“I’ve always been a fan of silence. So, when I lost the ability to, you know, experience silence, I started looking at noise as a form of quiet in times when I needed some mental clarity,” reflects multidisciplinary artist Seth A Smith via email. Since 2019, he’s been living with tinnitus. Developed after years of playing in loud bands—like Burdocks and Dog Day—throughout the aughts and made permanent following a severe ear infection, the perpetual noise in his right ear is “high-pitched ringing, chirping like a smoke detector or a sea of crickets.” In Constant Interruption, his recent sound project, Smith blends instrument-building, installation, performance, and recording as a way of creating terms of consonance with the ever-present sea of crickets.

At the onset of his condition, Smith felt perpetually irritable, distracted, and unable to concentrate. After several years of self-directed research and experimentation, he found that nothing short of a fundamental change in outlook would allow him to live with, rather than suffer from, the high-pitched ringing. Following that mental shift, Smith settled into sound masking—the practice of shifting one’s awareness of the intrusive sound by adding complementary noise—as a therapeutic approach that brought respite by restoring some of his stability and focus. In the spring of 2022, supported by a grant from the Canada Council for the Arts, he began designing and building acoustic instruments in the hope of unlocking more profound relief.

Smith, who is also a filmmaker, developed an interest in building instruments when he started scoring his films. Over the past decade, his focus has shifted from performing as a guitarist and vocalist to directing and composing the scores for what he describes as “elevated horror.” His three features explore complex themes through a mix of eerie psychosocial plots, heady natural and not-so-natural imagery, and curious bodily gestures—all tinged with a sui generis sense of psychedelic noir. Unsettling sounds and spectral scores feature prominently: Lowlife (2012) is a drone-based swampsploitation story about a starfish-huffing artist’s descent into oblivion; The Crescent (2017) is a liminal suspense film following a young widow through the furies of grief and the fog of a coastal shoreline, underpinned by Smith’s brooding Italo-industrial music; Tin Can (2022) is a timely, claustrophobic sci-fi film focusing on the dystopic aftermath of a plague propelled by pulsating noise, a discomforting score, and a few harpsichord sonatas from eighteenth-century Italian composer Domenico Scarlatti added for good measure.

The sounds Smith has created for Constant Interruption are certainly less anxiogenic, but not entirely so. “Tinnitus is a very emotionally charged thing,” he explains. “It’s a feedback loop between the phantom sound and your feelings toward it. My initial aim was to inject a positive mood in the music for a calming effect. But as I made it, seeking sounds that emulated my experience, the tone started to match that anxiety of tinnitus.”

The instruments he built for the project are generally based on metal: large coils, steel rods and string, cymbals, and sheet metal resonators. Smith, who is based in Nova Scotia, cites his father’s work as a blacksmith as a source of guidance and inspiration, as well as the work of John Little, a local metalworker his family spent time with when he was young. Little’s 2001 recording Iron Sky features ten improvised movements wherein the late free-jazz drummer Jerry Granelli activates Little’s beautiful abstract sound sculptures through extended percussive techniques, with accompaniment from bass clarinetist Jeff Reilly. On his website, Reilly references the unique nature of the materials at play on the album and the “joy in making sounds that have never been heard before.” And while outright joy may not be an express goal of Smith’s project, the search for novel sonic qualities is at its root.

The idiosyncratic nature of Constant Interruption, which was released as a digital album in August 2022 through Smith’s own Fundog label, is typified by a set of wind-activated bells that Smith created and dubbed his “melted car chimes.” When asked about the name, Smith elucidates a typically singular source of origin. “I live in a remote area outside of town, and every so often joyriders will set cars on fire on a hill near my house. Over the years I've collected some of the melted aluminum remains—from the radiators, I'm guessing. I had been wondering what to do with them, and finally decided on using them in a wind chime, along with some copper and aluminum pipe. I like them. The pieces are heavy enough that they’re not clanking all the time. They need a good breeze.”

This rugged, isolated context is a major factor in Smith’s work. In Nova Scotia, a largely rural and underserved part of the country, there’s a tangible lack of higher-level investment and interest in contemporary, forward-thinking art. So, like many artists in the region who are working on the fringes and facing economic hurdles and a void of institutional supports, Smith has sought refuge in the rural experience. In 2010, after living and working in Halifax for over a decade, he and his family relocated to West Pennant, a former fishing village dominated by rocky outcrops, foggy beaches, and forested areas. Beyond simply sourcing materials for his instruments in the surrounding environs, Smith also installed the instruments in the wooded areas surrounding his house, inviting the elements into his process. “I was looking for trees that were strong enough to fix all the metal components to, but also ones I could manipulate or sway while playing,” he explains. “Sometimes it was places where the wind or rain could have some influence. There was one with a little cave chamber in it that had a neat resonance. They’ve become kind of sacred to me now.”

This engagement with the natural world is highlighted by Weather Mask, a companion piece to Constant Interruption that was released in November 2022. The album leans further into the concept of nature as a source of healing, featuring fourteen field recordings of naturally occurring noises—wind, water, and ice–that Smith sourced in and around West Pennant. “When I first got tinnitus, my [otolaryngologist] said, ‘Oh, you live in the country, that’s too bad. It’s so quiet there,’” Smith recalls, adding, “It’s not as noisy as the city, but nature can be a great noise-masker too.”

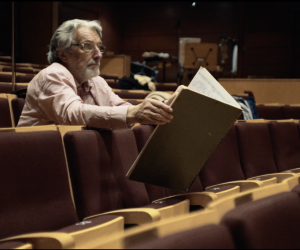

The best way to experience Smith’s recent work is to watch him creating and capturing sounds in the wilderness. The video documentation for Constant Interruption, which can be found on his YouTube channel, shows the artist performing on his instruments installed in the wild: surrounded by spruce trees, low to the ground, crouched forward amid boulders, long, dark hair draping out of his hood, stuffing a microphone between tree roots, bowing or twanging on coils, swaying to the internal rhythms of perception.

“I had one very moving experience when playing the firbass [made of a balsam fir tree stalk, a cello string, a large coil spring, and a hammered steel sheet]. There were some bird calls from the woods, then a huge flock of yellow birds landed on the surrounding trees and boulder where I was playing. They watched and tweeted along for about a minute, then flew off. It actually made me tear up a bit,” he reflects.

“There was also a time when I think I might have been in a ‘Duelling Banjos’ scenario with a neighbour’s chainsaw.”

Smith’s compositions are nothing like the rollicking folk music featured in Deliverance, but his reference to the film’s iconic musical moment does speak to the eerie presence and absence in Constant Interruption. In theory, the drone-based compositions that comprise the project are an accompaniment to a sound that exists exclusively in the composer’s ear. As Smith points out in a description of the associated album released on Bandcamp, the creative process was a form of sound therapy for him, but the album is “designed to give temporary relief to those suffering from tinnitus, using a wide frequency range to activate the entire hearing palate.” In this sense, the project is an experiment in empathy: How can one come to understand acutely the unique condition of another? And is it possible to use art to move through the subjective and address the collective experience?

Smith understands his case of tinnitus to be relatively mild on the spectrum: “Many have it worse than I do, especially older folks, veterans. A friend of mine describes his [tinnitus] as the volume and sound of a train.” But the challenges associated with tinnitus aren’t simply a matter of volume, he points out. “The invisible aspect is a bit alienating. Talking about it—it’s almost like you’re telling someone about a bad dream you had. It’s kind of hard to understand for people who don’t experience it. But a lot of people out there do have it, more than you think.”

PHOTOS BY SETH A SMITH

FYI: In 2023, Seth A Smith is working on a new recording from his side project Dog Day.