In the 1970s, electronic music studios at the University of Toronto and McGill University sparked exciting ideas in guitar composition. With a focus on the evolution of Canadian works for guitar and electroacoustics, guitarist and composer Amy Brandon tracks key events and works from then to now.

(Check out Amy's SoundCloud playlist at the bottom of the article!)

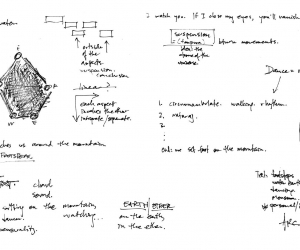

In my work organizing the inaugural 21st Century Guitar conference, held in Ottawa in August 2019, I was surprised to discover how vast the Canadian repertoire is for guitar and electronics. The conference’s marathon of Canadian guitar-and-technology works ran to almost eight hours, with simultaneous concerts taking place in three separate halls. Although more than forty-seven works were performed (many are referred to in this article and its sidebar), this event featured only a small portion of the Canadian repertoire. Certainly the influential spark of the University of Toronto Electronic Music Studios (UTEMS), the McGill University Electronic Music Studio (McGill EMS), and other studios founded in the 1960s, along with the pioneering work of Hugh Le Caine and other founding members of Canada’s electroacoustic music scene, created the foundation for what has become a significant body of work. As well, the trend toward modernity and experimentalism in the Toronto guitar community of the ’70s most likely strengthened national interest in contemporary music for the guitar at a crucial time. Whatever influence these early factors had, the fact remains that the repertoire continues to expand significantly each year, especially through education programs such as the Canadian Music Centre’s annual Class Axe, produced with the Guitar Society of Toronto. Established by guitarist Rob Macdonald, Class Axe boosts the creation of works for electronics and guitar by bringing together guitarist–composer teams, such as Emily Shaw and Christina Volpini (for emily); and An-Laurence Higgins (in photo below) and Kim Farris-Manning (almost touching) in 2019.

early buzz

Listening to Terry Rusling’s four-minute If I Could Find a Thing to Hate for guitar, human voice, and tone signal, it is hard to distinguish the timbre of the guitar from the faint processed tape, analog hum, and eerie sine tones. Completed in 1965 at UTEMS, If I Could Find a Thing to Hate is among the earliest pieces of electronic music incorporating guitar. Other early international guitar-and-electronics works from this period include Peruvian composer César Bolaños’s 1966 Interpolaciones for electric guitar, four-track tape, and six speakers—a metallic mixture of quasi-improvised guitar interruptions, processed electric-guitar sounds and clipped human voices, recorded and performed in South America’s first electroacoustic studio; Japanese composer Kenjiro Ezaki’s 1967 Music for Guitar and Electronic Sound for amplified classical guitar and tape, in which a second set of speakers is positioned behind the guitarist to separate the processed live guitar from the tape (regrettably, the tape for this work is lost, although the score with stage plot remains); U.S.-based Scottish composer Thea Musgrave’s 1969 Soliloquy I for solo classical guitar and tape, composed in renowned electroacoustic pioneer Daphne Oram’s London studio; Eduardo Polonio’s Gaudeamus-nominated work Rabelaisiennes for prepared guitar, electronic filters, and tape; and Eric Salzman’s Nude Paper Sermon for voice, guitar, and electronics (1969); and ensemble works by Feldman, Křenek, Behrman, and Kosugi.

Guitar also shows up in a small way in the instrumentation of large-scale early Canadian electroacoustic works, such as R. Murray Schafer’s Loving (1963–5) and István Anhalt’s pioneering Symphony of Modules (1967), the latter produced at the McGill EMS, which Anhalt founded in 1964 with the assistance of Hugh Le Caine. In these works, guitar is incorporated in the soundscape and instrumentation as source material, or as part of an ensemble, without being featured as a solo instrument. Another work of this nature is Kevin Austin’s fifty-five-minute Piece for Four-Track Tape Recorder Canada Unlimited Number Two–subtitled Sam McGee (1970–73), built on processed recordings of Robert W. Service’s classic Canadian poem “The Cremation of Sam McGee” and integrating an improvising ensemble that includes guitar. This improvising ensemble eventually morphed into the live electroacoustic group MetaMusic (including guitarist-composers Martin Gotfrit and David Lindsay), which disbanded in the late 1970s. Written in 1968, Marcelle Deschênes’s large mixed work Voz (cantate mitrailleuse) includes both acoustic and electric guitars and features texts by Che Guevara and Raôul Duguay, using spatial quadraphonic diffusion of the instrumental and vocal groups within the performance space.

While the thread of guitar does subtly snake through the early Canadian electronic-music scene, the first Canadian works of that sort in which the guitar takes a central role appeared in the early 1970s. Ginette Bellavance’s Match en coordonnées for two percussionists, two electric guitars, and tape was performed in 1975, conducted by Serge Garant, at the famous Nocturnales concerts of the University de Montreal. Sergio Barroso’s Yantra I and Yantra III (1972) were initially written and recorded in Havana, prior to Barroso’s emigration from Cuba to Vancouver: Yantra I is a fascinating listen, a mesmerizing and swirling mixture of recorded and processed, extended classical-guitar techniques, under and overlaying the acoustic performance, creating a dense timbral maze. Yantra III, equally curious and mysterious, begins by layering an excerpt from a well-known work for classical guitar (Canarios by Gaspar Sanz) with processed bell-like harmonics, body-taps, and other clouds of extended guitar techniques.

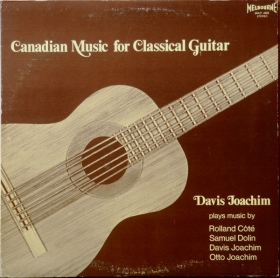

In 1973, composer and McGill professor Otto Joachim wrote Stimulus á Goad for solo guitar and live electronics, for his son, Montreal-based concert guitarist Davis Joachim. Created in Joachim’s private electroacoustic music studio, Stimulus á Goad is both aleatoric and electronic, fitting for a work by a composer credited with writing the first chance music in Canada (Nonet, 1960). The piece uses improvised, extended classical-guitar techniques (as well as, optionally, the guitarist’s voice) to create the electroacoustic soundscape via a microphone feeding into the McGill EMS Synthi VCS 3 synthesizer, whose output then stimulates and goads the performer into certain directions in their improvisation. The score directs the performer to “interfere, or follow the sounds electronically produced.”

Stimulus á Goad marks a moment when the peculiar cross-pollination of Canadian contemporary guitar and electronic music began to expand—first, within the growing experimental classical guitar scene in Toronto of the mid 1970s.

aleatoric adventures

Although much of the early classical guitar activity in Canada, such as concerts, teaching, and performances by visiting artists, had taken place in Montreal, the scene expanded in 1956 with Vienna-born classical guitar Eli Kassner’s establishment of the pioneering Guitar Society of Toronto and, in 1959, of the first university guitar program in Canada, at the University of Toronto, in order to “foster understanding, appreciation and the study of the guitar.” The Guitar Society soon became instrumental in not only promoting the guitar in Canada by organizing master classes and concerts of international stars like Julian Bream, but also by commissioning new works from Canadian composers. One of these first commissions was Harry Somers’s Sonata for Guitar (1959), lightly referred to by the composer in a CBC radio interview as “the sonata for fifty bucks,” which was premiered by Peter Acker in 1964. Many other solo works commissioned by the Guitar Society were modernist, if not avant-garde; notable examples include Francois Morel’s atonal work Me duele España, premiered by Michael Laucke in 1975, Contrasts for guitar by John Wienzweig, premiered by Leo Brouwer in 1978, and John Gordon Armstrong’s Incantations, premiered by Alan Torok and Doug Perry (viola) in 1981.

The Guitar Society also held the first international guitar conference in 1975. The conference programmers strove to represent the instrument’s more traditional European classical and South American voices (with performances by Carlos Barbosa-Lima and Oscar Ghiglia) as well as its contemporary voices. In addition to performances and a composition workshop by composer-guitarist Leo Brouwer, the set piece for the competition was, surprisingly, a contemporary work in free notation, Soring by Gary J. Hayes, commissioned by the Guitar Society of Toronto through the Ontario Arts Council. (The inaugural competition was won by guitarist and future Juilliard faculty member Sharon Isbin.) As Canadian guitarist-composer Robert Bauer said to composer and radio host Norma Beecroft in a 1975 interview on the CBC Radio show Music of Today, Soring was considered avant-garde by most of the competitors, and they had numerous questions for the composer about exactly how it was to be performed. This significant amount of space offered by the Guitar Society of Toronto to contemporary works also extended specifically to pieces for guitar and electronics. At Guitar ’75 Brouwer not only performed a South American work for guitar and tape, he also conducted a projected graphic score for large guitar-ensemble by composer Udo Kasemets, Guitarmusic for John Cage (1975), another Guitar Society of Toronto commission. At the conference, guitarist Davis Joachim performed a program of Canadian experimental works, which included his father’s Stimulus á Goad. Canadian guitarist-composer William Beauvais, present at the conference, wrote in a 2012 blog post that Brouwer “had played a headlining concert a couple of nights before and the second half of his program had consisted of modern South American works. For the first time I saw a guitarist work with a [reel to reel] tape recorder, and it was also my first time seeing a guitarist play aleatoric music.”

In 1978, the Guitar Society held its second conference, which included a composition competition called Quest for New Music. Of the startling seventy-five entries, three were chosen as winners, including a work for guitar and tape created at UTEMS in 1976, Interaction by Tomas Dusatko. This connection back to one of the origin points of Canadian electroacoustic music is significant. After all, UTEMS was the second electronic music studio established in North America, closely following the creation of the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center. As many alumni have noted, UTEMS—which was founded by Dr. Arnold Walter, along with technical advisor Hugh Le Caine, and faculty members Harvey Olnick and Myron Schaeffer—paved a vast highway for the Canadian electroacoustic music community, and was also a locus of significant international electroacoustic work by figures including Milton Babbitt, Pauline Oliveros, and Mario Davidovsky. Since Hugh Le Caine’s Dripsody in 1955, Canadians such as Barry Truax, Ann Southam, Gustav Ciamaga, and many others have been pioneers in the creation of electroacoustic music, equipment, and techniques, and the UTEMS studio in Toronto was naturally hugely influential for several generations of established and emerging Canadian and international composers.

This emergence of Toronto as an international centre of both electroacoustic music and contemporary guitar may have exerted some influence on guitarists and composers who were active in that early period. Toronto-based composers with connections to UTEMS and Guitar ’75 wrote several works for guitar and electronics during the same period. One such composer was Robert Bauer, who commissioned a guitar duo and electronics work from David Jaeger, Quanza Dueto (1975), and wrote several pieces for guitar and electronics himself, including Nondescript (1975), Concerto for Viola (1975), and Suspended and Mobile (1982), for all of which the electronic parts were composed in his Ottawa home studio. For Extensions II (Guitar) (1974), a tape work, Bauer created guitar sounds at UTEMS using a detuned classical guitar augmented with paper clips and pipe cleaners and using other extended techniques; Bauer’s guitar source-material was used by Robert Daigneault for his 1975 tape work Guitar Collage. In 1975 Bauer and Daigneault released the album Guitar Extensions, which consisted exclusively of works for contemporary guitar and guitar and electronics pieces. In a wide-ranging interview with Norma Beecroft, for her three-part series on contemporary guitar for Music of Today, Bauer specifically mentioned UTEMS as his introduction to electroacoustic music, as he had not received that training elsewhere. In her introduction, Beecroft, herself a celebrated electroacoustic composer and a noted historian of international electroacoustic music, said that “Canadians very well might be taking the lead” in spearheading contemporary music for the guitar, which she colourfully described as “an inexhaustible source of wild music.”

From the late 1970s onwards, there has been a modest but steady proliferation of Canadian works for guitar and technology. Composers based in Western Canada, or who wrote notable early works while based there, include R. Murray Schafer (whose Le Cri de Merlin was premiered in Toronto by Norbert Kraft at Guitar ’87), Stephen Chatman, Jon Siddall, and John Oliver, a founding member of McGill EMS’s live electronics ensemble Group of the Electronic Music Studio. [See West Coast section of the sidebar in the print edition of this article for a select list of composers and works.]

Notable works from Quebec composers include McGill EMS director alcides lanza’s ’80s series for guitar and electronics, Módulos II, Módulos III, and Módulos IV, and John Rea’s Com-possession ( … daemonic afterimages in the theatre of transitory states), which won the Canada Council for the Arts’ prestigious Jules Léger Prize for Chamber Music in 1981. Montreal guitarist-composer Tim Brady is well known for his multidecade career of composing, performing, and organizing numerous innovative guitar-centred works, including pieces for solo guitar and electronics. In Atlantic Canada, composer Derek Charke has frequently composed for guitar and electronics, in particular for his duo with concert guitarist and fellow Acadia University faculty member Eugene Cormier.

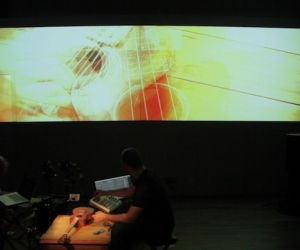

next frets

In the years following the Guitar Society’s conferences, Montreal and Toronto remained the more active scenes in terms of presenting new works for guitar and electronics. From 1987 to 1995, concerts programmed by the Canadian Electronic Ensemble—which was founded in 1971 by UTEMS members David Jaeger, Larry Lake, David Grimes, and Jim Montgomery—premiered numerous guitar-centric works in a series of six guitar-centred concerts called Guitar Boogie. These concerts regularly featured the work of guitarist-composers working with guitar and electronics, including Royal Conservatory of Music electroacoustic studio director Wes Wraggett, Jon Siddall, David Lindsay, Tim Brady, Kristi Allik, William Beauvais, and John Gzowski. In the late 1990s and early 2000s Montreal’s Tim Brady organized several large events focused on the electric guitar, including Guitarévolution in 1997 and 2002 (coproduced by Lauren Pratt), with concerts being held nationwide. Through the early twenty-first century, the guitar and electronics community in Canada continued its growth, with numerous new works emerging from across the country [see sidebar] including and adapting new technologies as they emerged, such as MIDI guitar (John Oliver, Martin Gotfrit), musebots (Arne Eigenfeldt), video games (Michal Seta), and visuals (Kim Farris-Manning, Derek Charke). As the 2019 marathon concert at the 21st Century Guitar conference demonstrated, the steady stream of Canadian works for guitar and electronics is still flowing strong.