“Two musicians, say, coming together to play a piece of music, I think has to be interesting. Even if the results are not in themselves a great piece of music, the way they find to work with each other says something about music. So you can hear one musician figuring out—you can hear it—figuring out how the other musician works, matching what he does against what the other guy does . . . even if it’s not working in complete terms, the process can be, I think, one of the most interesting listening experiences you can get.”

—Derek Bailey (1982)

On a pleasantly warm September afternoon, I am hanging out in a North York park with Michael Lynn, who recites the above quotation (almost verbatim!) from On the Edge: Improvisation in Music (1982), a four-part TV documentary the late British improvising guitarist Derek Bailey wrote and narrated. Perhaps Bailey’s words stuck in his mind because they could be a description of Audiopollination, the improvised music series that celebrated its tenth anniversary in 2022 and which Lynn has been gently steering since the beginning.

No neutral observer, I have attended Audiopollination dozens of times over the past decade. I also played at the series: once with friends on my birthday, and many other times with complete strangers. I have twisted various knobs alongside folks playing piano, saxophone, trombone, and Tibetan singing bowls. Audiopollination is a comfortable place for a relatively inexperienced musician such as me to challenge their limitations. “It’s always been so low-key that people can play quite comfortably there without the stress,” Lynn says. “The crowd is the other musicians. It’s a friendly place where people can just try things.”

Audiopollination has evolved with its community, keeping its core tenet of being a safe space for sonic exploration while also striving to become more inclusive and open to wider circles. It’s a rare situation that is equally welcoming to old hands and new players and agnostic in terms of instrumentation and technique.

“I had an epiphany one day that I needed to start making the kind of music I am making now, so I hosted an impromptu show in my apartment,” visual and sound artist Xuan Ye tells me. “I didn’t know anyone who was in the music communities here. I struggled to find like-minded people. I literally used Google. I remember so clearly. After I typed in ‘experimental music’ and ‘Toronto,’ the sign-up form from Audiopollination came up. So I signed up, using the documentation of that apartment show, and here I am.” Xuan Ye even paid tribute to Audiopollination in a newcomer grant application, writing, “You have no idea how hard it is to get started in a new place. We need more projects like Audiopollination.”

The series has also gathered an extensive archive of audio and visual documentation, which has been a huge resource for other musicians looking for gigs or applying for grants. And the matchmaking format has sparked many lasting projects, such as Kamancello. “The series was a great opportunity to play fully improvised live sets and meet new people in the process,” recalls cellist Raphael Weinroth-Browne, who was new to Toronto when he played his first Audiopollination show in 2014. “It was through this community of improvising musicians that I heard about Shahriyar Jamshidi, a kamanche player who was also relatively new to the city. As an avid fan of the kamanche, and Persian music in general, I reached out to him to see about the possibility of playing together. We met in a classroom at the Glenn Gould School, where I was studying. We improvised for two hours, barely exchanging any words, and then decided to sign up to play at Audiopollination together. This was the first live performance of what would later become Kamancello, marking the beginning of a musical project and friendship that has lasted over eight years.”

Although Audiopollination is largely a hyper-local phenomenon, its roots are in Brisbane, Australia—where Lynn grew up—and specifically in a local music series called Audiopollen held at the back of a fruit market every Saturday. “It was a mix of stuff, a lot of creative music and film and noise together. I was really heavily involved in that,” he recalls. “So when I got [to Toronto], I wanted to do something similar.”

Lynn became involved with Somewhere There, a Toronto artist-run creative music presenter. “They had the improvisation stuff covered for sure, but I wanted to have more people playing in two hours.” Lynn was a fan of Coexisdance, the monthly series of movement and sound improvisation that his friend Colin Anthony founded in 2006. “I wanted that setup, which was shorter sets and more people involved.” The first shows happened at Somewhere There’s Sterling Road venue, but eventually Audiopollination settled in at Array Space, where it was a tenant and is now an official series.

With its local word-of-mouth network and regular access to an established space, the series soon became a stopping point for visiting improvisers from across Canada and several other continents, who would usually play alongside the series’ regular mix of locals. Alister Spence, Sandy Ewen, Peter Prescott, Satoko Fujii, and Michael Fischer are among those who have landed at Audiopollination.

In 2015 the series introduced what has become one of its defining features when a sign-up sheet appeared in a shared Google document. “I had issues with me curating it all,” Lynn says. “I can only invite who I know. I wanted to make it more democratic.

“The sign-up sheet allows those situations to happen for people who have never met each other. They’ve got twenty minutes, but within that twenty minutes they’re working out what to do and how to develop, and I like that part of it, too.”

Switching to this self-curation model also led to more reflection and analysis. “I quickly realized with the sign-up sheet that I was still having bias about who was signing up,” Lynn continues. “If I look through my Facebook, a main way of approaching people, I see that I have a heavy bias toward white cis males. But also, I think, white cis males will sign up first, and it might be a longer process for others to do so.”

It didn’t take long for the situation to adjust, with the sign-up sheet gaining an extra column to ensure there was space in each set to include and embrace performers from a wider range of identities. “I had a problem that [the series] was being completely dominated my me, a white cis male, and I was making the choices. So that’s why I put in that extra column. The language is expanding, and as the language expands I try to expand with it.” Currently, the Audiopollination sign-up sheet reserves space for performers who identify as any of the following: BIPOC, LGBTQ2S+, disabled (visible or invisible), female, agender, genderqueer, or gender-fluid.

That built-in inclusiveness has been a key part of the series’ influence spreading farther afield. In April 2022, improvising musician Emjay Wright began putting together Audiopollination Guelph, presented in partnership with the Guelph Jazz Festival. “Back in 2017, I remember being amazed by the immense talent of the people I shared the bill with at Audiopollination, and how welcoming Mike and the community were to new improvisers and those without any formal musical training. The utter lack of gatekeeping—while simultaneously cultivating some extremely powerful music—was really inspiring,” says Wright in an e-mail conversation. “It’s almost like traditional gatekeeping practices are rooted in oppressive and elitist ideology, and not actually intended to better the art world.

“I moved to Guelph in 2021, knowing there was a great passion for improvisation in the city. Audiopollination was incredibly important to my development as a musician, as an improviser, and as a person in general, so I wanted to share it with my new community, which seemed to need community spaces in a post-COVID world. After having great success with my Toronto-based show series ponyHAUS, I felt confident that I would be well-suited to coordinate and host this event. Mike was kind enough to allow me to use the structure and the name. I think that has led to a great deal of interest in the improvising community of Guelph.

“Because I am a queer non-binary person, one new aspect of the series is an audience made up of many young queer people like myself. I’m promoting the event to these folks as well as to the improvising community in Guelph. [There is] lots of overlap in those two demographics, and hopefully, through the show, the overlap is becoming larger. Due to my position as a young developing musician, I am very vocal about the show being an open space for young artists, autodidacts, and first-time improvisers. This is not to say that the original Audiopollination is not a space for those individuals, just that I am intentional with how I position the show and how broadly I invite artists and audiences.”

This dynamic is similar to what Michael Lynn is working toward, as Audiopollination enters its second decade. “The series is a good means to explore things about identity. When there are more new people coming in, it forms a more diverse community,” he says. “It really challenges ideas about normativity, of what an instrument can do, of what music is.”

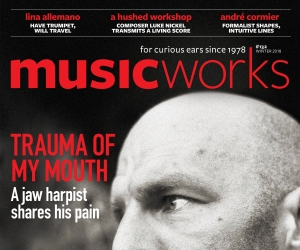

ALL AUDIOPOLLINATION PHOTOS BY JOE STRUTT, TAKEN AT ARRAY SPACE

Top: Audiopollination founder and musician Michael Lynn

Middle: Kamancello (Raphael Weinroth-Browne, Shahriyar Jamshidi)

Bottom: Isabell Clermont, Michael Lynn, bea Labikova

LINK: <audiopollination.ca>