There’s a faint but persistent ringing coming from the southwest corner of Ayelet Rose Gottlieb’s Vancouver apartment. We discover one of her young twins picking purposefully at the keys of a brightly coloured toy piano. The other twin comes over, attracted by this large stranger’s curiosity, and contributes her own jangling notes. When I start playing complementary sounds on Gottlieb’s nearby upright, the toddlers move closer and reach up, way up, to the big adult keys. I hadn’t intended to start our interview with a trio performance, but it was hard to resist.

It’s easy to imagine the Jerusalem-born Gottlieb growing up in a similarly comfortable, cluttered, and musical environment. Her father and his brother played guitar; their father was an adept clarinet player. Her maternal grandfather was content to play the radio, but his favourite airwaves carried music that would not have been heard on the paternal Swiss side of the family. “He was born in Palestine, and I always think of him as a Palestinian Jew, because his Arabic was just as good as his Hebrew, and he worked primarily with Arabs. He was a carpenter,” Gottlieb says with affection. “I got to hear a lot of Arabic and Middle Eastern music through him—and, parallel to that, Western classical music and jazz from my dad’s record collection, and a lot of ’70s rock and pop from my uncle’s collection, which I inherited when he moved to Australia. He gave me all his albums—about a thousand albums. So I got to hear a huge variety of music growing up.”

Not surprisingly, Gottlieb’s own music is sonically and culturally diverse. She can sing jazz standards one moment, and move without strain to free improvisation the next; her New York City-based vocal quartet, Mycale, switches seamlessly from Berber to Portuguese to Hebrew; and she consciously combines Arab and Eastern European motifs on her beautiful album of self-composed art songs, Roadsides (2015).

Israel, where she still performs occasionally, offered Gottlieb a worldly musical education long before she left home to study under pianist Ran Blake and others at Boston’s New England Conservatory. One lasting source of inspiration was former Doc Severinsen sideman Arnie Lawrence, who founded Jerusalem’s International Center for Creative Music. “He was a saxophone player who was on The Tonight Show way, way back, so he played with everyone from Liza Minnelli to Dizzy Gillespie,” Gottlieb says. “He moved to Israel before the wall was built. I was sixteen or seventeen, so it was just the right timing for me—and I think a lot of what you find now, globally, with Israeli jazz musicians comes from him.

“He would take us teenagers to Ramallah, to the West Bank, to play with Palestinian musicians and kind of exchange culture through jazz, through playing standards. He was all about soul, on every level imaginable, and that’s what he taught us.”

At the same time, Gottlieb was developing an interest in more open-ended forms, primarily in response to what she describes as “a primal need” in her own soul. “I played classical flute until the end of high school. When I was about fourteen, one of my closest friends was a dancer, and we would improvise together,” she explains. “I would improvise on the flute, and she would improvise with dance. I didn’t even know to call it improvisation—I just played, and she did whatever, and we kind of inspired each other. And after that I became good friends with a wonderful singer, Julia Feldman, who still works as a jazz singer in Israel. We would compose together, but the forms and structures that we would create were always quite abstract and quite broad. Again, we didn’t know what to name it, because school was more classically oriented. If it was jazz, it was more blues or traditional jazz. Nobody ever spoke to us about Ornette [Coleman] and so on.”

Music school gave Gottlieb the names and theories that she needed to complete her education, but her studies obviously didn’t inhibit the creative impulse. Even today, she says, she doesn’t have one particular method of working, other than that almost everything she does stems from the near constant flow of sound that runs through her waking mind.

“Usually what happens is that the music forms in my head first,” she elaborates. “And then I need to transcribe it from my head for instruments, through the piano or whatever. And then once it’s on the page I reconsider every note and reconsider every choice, and sometimes I change it and sometimes I don’t. But the first and most significant work, I do on my own without paper, without anything—just in my head. That’s also how I judge ideas: if something lingers and I keep coming back to it and keep thinking about it and it keeps developing, then I will take the time to write it out. Often there are ideas that float by—like, ‘Oh, that’s a nice line!’—and I’ll just let it go if it’s not something that stays with me.”

Indelible memories can also result in enduring melodies, as is the case with Shiv’a, Gottlieb’s newest album, released February 2016 on the New York and Chicago-based label 482music. Scored for the ETHEL string quartet, plus percussionist Satoshi Takeishi, pianist Anat Fort, contrabassist Sean Conly and Gottlieb’s own voice, the wordless undertaking is a powerful evocation of loss. “I didn’t feel that I wanted to use words,” Gottlieb says of the album, which is available only on LP or as a download. “I felt like I had questions in sound.”

The record was inspired by the almost simultaneous deaths of three friends and by the Jewish and Buddhist mourning rituals that helped ease her heartbreak. “First of all, shiv’a. It means seven in Hebrew, and it’s also the name of the ritual that a family does after death: when a family member dies you sit at home for seven days. Usually you sit on the ground, and you just take that time to reflect. And for me, in general, I find ritual to be a very powerful thing, and I think it’s a very important thing for people to experience. It puts a barrier inside the lineage of time, and allows you to really take a moment to understand a shift. I like that concept of taking a full week to kind of stop your world and not just go on with your business, and really reflect on what happened.

“One of my friends who died was the percussionist and drummer Take Toriyama, who recorded with me on some of my albums, and played with me for about five years,” she continues. “He unfortunately committed suicide, and his girlfriend told me that after his death she walked around with his bells in her backpack. She also told me that there is a Buddhist belief that the spirit lingers in the world for forty-nine days after death before it continues on. So that also has seven inside it—seven times seven being forty-nine—so I asked a friend, the artist Michelle Jaffé, to make an instrument out of forty-nine bells that I collected from different parts of the world, and she made this structure with the forty-nine bells that is played throughout the piece. So from the beginning I knew that Shiv’a was going to be in seven movements, and that it was going to have those bells as kind of a carry-through.”

Shiv’a was partially written in New Zealand, where Gottlieb’s husband was working on contract as an animator. “I had long stretches of time there, just sitting by the ocean, meditating, and writing music,” she says. His work is what brought the peripatetic singer to another oceanside location, Vancouver, where she’s been delighted by the local music community.

“I’ve found very open people, both musicians and audiences,” she says. “Whether I’m doing very avant-garde stuff or through-composed music or whatever it is, it seems the audience is always very open to receiving it, and there’s not much preconception about what’s good or bad in music. People are coming in with open hearts to make the music and to hear the music, and I really appreciate that.”

One luxury she’s not getting on the West Coast, however, is much opportunity to bliss out by the sea. For one thing, those twins have come along; and, at the time of our conversation she was eight months pregnant with her third child. [Ed.’s note: Gottlieb gave birth to a healthy baby in December 2015.] As any parent knows, contemplative time is a scarce commodity during those early years, but that doesn’t keep Gottlieb from continuing to muse about the nature of sound.

“It’s interesting to think about how important music is as a human experience, especially now that I see my kids, who are so small, getting involved with it,” she says. “They still don’t understand language, but music is an immediate communicator, even more than movement. My boy is now attached to Haydn’s Trumpet Concerto. He says ‘Pum pum pum? Pum pum pum?’ and it means he wants to hear that piece. And when it comes on, he’s so excited that he’ll dance to it. I see it elevating him, and yet it has no content beyond the fact that he knows it, and something about it resonates with him. It’s pretty phenomenal.”

FYI (Updated May 10, 2021): Ayelet Rose Gottlieb performs at the 2021 Festival International de Musique Actuelle de Victoriaville (FIMAV) at 5:30 p.m. on Friday, May 21, 2021 in Carré 150, Victoriaville, Quebec.

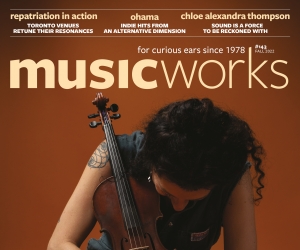

Photo of Ayelet Rose Gottlieb by Bentley Wong.