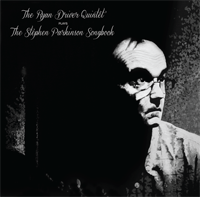

Since 1999, the Ryan Driver Quintet (as well as his Sextet and Quartet) has been serving up a unique, cooked take on jazz balladry—especially at its monthly residency at Toronto’s Tranzac venue. Ryan Driver Quintet Plays the Stephen Parkinson Songbook, its first studio recording, could gain the quintet a more international recognition, with the vinyl version released on U.K. imprint Tin Angel.

Each song the band performs is framed by Driver’s suitably unassuming croon and exudes the usual emotional profile of jazz balladry—nocturnal coziness, nostalgia, inebriation by love or by booze—but beneath the surface the ensemble is always chiselling away at the ostensible logic of the music. Their skeins of sweet, candlelit notes melt together, suspending and evading coherence just long enough for them to ooze back to the recapitulation of the head. Then when Driver starts singing, it makes enough sense again for you to recognize that the song has come full circle. The quintet comprises some of Toronto’s best improvisers. Although the format of the music necessitates a degree of restraint, the work is as much about the songs as it is about showcasing spontaneous interplay. As the pieces open up, each instrumentalist becomes equal in the sonic picture, relishing the small surprises they discover within the romantic frameworks.

Nick Fraser (drums) and Rob Clutton (bass) are natural personnel choices. On top of being incredibly open free improvisers, both are adept at finding creative ways through more straight jazz expressions. It’s tempting to frame Martin Arnold as the wild card; his guitar is always reedily overdriven and capoed in an open tuning, ornamented with copious deep swoops—either whammy bar, whammy pedal, or wah-wah—and provides a chatty running commentary. Yet, though his contributions are steadfastly odd, he never fulfills the stereotypical role of the disruptive volatile guitarist (think Arto Lindsay panic attacks in Lounge Lizards). While always present, he’s just underpainting each song with other melodic perspectives. Brodie West (alto saxophone) is perfectly at home here, his quirky out-of-breath lyricism relaying musical information between Arnold’s guitar and Driver’s voice. Driver’s piano- and celeste-playing are at once detailed and vague, variously sketching outlines of chords, querying the musical texture, giddily twirling through a cascade of notes, or whispering some form of sweet nothing.

Toronto composer Stephen Parkinson is known primarily for his imaginative, gently eccentric chamber music, but he has crafted a set of extremely successful ballads for this recording. His compositional recipe—the tried and tested formula of evocative imagery, humour, clever bendings of lyrical cliché, sweet tuneful phrases, and the requisite degree of permeability to interpretation—reminds listeners exactly why ironic sendups of this genre always fall flat. There’s as much room in this music to laugh at oneself as there is to cry. In fact, they may even happen at the same time.

Over the years, Driver and company have been teasing out all the nuances of this medium; their free-form take on it encompasses it all—and all at once—making for disorientingly sentimental music that is knowing, but never arch.