There has been a flurry of activity around Pauline Oliveros’ work this year. The eightieth birthday of this music pioneer has been marked with celebratory releases, most notably by the aptly named Important Records. This label has now documented her very first and her most recent offerings. Reverberations: Tape & Electronic Music 1961–1970 is a compilation of Oliveros’ early electroacoustic pieces in a twelve-disc box set. It covers the years during which she worked and recorded in various Californian studios, among them the Tape Music Center in San Francisco, relocated later to Mills College in Oakland and renamed the Center for Contemporary Music, with Oliveros as its first director; and also in the University of Toronto Electronic Music Studio. The most recent recordings here reviewed document a week-long residency of her Deep Listening Band at Town Hall Seattle in January 2011.

Although several decades separate these recordings, and although the sounds produced differ widely on either side of that time span, they all demonstrate that Oliveros’ inquisitively creative mind has been at work all along. The music is all about improvisation, in which electronics play an important role. At the core of this work lies an attitude of intense listening. As Oliveros has often stated, her interest in listening stems from the moment when, hearing her first performance on tape, she discovered how much she had missed sonically of what had actually been happening around her. This led to an approach of concentrated awareness called deep listening that became the foundation of all her activities. Central to this concept is the conscious use of hearing—instead of sight—as the predominant sense in assessing and dealing with the world around us, thereby flying in the face of ingrained and unquestioned habit. In her Sounding the Margins—a collection of writings from 1992 to 2009—she makes a case for using terms derived from auditory rather than visual fields of experience to describe sonic events.

Oliveros used the deep listening approach in composing the pieces documented in Reverberations. What is more, it is directly connected with a desire to explore and—quite unique in electronic music at the time—to improvise. Time Perspectives, her very first tape piece, was built with sounds from objects she found at home, such as cardboard tubes, modified through lo-fi means. Later pieces were constructed with sounds and pitches she created through a signal processing technique called heterodyning, in which two tones—in this case, from sine wave generators that produced tones pitched above the human hearing range—are combined together in real time to create a third tone within hearing range. The resulting music bears all the hallmarks of improvisation, as Oliveros responds to what unfolds before her ears. You can follow how she adjusts pitch and timbre, how split-second decisions make her change her course. Her approach doesn’t result in smoothness of tone but it’s a thrilling experience to follow along with the twists and turns. Regardless of whether it’s in one of her “Bog” pieces, inspired by pond creatures, or one of the pieces in which she uses Muzak recordings as a ground layer for painting her own sounds with vigorous strokes and sweeps, her decisions (and the titles she thinks up, such as Mewsack for one of the latter works) betray an open and playful spirit. About half of the music in Reverberations was recorded at the state-of-the-art University of Toronto Electronic Music Studio, where she studied with Hugh LeCaine for some months in 1966 to prepare for her position at Mills, evidently a hugely inspiring period.

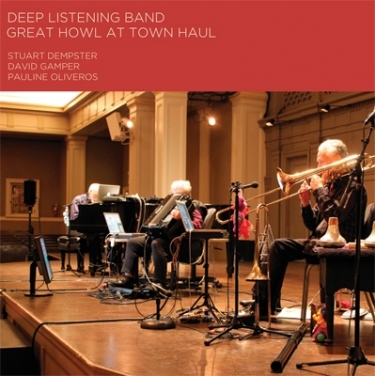

Oliveros continued to explore improvisation in her Deep Listening Band, established in 1988, and in pieces such as Primordial / Lift (1998). In 2011 the Deep Listening Band—Oliveros, David Gamper, (who sadly passed away later that year), and Stuart Dempster—held a residency at Town Hall Seattle. The week, which was spent exploring the space through improvisation and culminated in a concert, proved extraordinarily fruitful, yielding a harvest of two double LPs and one CD of delicate and in-depth collaborative improvisation. In conjunction with the acoustics of the hall, recording engineer Michael McCrea constituted a fourth musician. These recordings emphasize that space has always been a central issue in Oliveros’ music. The musicians of the Deep Listening Band only gauged the rich complexity of layerings and mixtures created in the hall to its fullest extent on hearing recordings afterwards—a curious but powerful echo of Oliveros’ early experiences with listening.

Likewise, listening to all these releases is best done over loudspeakers. The placement and movement of the sounds relative to each other, the way they fill the room and project reverberations into and around it, can’t very well be appreciated when headphones pump the sounds directly onto the eardrums. It is recommended to allow the body its share of resonance.