“My work is what it is and I move in many worlds. I would have nothing

except for being carried on the shoulders of friendship and shared interest.”

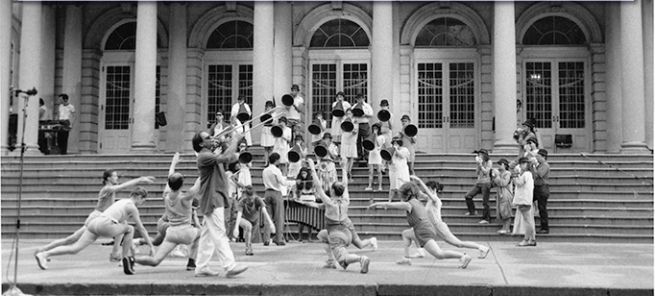

Intrepid sonic investigator Charlie Morrow’s early-’90s Lower East Side event, Urban Jungle, spilled out way beyond the confines of the Sareido Gallery on West Broadway, mushrooming into a happening—and traffic hazard. My sole instruction had been to ad lib a “sub Marcel Marceau floating in slo-mo in an aquarium” in the gallery’s front window. I got easily swept up in the fanfare. This multisensory event of purposeful mayhem was nothing if not a noble attempt to jam with our environment, come to terms with it by recycling what we unconsciously absorb in the urban jungle every day.

As John Lee Hooker put it: “It’s in him and it’s got to come out.”

Some implode in this chaos, others thrive. Morrow thrives. The fact that his signature bowler hat, inherited from his father, stays atop his head is a good sign. I see it as a symbol of equilibrium. Enhanced chaos must, however, serve as choreography for Morrow to allow one and all to mimic and plug back into our tumultuous surroundings. Going with the flow but never drowning in the undertow.

I was less fascinated by Urban Jungle’s mixed results than by how and why Morrow, a self-described “ceremonial musician / event-maker,” negotiates that fluid passage between the public taken up by the private and the private incursion into the public, and is able to pass effortlessly through the barriers that separate the two spheres while fostering a symbiotic, revealing, joyous interplay.

Entering the crowded fray with assorted soundmakers can serve as a patch, a leap of voltage across synapses, an instant of forgiving and renovation. Ever the ambassador, Morrow urges a path littered with liaisons as our best bet for survival. But why?

I thought a profile of Morrow was in order, what with our reconnection twenty-five years downstream and—me being a fan of his 2011 three-CD retrospective Toot!—with the 2018 release of Toot! Too, a double CD full of sound-strategy works that encourage dialogues between participant and spectator, spectacle as playground, everyday life as stage. And, of course, the fact that he has collaborated with a sprawling constellation of twentieth-century giants, including Don Cherry, Jerome Rothenberg, Allen Ginsberg, Joan LaBarbara, John Cage, Nam June Paik, Alison Knowles, Charlotte Moorman, Yoko Ono, Simon & Garfunkel, and Andy Warhol—among others.

BIRTH OF THE CLUES

Charlie Morrow’s story begins at birth, a cliché for some, but for him a dearly held fact, because his memories of his birth catapulted him into art. He spent over a decade recalling the “physically painful passage through maternal contractions and expulsion into the aerobic world,” he writes in our recent email correspondence. “My involuntary attention to sound begins at gestation: Flash. When that fetal me picked up sound and processed it, captured by it as I am captured in this human form. As I write, my mind zooms back to those first moments.”

There are many who have recounted prebirth memories. Author Ray Bradbury claimed to have total recall. Salvador Dali described intrauterine life as paradise. But few have drawn as much inspiration from that moment as Morrow. Like feet to a diving board.

“Using that memory as a lever, I found a memory trail into my first awarenesses,” he muses. “I heard and recalled sounds of the outer world through my mother’s body. Dream Chanting evolved from that.” The sounds of a “parading military band, sound inside and out of the body” fostered his early fascination with brass instruments.

At age eleven, he became an official bugler at a Boy Scouts camp. “I would bugle at wonderful hourly times like sunrise, mess call, taking the flag down. There was a metal megaphone suspended from a frame on a hill overlooking the camp in three areas. I got to play the calls three times, once in each area’s direction. The resonance of each direction was particular, unique.”

It’s rare to remember one’s birth, but even rarer to know one is predestined to become an artist. It is no stretch to say that Morrow has been an artist all his life—even when he wasn’t yet a practising one. “Mother used to say the train went ‘choo choo bringing daddy home from the war’ . . . The high-tension wires went ‘oooo oooo, don’t touch me, I’ll shock you.’”

He has always sought the sounds that link the forces and stages of his life together. Life, for Morrow, is an investigation of how sound can offer meaning. More precisely, there is no separation between art and life. Perhaps something like what Albert Camus once said: “The only way to deal with an unfree world is to become so absolutely free that your very existence is an act of rebellion.”

By age six, when most of us are preoccupied by toys and candy, Morrow was already taking piano lessons and writing “little tunes” in small, wire-bound, music notebooks. “I loved to stretch out musically on the piano, to improvise. It put me in touch with a flow which I have returned to ever since.” His fascination with projecting sound beyond the self into the imaginal infinite led him to the magic of radio. “My activities as a ham radio operator, circuit bender, and antenna builder opened parallel universes,” he notes in one of our extensive conversations. “I taught myself Morse code, FCC rules, and electronics. The airwaves extended my sense of multiple universes: on-air connections to people around the globe contrasted with the small events of my personal life in Passaic, New Jersey.

“I was asthmatic and playing the trumpet allowed me to feel normal,” he explains in the Toot! Too liner notes, “It led me to many new places—the trumpet, radios and electronics—and it allowed my insides to feel okay. Remember, too, that I was coming out of a home with two psychiatrists, and healing was a way of life.”

Morrow eventually drifted from piano to trumpet, bugle, and voice. The exploration of his voice led to breath-and-chant healing ceremonies; soundmaking as a link between us and them. “When I met my second trumpet teacher, cornet soloist Sam Martinique, doors opened. He tied a trumpet with a rope to a water pipe in his basement. It balanced in perfect trumpet horizontality. Sam walked up to it with his hands to his sides, put his lips to the mouthpiece and blew a triple high C. Sam’s pressureless trumpet method stays with me to this day. I have ever since applied the learned breath-control to jaw harp, shells, shofar, alphorn, neverlur [a valveless brass instrument], blades of grass . . .”

BREAKING OUT

I know many unique people, but few as unique as Charlie Morrow, who was born in 1942 in Newark, New Jersey. More than sixty years of interactive projects have cast him deep into other realms, uncovering new opportunities for art strategies that stimulate communication between the in-here and the out-there. As a DIY-conceptualist-doer, audio-artist, composer-collagist-performer, and provocateur, he walks a wobbly tightrope between grandly sprawling spectacles and intimately clandestine (sometimes barely audible) events.

As an avant-gardist, his conceptual antics are often likened to Fluxus, although many of his works predate that 1960s movement by several years. Morrow was already an artist in his early teens; by the mid ’50s, he was going joyously astray, creating conceptual, spatial, and humorous music that would reveal a particular sophistication, depth, and humour. He studied classical-music composition in a sterile environment, but eventually grew restless with all that rote replication of dead genius-composers.

He composed a series of mature, Dada-informed, Fluxus-like works avant la letter. Very Slow Gabrieli (1957) is a Satie-ish slow-motion performance of the 1597 Giovanni Gabrieli composition “Sonata pian’ e forte” that stretches the work by slowing it to one fifth of the original tempo, which was further enhanced by the performers’ slo-mo physical gestures—a pretty intrepid leap beyond what is expected of a classically trained teen.

At fifteen, he was already introducing chance, surprise, interruption, odd metre, and humour into his compositions. His 1957 satirical piece Interruption Music (unknown to the conductor . . .) requires orchestra members to stop, cough, and scratch themselves at prescribed times to surprise the conductor. Written the same year, his Cagean Psychic Music for Concert Band (no audible music) instructed musicians to project their music mentally as they silently mimed the performance.

But it was in the heady ’60s, with the emergence of pioneering movements like Fluxus, happenings, postclassical-exploratory-environmental, free jazz, experimental rock ’n’ roll, political turmoil, and new electronic technology that he found purpose and could properly proclaim: If this is art, then I am an artist.

The ’60s offered an escape hatch into far-flung territories beyond the rusty classical gates. Out there he found an exciting new world: commercial, pop, electroacoustic soundscape, duetting with nature, sound-space realignments, ambient installations, and more.

His musical production auspiciously entered the pop-music world at college, where he met Art Garfunkel, and ended up advising Simon and Garfunkel on arrangements for their Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme, adding bells, strings, and a Renaissance keyboard on a few tracks. This led to work with other bands, including the Rascals: creating “Groovin—Do You Feel It, A Fantasie” for orchestra and rock band, performed at the Garden State Arena, and producing and arranging “Look Around” and the modest hit “A Ray of Hope,” for their ambitious, symphonic double album Freedom Suite (1968).

He so enjoyed working in a studio that he built his own and ventured into sonic experimentation. His first multitrack recording was long-time collaborator Jerome Rothenberg’s translation of Frank Mitchell’s “Horse Song #12.” This led to recordings of Jackson Mac Low’s experimental poetry; during a bustling period, of the magnificent soundtrack—a cut-and-paste audio collage—for the impressive NASA documentary by Francis Thompson, Landing: Apollo 11: Moonwalk One (1969, rereleased in 2009, excerpt included on the Musicworks 134 CD); and eventually of composed music for the soundtrack of Ken Russell’s Altered States (1980).

But one can’t eat praise, applause, and good reviews. So, in the 1970s he drifted into the world of ad jingles, producing, among others, the award-winning “Take the Train to the Plane” jingle promoting the JFK Express, a subway line between Manhattan and JFK airport—even producing a swinging jazz version.

He could have continued churning out jingles and pop earworms but, guided by curiosity, he instead turned to humankind’s relationship to the environment, drifting beyond the world of identifiable song, wandering ever further afield to create organic sounds that communicated with our surroundings, using conch shell, poetry, vocal chants, an Ocarina orchestra, and Dadaistic devices, so that our surroundings, in a Cagean manner, became both composition and composer, and we its musical instruments.

Morrow pursued his fascination with animal languages. Some communicate with spirits, others whisper in horses’ ears. Morrow jammed with toadfish. On August 9, 1974, Morrow and members of the New Wilderness Preservation Band boated out into Little Neck Bay in Queens to perform a concert for—and with—fish, using amplified woodwinds, Moog, fish recordings, and vocals informed by his studies of decoded fish language. He hoped his chants might lead to interspecies communication. “And humour—like the concert for fish—is,” Morrow points out, “a political tool I share with the stand-up guys.”

Morrow as the avant-garde’s Dr. Doolittle? Why not? Like Doolittle, he has talked to the animals—and learned from them: “My Chanting [pamphlet] includes recipes for breath plus voice . . . These include breathing with sleeping people, with animals, and then movement into cross-species communication. I thought I’d cracked the field-peeper and toad-fish languages.”

These quirky works are odes to human diversity, coexistence. His pioneering tactics created an atmosphere that was ever more receptive to the exotic and unconventional. Morrow reached back, way back, to a time prior to music, when humankind was yelping and first exploring its surroundings. Like the Dadaists, he propelled himself into new territory by, ironically, sourcing the ancient roots of communication. The further out his performances sounded, the more rooted they were in investigations of humankind’s deepest roots.

What’s In Is Now Out [or Vice Versa]

Hearing his own voice gave Charlie Morrow an awareness of himself in our strange world. Before God needed to be invented, there were people; before language there was song; and before song there was utterance—vocal chords as the original musical instrument. The Hopi, Popul Vuh, Hindus, Inuits—many of the world’s peoples, in fact—believe our universe was created by a fundamental sound.

Imagine ur-yelps cascading off cliffsides until we hear countless versions of our own voice harmonizing in midair, recreating that first “recorded” instant of sound suspended in mountain air— alley as recording studio; magnetic tape replacing air and memory only, deep into the twentieth century. Or, as Morrow describes it, a “feedback loop of sounding and observing that carries one along,” to usher us into self-awareness

In the 1970s, Morrow drifted from the standard Western canon. Telephone Music is described in his online catalogue and autobiography Years Places Names as “an earsplitting loud tape collage piece that has layered telephone and voice sounds and is built on a series of pressure changing ambiances that crash one into another . . . It was powerful, as my neighbors attested. The subwoofer sound is integral to the piece, which depends on placing [the listener in a bass-heavy sound field and injecting the mid- and high-register] sound layers of the piece above that: a young mezzo soprano singing my original vocalization, telephone line noises, oscillator sounds and choice-recorded ambiances.”

This piece precipitated his chanting works, transforming his own voice into electronically generated sources, in concert, manually processing the chanting to extend his vocal techniques. Chants include Breath Chant (four layers of improvised breath),Evening Star Chant (a multitrack delay-rhythm chant with handheld gong), and Spirit Voices, a shamanic opera based on concepts of Siberian shamanism and abstract vocals that investigated how people around the world greet one another.

Many people cringe upon hearing recordings of their own voices. This is because when you speak, what you hear is not what others hear. A tape of your voice is more like how it actually sounds. This discrepancy is due to the difference between external air-conducted sound through the ear drum and bone-conducted sound through three noise-processing bones of the middle ear. Morrow likes his voice, and loves the microphone.

“My first recordings were on a Tandberg home recorder in my parental home in Passaic. The Tandberg is still in my archive. I did sound poems with the deck. The first one is ‘ELLA’ from my high school years. I’ve always been a sound poet, as much as a composer.”

Chanting both uncouples and binds. Letting go of one realm in favour of another is central to most spiritual quests. Morrow in his Chanting pamphlet describes chanting as “an exploration of the mind and body in connection with the environment and other living species.” These chants attempted to rechannel his birth experiences. “Strong experiences in life work like scarification of the memory ‘skin’ . . . So, I became obsessed with revisiting the prebirth sensibility and made the journey over several years of marking [early life] sign posts—I am sonogenetically driven.”

His “Sky Song” (1977), broadcast on New York radio station WBAI, was synchronized with cloud motions to stimulate the flowing chanted melodies. A second melody was synched with the flights of birds—their paths, speeds—across our visual space. “As birds appear, the singer switches to tremolo across the break, a kind of yodel that has the melodic shape of the birds’ flight paths,” he explains.

Through vision chanting—an important component of his work in the 1980s—he would close his eyes, listen to his breath while channelling the dream world of the unsleeping, observing the visual images in one’s head. This led to an interest in healing, in how medicine people use sound in rituals.

In June 1973, Morrow and Carol Weber celebrated the solstice in Central Park, commencing a long series of annual events that combined “the tribal with the experimental,” including chants like his “Conch Chorus and Bagpipes,” in New York City parks until 1989. The impulse was equal parts curiosity—what is the language we share with nature, the wind, the water, the animals?—and a holistic integration of the self into the flow of nature.

Suddenly it’s summer 2018, and I’m in time-warp America as a throwback earworm emerges from radios everywhere: “Hefty Hefty Hefty! Wimpy Wimpy Wimpy.” The vintage Hefty garbage-bag ads had been relaunched, and you can’t deny the annoying pleasure of this classic jingle. For a month I was telling everyone “I know who came up with that ad—Charlie Morrow.”

The Genius of Fun

“Yes, I am a spiritual anarchist.”

At the 1963 world premiere of Erik Satie’s Vexations, organized by John Cage at Manhattan’s Pocket Theatre, twelve pianists including Cage, David Tudor, and John Cale, played for a total of eighteen hours and forty minutes. At the plink of the last note, someone shouted, “Encore!” That someone was Charlie Morrow, who with a grin quipped: “Some critics have insinuated that I have a sense of humour.”

His 1978 Requiem for George Maciunas called for lawn sprinklers of all sorts to be placed on a large lawn so they could be “performed,” resulting in a symphony of sprinkler iterations. “Exploration and curiosity in my life is driven by communication and social action. I believe in transformation through observation and connection.” His 1962 piece Dance Music for the Blind features dancers carrying soundmakers, such as bells, attached to their bodies “to sketch with in time . . . in the synesthesia of dark dancing with finger motion.” They transmit physical gestures via sound to the audience, which includes blind and blindfolded people and those sitting in complete darkness.

Morrow is also an organizer of instruments, orchestras, collaborations, and events. The open nature of his collaborations are part of his method, but also a necessary crutch that comes with the physical limitations of age, such as bad eyesight: the mind is willing but the body is protesting. “I learned collaboration as a musician. I can be the leader or the last chair trumpet. I wish to play in a band where everyone is better than I am so I can have the bar raised, be challenged. I’m a solitary dreamer who has developed group dream events. I have a broader rather than consistently deep skill set, so I need the best collaborators to do their part. As I produced larger and larger projects, I came up with more skilled, smaller core teams. Efficient planning is key. It distills the vision. That said, I spend most of my creative time in solitude—as a young trumpeter practising and as an elder spider spinning webs. My mother said, ‘Charlie you like to be alone up in your room, knowing there are lots of people in the house.’”

This network approach commenced with New Music for Trumpet (1965) and continues on to this day. “By asking others to energize and support a project through their works, the concept and the project grow, branch out, and [it all] takes on a life of its own. This has social as well as aesthetic benefits in that it builds a community of artists and audiences along the attendant transmission of media.” Which, ironically, means that his limitations create opportunities. “Maybe asthma is my epiphany. Could not escape the wheezes. Trumpet playing was an antidote by building strong lungs.”

“I am inescapably of my species, family, and planet,” Morrow observes. “The perceptual strategies are strangely science and medicine, as well as ceremonial and technologies of the sacred . . . I’m an involuntary weaver-together of extremes in time and place. I’ve been attracted to collaborate and create with like-minded people with strong individual ideas. I was raised by such people, logically directed towards health and community.”

The Multiple Nonredundant

I wondered how Charlie Morrow felt playing an intimate trumpet solo as compared to conducting an entire herd of trumpets as public spectacle. He points out that “the relationship of playing a trumpet solo and being part of an ensemble varies per situation and music. As Jackson Mac Low urges, listening to the others in a group, leaving time for them in your listening, is important . . . there is synchronizing with the beat, playing in tune . . . I have found it useful, as a large-event composer, and fruitful socially to play trumpet in the Bread and Puppet Circus band. In each setting, one listens and plays, knows the score and one’s place, and connects with it all.”

The album Toot! Too culls works from his 1970–2014 “Wave Music” series, which features same-instrument pieces composed for various events including Wave Music for 40 Cellos, Wave Music II for 100 musicians with lights and Native American singer, Wave Music V for Conch Chorus and Bagpipes, among others.

These events fostered a broader role for both classically trained musicians and for audiences by introducing strange noisemakers and altered instruments into informal settings. “But,” as Charlie points out, “in the past, composers did the same, often to get a gig. Mozart wrote many divertimenti, event pieces with odd instrumentation, for the players who were available.”

Business as Unusual

“Insanity as a key word is its own virtue and evil,” Morrow observes. “My business-guy status saved me from a purely out-there status. Not a kook, but a curious cross-genre danger. In commercial music, some said, ‘Don’t trust Morrow; he serves his own agenda.’ In the art world [they said], ‘The guy is commercial, masquerading as an artist.’”

In 1967, he established Charles Morrow Productions, a music and sound-design firm; a not-for-profit affiliate, the New Wilderness Foundation, which included a workshop for experimentation in time-based arts; and the Audiographics label of cassettes of experimental and conceptual works. These endeavours eventually grew to include EAR Magazine, New Wilderness Letter, and the Ear Inn bar, which became a legendary hangout for creatives.

His Charles Morrow Associates handled his commercial sound productions as he turned increasingly to composing and producing. Charles Morrow Productions was established to develop an international network for sound explorations. But with Charlie Morrow Sound, established around 2000, he managed to come full circle, effectively bringing the outside in with his immersive sound design. From the ’70s into the ’90s, he focused on music outside of the concert hall. “I now work to capture and install [outdoor] sound in event spaces, as well as to create spatial sound experiences.”

Because when sound defines a space, that’s ambience. When it defines existence, we call it belief. “For me, music created space in created spaces,” Morrow explains. “My events grow from this vision.” Sound is spatial, architectural; immersive sound allows one to walk through it and fully experience it from inside out, rather than just from the outside in. And sound has obviously defined Morrow’s life.

MorrowSound® provides immersive state-of-the-art sound technologies to create sound that envelops us from all directions, natural sound environments that enhance exhibit experiences so visitors can feel, visualize, and better understand the essence. MorrowSound 3-D immersive sound environments have been installed worldwide at heritage sites, art spaces, museums, hospitals, public spaces, and events, including Moscow’s Jewish Museum, the Louvre, Whitney Museum, Chicago Museum of Science and Industry, New York’s Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, and the 2006 Torino Winter Olympics.

Immersive sound has brought Morrow’s quest full circle. It “has reinforced my vision of sound I first learned in the womb. A fetus experiences the world through the body of its mother, itself a sound-making organism . . . I say that sound artists and designers can now contribute positively to our daily environments.”

Fin[ally]land

Having forsaken New York long ago (“can’t step in the same river twice”), he is now bi-coastal, living and working in Barton, Vermont, along the Canadian border in his farmhouse–archive; and Helsinki, where he lives with Maija-Leena Remes, who he works with on many of his projects. Helsinki is a sympathetic place; he appreciates the Nordic attitude. “Perhaps it is the combination of humour and seriousness of purpose, the depth of the love of nature and the local nature of love [and] a balance of life between personal, family, and work interests.”

I’ve barely touched upon many aspects of his oeuvre because there are, after all, over three thousand items, productions, and events and, in the end, I realize it might lead into the treacherous territory of a full-blown book.

I’ve always been attracted to outsider-underdog artists who combine unlikely genres. I envy musicians. They gather, pull out their instruments and play—things are appreciated, valued, gaps between self and other, between inner and outer are bridged—language is not an issue. I swear if we were to organize a mixed orchestra in Palestine, peace would be within reach.

Charlie Morrow and I are very different, but we immediately found common ground, mutual friends, and shared politics and ideas about creating in this crazy world, discovering that we grew up mere miles from each other in the middle of a defiled land known as Central Jersey.

Michel Foucault’s questions could have been Morrow’s: “What strikes me is the fact that art is something which is specialized or is done by experts who are artists. But couldn’t everyone’s life become a work of art? Why should the lamp or the house be an art object, but not our life?”

Check out iMMERSE! Sound Light Space, Charlie Morrow's podcast exploring the immersive world.

All images courtesy of Charlie Morrow.