November, some might say, is not the ideal time to visit the wild West Coast. The days are short, the leaves are down. In any normal year, monsoon season will have kicked in, producing alternating bands of drizzle and downpour, both equally grey and almost equally wet. But when the International Society for Contemporary Music convened its World New Music Days conference in Vancouver in early November, attendees—and the general public as well—had a chance to slip out of their anoraks and into a midsummer idyll, thanks to a new multimedia installation by Julie Andreyev and Simon Lysander Overstall.

Biophilia is part of the creative partners’ ongoing investigation of the interface between human constructs and animal creativity. Audiences “enter” Denman Island’s Fillongley Park, a forest thick with Douglas fir and red cedar on the shores of Lambert Channel, the Salish Sea passage that separates Denman from its eastern neighbour, Hornby.

Through audio and video recordings made in July 2017, Andreyev and Overstall introduce visitors to the residents of this twenty-six-hectare refuge: the ravens, robins, amphibians, and insects that call it home, alongside the waves that beat on its shores and the winds that rustle its leaves. These are reproduced via quadrophonic sound, and depicted on a HoloPro screen hung down the middle of the Western Front arts centre’s venerable performance space, the Lux.

But theirs is no simple documentary project: through Overstall’s generative software and use of granular synthesis, these recordings will be given a subtle digital shimmer, to better convey the elongations and relaxations of time that occur in a natural setting. Meanwhile, Andreyev will play call-and-response with the birds and the bees and the winds, using a theremin in concert with their vocalizations.

Overstall explained, in a conference call with Andreyev held a couple of months before the premiere of their new work: “The way we’re imagining it right now is that there’s layers, like a pad underneath which may be processed sound, and then some background sounds from the forest that are less processed but recombinant, in that different moments are played back at different speeds. And another component, then, is the theremin—the human response in the installation.”

“I wouldn’t say I’m a musician,” adds Andreyev, an associate professor of New Media + Sound Arts at the Emily Carr University of Art and Design, “but the theremin offers a way to make various sounds without having to enter into the business of music. So what we’ll do in the final production stage of the project is play some of the finessed recordings of the birds, and then I’ll respond on the theremin, using methods like biomimicry—listening and seeing if I can communicate back, in a sense.”

The idea, she says further, is to help viewers and listeners realize that even humans are part of this ecosystem—or part of the biophony, to use a term Andreyev ascribes to electronic-music pioneer and field-recording guru Bernie Krause.

“What we’re maybe trying to achieve is a way to enter into listening in a different way,” she says. “So it’s not through what we know, but through different ways of knowing.”

And what better way to discover this than in a forest at dawn—or with a digitally augmented simulacrum of one?

SUBSCRIBE to Musicworks NOW and start with the WINTER 2017 issue and companion CD, including a sound excerpt from Biophilia.

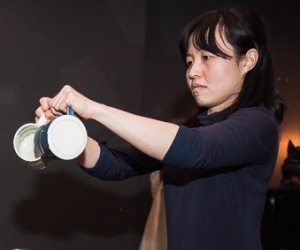

Top photo: Still from the making of Biophilia, courtesy of the artists.