the likes of influential British improvising guitarist Keith Rowe and Japanese guitar improv artist Tetuzi Akiyama, cole was searching for artists who were broadening the definition of what music could be. “As a teenager in Winnipeg in the ’90s it was not terribly easy to get your hands on an array of strange music,” cole says of her early obsession with following sound to its edges. “So I mail-ordered much of it from small labels and distributors. Anything that I could get my hands on that was unusual. I was aware that I was an oddity in my group of friends—I was one of the only women very passionately pursuing more out-there music.” She became fascinated, for example, by “the mysterious and ambiguous quality” of recordings by Andrew McKenzie’s prolific sound-art project The Hafler Trio.

In 1998, cole moved to Montreal and immediately found a home in a supportive and eclectic music community that encouraged her to pursue her own music. After her debut in 2001 in Toronto with Montreal musician Dave Smith, cole began to perform regularly in Montreal at free-improv concerts, though it wasn’t until 2003, after moving to Vancouver, that she began performing solo. Her early contact-mike sets focused on ideas of deep listening, taking both herself and the audience on slow-moving, textural journeys, and carrying what she calls “the energy of self-awareness” out into the atmosphere. While introspective listening environments remain a focus, cole has since expanded the conceptual reach and instrumentation of her sound art—though contact mikes are still a favourite tool.

The rich, textural soundscapes cole creates are not quite sculptural. She prefers to let listeners drift on a timeline, the sounds occupying space as air, unsettled, rather than as matter. For cole, silence is as essential as sound, and often her mastery of negative space is what’s most impressive. She requires of her audience a certain type of silence and stillness; when Sand / Layna—a challenge to minimalism taut with human breath and isolated, coldly manipulated clacks and clamours—mixes with the street noise over my headphones, I’m not sure which is intruding on which.

Organic sound, born of the moment and unrepeatable, is cole’s obsession. She says she never uses sampling or looping, and eschews effects beyond adjusting EQs or adding “a touch of reverb,” preferring the practice of “manipulating materials and playing traditional instruments in unconventional ways.” This pursuit has led cole to build an eclectic toolkit based on the sonic character of individual—and sometimes unusual—items. Aside from her collection of contact mikes, traditional flutes are a current obsession, and she often employs paintbrushes and salt as instruments. Voice, also a more recent inspiration, is something she’s been exploring in depth with Australia-based James Rushford in their touring and recording duo Ora Clementi.

Ora Clementi’s 2014 LP Cover You Will Softer Me (Penultimate Press) requires committed listening. Its immediacy is felt in the artists’ haunting, unrelenting presence, humming, moaning, speaking, and almost singing alone and apart, breathy whispers mingling with sporadic clicks and pops from unknown sources, and tentative, discordant hums. Listeners are summoned to a constantly engaging, sometimes discomforting and at times highly erotic journey, during which familiar sounds are removed from their sources and elevated to emotionally resonant, tenuously controlled compositions which, no matter how mysterious, never depart from earthly known sounds.

Amid all her current exciting collaborations and solo pursuits, she’s found her work with Rushford particularly rewarding. In 2015, the duo played dates together in the U.S., including a performance at Issue Project Room in Brooklyn. In June 2016, the duo played a handful of shows in Europe. This may seem modest, but with her adeptly focused approach, cole views each performance as an opportunity to shed inhibitions and take artistic chances. “I feel eager to take risks, which has always been a part of my work, but with James I feel a great sense of confidence in these risks, and it’s pushed me into territory that continues to surprise me,” she says. “There’s a language and atmosphere that he and I create together.”

Since her teenage days ordering records by mail, cole has been most strongly attracted to risk-taking work, and to musicians who constantly expand and evolve their practices. She considers music a personal and even intimate exchange, and is drawn to vulnerability. “I think that the process of creating should have little to do with the need to define or situate yourself in a broader context, but rather should be about the ideas and the pursuit of a very personal expression . . . I’m most inspired by artists whose work expresses a feeling of exploration and a willingness to fail, creation that is constantly evolving, artists who have created their own distinct languages but are endlessly exploring.”

She has found a like-minded partner in prolific Australian guitarist and musician Oren Ambarchi (see photo below, left), with whom she frequently collaborates in performance and on recordings, notably Sonja Henies Vei 31 (Planam) and Black Plume (Bocian Records). Though they are based on different continents, cole and Ambarchi were constant companions crisscrossing the earth from one engagement to the next during our correspondence this year. Just as cole looks for constant growth from her own performances and collaborations, she also motivates Ambarchi to break out of his own comfort zone.

“She somehow allows me to do things that I wouldn’t do otherwise in a performance context, which is incredibly exciting as an artist,” Ambarchi reveals of cole, in an email exchange. “I’m always interested in going into areas that shouldn’t ‘work,’ and crys allows me to do that . . . it’s had a huge impact on my solo work.” He continues: “We’re reaching for something indefinable, where banal actions coexist with blurry, dreamy sonic textures. When it comes together and works, something personal and uncategorizable takes place. Making our duo record was very uncomfortable at times, yet very satisfying because it was such a challenge. It had plenty of meaning for us and we both pushed each other to explore areas that were quite intimate and personal, yet blurry and ambiguous.”

American composer, singer, and secret punk rocker Jessika Kenney first performed with cole in Melbourne in March 2016, following years of conversation. “I knew it would have intense physicality,” Kenney writes in an email. “We also spent a large portion of our rehearsal time breathing in silence.” Together, cole and Kenney worked out an “alternating dialogue” of each other’s pulses for the March performance. The piece was inspired by the practice of pulse reading in Chinese and Greek medicine, and the intimacy inherent in the detection of one body’s heartbeat by another.“It was quite intense,” cole remembers, “we started listening to each other’s pulses and interpreting what we felt or saw through vocalizations.”

That she would join forces with another artist for the first time and immediately begin feeling her pulse as a means toward a unique performance piece indicates cole’s drive to let personal experiences lead her toward new sonic challenges. Rarely have I met an artist—or a person—as initially guarded as cole, yet as I go further into her work, and as she opens up to me about her practice, I realize this initial reservation is likely born of necessity, a mask for cole’s deep connection to her emotional life. This may also explain why cole favours collaborating in a duo rather than as part of a larger group. In a two-person exchange, a special language between musicians can be invented, she writes: “It’s really just an extension of life to me. You learn about yourself by relating and communicating with others. You maneuver obstacles, solve problems and share blissful moments.” Recently, cole has worked with artists such as Akiyama, Tim Olive (with whom she recorded in Japan in early 2016) and Melbourne-based musician Francis Plagne. She also values highly her intersections with older experimenters and sound artists such as Phill Niblock, Akio Suzuki, Limpe Fuchs, Charlemagne Palestine, Alvin Lucier, John Tilbury, and the late Tony Conrad.

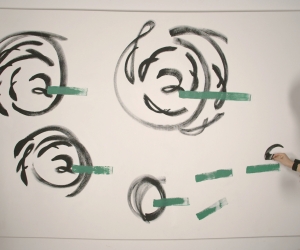

Some of cole’s most stunning works are solo, including her gallery exhibitions, where she has often combined unique instrumentation with mystifying visualizations, such as outfitting a broom with a contact mike before sweeping a warehouse in Sweeper (2009) (video of this performance can be found on Vimeo) and, astoundingly, filling a London UK gallery with 375 kilograms of salt.

In 2013, cole’s site-specific piece filling a space with salt (in two parts) was installed as part of the group show At the Moment of Being Heard, curated by Simon Parris, at the South London Gallery. Four air vents in the corner of one gorgeous, high-ceilinged gallery room captured cole’s imagination. She worked with curator Parris to transform these vents into gravity-powered instruments. Scaffolds were installed, and from them, salt funneled down to mike-outfitted grates and onto sheet metal lying below, which was affixed with two of cole’s signature contact microphones (“EQ’d very differently,” she says). Shotgun microphones also captured the sounds of salt particles as they fell, allowing cole to amplify, in a way, the sound of the room’s empty space as salt piled up below and eventually emerged through the grate in the floor as a slow, mysterious white intruder. She describes the sound of the piece as a “subtle rainfall . . . but as you approached the piece the complex detail and percussive quality of the work really emerged.” The visual experience was also key to cole, who remembers that visitors “could sit and listen while looking across the room at the salt peak.”

Another installation,

38,208 km (the distance required to make this work) [LISTEN NOW, TRACK 6], allowed cole to explore personal narratives. Commissioned for exhibition (in 2014) at the soundart space in Museum Ostwall in Dortmund Germany, the work brings

together material cole created in Brussels, Melbourne, and Winnipeg. The distance between these three locations—as the crow (or a passenger jet) flies—is impressed on the piece’s meaning; the title is both a reference to the places where it was assembled and, cole explains, “a tongue-in-cheek comment on how much ground is covered regularly between my partner and me in order to be together.” So far, most of cole’s installation work has required a performance element, though cole says that that may not always be the case in future. Like cole’s more traditional live shows, these installations rely heavily on an engagement with individual physical spaces.

I ask cole what it’s been like to be so transient of late, especially considering her role as festival director of Send + Receive, Winnipeg’s annual fall festival of sound art and experimental music founded in 1998 by Steve Bates (cole has been director since 2008). “These days I feel like a bit of a vagabond,” she confesses. “I do still call Canada home. My home base, my little nest with all of my things, is in Winnipeg, and my family and some close friends are also there.” Although Melbourne has become her second home, cole finds support from a rich community of sound artists and curators worldwide, and she clearly loves to find herself on the road. “Every place that I spend time offers unique opportunities for my work. The feeling of a place, the geography, the food, the vegetation, the urban layout . . . all of that stuff stimulates me and feeds into my practice.”

For fun, I ask crys cole what’s always in her travel bag. “Slippers that my grandmother knits me, journals, extra hard drives, a zoom recorder, dark chocolate, and as broad a range of variable season clothing as I can cram into one big suitcase,” she reveals. On the topic of contact mikes, she confesses that she always keeps about six or seven on hand: “I would definitely say that I have favourites.”

Top portrait of crys cole in Milan in Summer 2016 by: Oren Ambarchi. Middle photo of Ambarchi and cole performing at VIVO Media Arts Centre in Vancouver in 2015 by: Alisha Weng. Bottom photo of cole with her site-specific sound sculpture filling a space with salt (in two parts): Courtesy of the artist and South London Gallery.